We know readers tend to be writers too, so twice a month, we’ll feature writing tips from our authors. Who better to offer advice, insight, and inspiration than the authors you admire? They’ll answer several questions about their work, share their go-to techniques and more. Now, get writing!

What writing techniques have you found most important or memorable?

Probably “Outline, Cross Fingers, Stress-Eat Thai Food.” It’s my own invention. Basically you just try to create a loose structure for your story, essay, or book and then hope for the best as you eat—past the point of satiation, this is

crucial—directly from plastic delivery containers.

How would you recommend creating and getting to know your characters?

I think it’s hard to create a great character in a very calculated way, like in “Weird Science” when Anthony Michael Hall and Ilan Mitchell-Smith enter all of their specifications into their ancient computer and then Kelly LeBrock manifests in a turtleneck crop-top. In my experience, characters start out fuzzy and one-dimensional, and then you have to sort of coax them into focus.

Often I’ll get the germ of an idea from something I hear on a podcast, or someone I see on the subway (pro tip: the New York City subway, in addition to being a magical underworld of many nefarious smells and diverse crazy people, is basically a free vault of endless characters!). My high school art teacher once asked my class to sketch the shoes of a stranger we saw on the street and then make up a story about where they were going, and that’s a pretty good metaphor for what I do when I’m writing fiction. I’ll start with some detail, like shoes or an expression or a quirky personality trait, and then build from there.

In terms of getting to know them, you can do a lot of prep work if you want (for example, one playwriting book I read—and by way of disclaimer I am not a playwright, so clearly I missed the point—suggested interviewing each character, on paper, in their own voice, about his or her life story before beginning), but I think it’s OK to start without it. The detail work—what makes each character interesting and idiosyncratic—often happens for me as I’m writing.

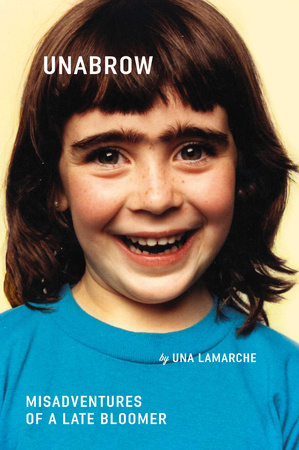

However, it bears mentioning that in my nonfiction essay collection

Unabrow, I

am my own main character, so to get to know

her I actually lived inside my body, endlessly picking apart my every waking thought twenty-four hours a day for 34 years. It’s very Daniel Day-Lewis and not for the faint of heart.

After developing an idea, what is the first action you take when beginning to write?

If there is anything in my life that I can turn into a list or outline, I will do it. It is a fact that I once TO DO-ed my shower regimen (wash face; shampoo; rinse; body wash; rinse; condition; shave legs; rinse conditioner; stop being such a sociopath; towel dry), so it follows that I like to summarize and outline my work to within an inch of its life. Usually I’ll start by writing a one-page summary of the idea and then developing that into a longer outline. With

Unabrow, since it’s comprised of 20 shorter essays, I made a big chart on two pieces of poster board with boxes for each essay and the life event or theme it would tackle. Then I covered it in color-coded Post-Its and impulsive scrawls of illegible handwriting so that the finished product looked like something a serial killer might make after finally reading through her backlog of

Real Simple magazines.

Is there something you do to get into a writing mood? Somewhere you go or something you do to get thinking?

I have to trick myself into getting inspired, since actively trying to think of what to write about tends to make my brain short-circuit, open up a Netflix window, and stream old episodes of 90s sitcoms until the thinking subsides. Just taking a walk and running some errands usually helps, the more boring the better. The only downside to this practice is that I tend to like to talk out loud to myself when I’m generating ideas, so I look insane. About half the time I realize, much too late, that I can use my cell phone as a cover.

Did you always want to write? How did you start your career as an author?

I have this file my parents collected for me of a bunch of stories and poems I did starting around age six and going through high school. They’re almost all either insanely short or unfinished, and largely terrible, but they were clearly labors of love. So I like to believe that I was always a writer in my soul of souls, but was just scared to try to do it in any serious way until my late twenties.

I remember not wanting to major in English in college because

so many people majored in English—I tried to play it like it was such a cliché, but really I think I was afraid of the competition. So instead, I majored in film studies, because I liked movies. Then, because at the time I was under the incredibly misguided impression that your undergraduate liberal arts major should determine what you do with your entire life, I started working in film—mostly doing archival research for the kinds of documentary television specials that involve slo-mo reenactments of people riding horses and brandishing muskets. While I was doing that I started a blog, which became, almost a decade later, the springboard for

Unabrow.

But, if I’m being honest, the main reason I’m writing professionally right now is that I got unceremoniously fired from my job in 2006. I was just sort of blindly continuing on a path I didn’t really like—archival research was neither my strength nor my jam—but I never would have quit, so really I’m lucky that I sucked enough to warrant getting the boot. After that, I made a conscious decision to try to become a writer. What that meant to me, at the time, was applying for an office manager job at a magazine, ingratiating myself with the editorial staff, and then pestering them with my writing until they published something (for free, of course). Amazingly, it worked. I moved up from office manager to managing editor and bounced around New York-based magazines and newspapers writing celebrity profiles and pithy headlines about purses until 2011, when I went on maternity leave. After I realized how little I made as an editor and how much full-time childcare would cost, I decided to try to freelance and stay home with my kid.

I can’t in good conscience recommend this as a general strategy, but for

me, becoming broke and desperate while simultaneously completely sleep-deprived led me to take risks that I would never previously have dared. On the suggestion of a friend who worked in publishing, I decided to try my hand at young adult novels, which resulted in a two-book deal with Razorbill (

Five Summers, 2013;

Like No Other, 2014). Then, in the frigid winter of 2012, I auditioned for a live reading in New York called Listen to Your Mother. I got in, performed an original comic piece on all of the mistakes I had made that I wanted my future children to avoid, and received an email the next day from Brettne Bloom—now my amazing literary agent—who had been in the audience and who would go on to shepherd

Unabrow to a sale at auction in the summer of 2013.

Either Seneca the Younger or Oprah Winfrey (you’re no help, Google) said, “luck is when preparedness meets opportunity,” but I think my story proves that luck can also be made from a murky mixture of professional misjudgments, procrastination, hope, fear, and many,

many hours of television.

What’s the best piece of advice you have received?

Once, during a film class in college, my brilliant professor Jeanine Basinger said that all movies share the same dozen or so plots when you get down to it, and that what makes a story really unique is how the filmmaker tells it. I have applied this to writing and taken it to mean that coming up with a story that no one else has ever thought of before (“

Twilight, but with centaurs! And one of them has MS!”) is near-impossible, but that it doesn’t matter. The thing that will make your story one of a kind is your voice. If your dream is to create the next insane dystopian franchise, have at it. But if it’s not, don’t be afraid that your story’s already out there; it

can’t be. No one can tell it the way you can.

What clichés or bad habits would you tell aspiring writers to avoid? Do you still experience them yourself?

My downfall will be my ability to procrastinate and avoid writing. I do it so much that I had to install software on my computer to block the Internet and shame me when I inevitably attempt to check email or Twitter every nine to eleven seconds. I don’t believe you have to write every day, or at a set time for a set duration, to be a good and successful writer, but I do think you have to muster enough willpower to do it at least a few times a week in a focused way.

In terms of clichés and bad habits in the writing itself, it’s hard to give specific examples. Sometimes clichés work, and one person’s bad habit is someone else’s favorite thing. But here are a few things I do that I’m trying to stop doing:

- Sticking unnecessary adverbs in after lines of dialogue. Like, “I don’t seem to trust my readers to infer tone from what’s being said,” she said worriedly.

- I like to cram as many words/jokes into a sentence as humanly possible—often including asides within dashes (or parentheses!)—and while my aim is to amp up the humor with verbosity, I realize that it often has the opposite effect. If a line is poignant or funny, it’ll usually have more impact if it’s pared down to its most essential words.

- Having characters live too much in their own heads. It’s always better to show how someone feels through action and dialogue than to tell it to readers directly through the person’s inner monologue.

- Dropping too many pop culture references that will date the writing. I live for pop culture. I love it. It’s an essential part of who I am and how I see the world. But as fun as it is to weave current events into fictional scenes, remember that (hopefully) your book will still be kicking around decades from now, and that it will interrupt the narrative flow for our future cyborg relatives to have to pause to do a GoogleBrain™ scan for “Kimye.”

Describe your writing style in 5 words or less.

Clever conversation with tipsy friend.

Do you ever base characters off people you know? Why or why not?

I don’t base an entire character’s personality on anyone specific, but I absolutely borrow traits and quirks. Part of it is just that it makes developing characters easier if you can pick details out of real life experience, but also I love leaving Easter eggs for my family and friends to recognize. I’ll only use something if it’s flattering or if it’s funny enough that it won’t be taken seriously (for example, a good friend of mine is really into Eastern medicine—specifically colonic therapy—and so I had a camper in

Five Summers with her same first name reading a book about it. She took it in stride.)

Obviously in my nonfiction I write about my husband, my parents, and other assorted real people whom I love and don’t want to hate and/or divorce me, so I tread very carefully with how I depict them. I’m willing to poke fun at some of their personality traits, but again, only if I’m reasonably sure they won’t be offended. Even just describing someone I know in real life can be frightening, because what if they read it and think, “Is

that how she sees me?” I keep telling my friends that there’s almost nothing about them in

Unabrow but that it’s because I love them too much to risk it. (For the record, I love my husband, my parents, and my sister, too, but since they’re the closest people to me in the world they’ve already accepted that there’s no escape. Sad trombone for them.)

Read more about

Una LaMarche‘s book,

Unabrow, here.