But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

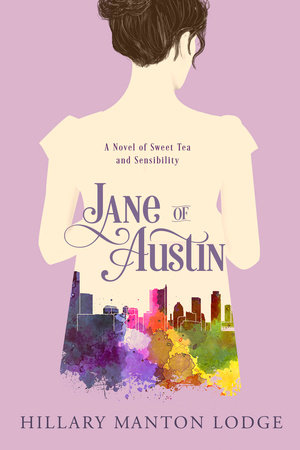

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

Hillary Manton Lodge on Jane Austen’s enduring appeal

Hillary Manton Lodge is the author of the critically acclaimed Two Blue Doors series and the Plain and Simple duet. Jane of Austin is her sixth novel. In her free time, she enjoys experimenting in the kitchen, graphic design, and finding new walking trails. She resides outside of Memphis, Tennessee with her husband and two pups. She can be found online at www.hillarymantonlodge.com.

My grandmother read everything. Books about travel, antiques, architecture, mushrooms. She read murder mysteries by the stack until my grandfather passed; afterwards, her tastes veered into sweet romances, narrow paperbacks with titles like The Sophisticated Urchin and Destiny is a Flower.

But she loved the classics best, Jane Austen most of all. When I was nine, she gave me a battered paperback Penguin Classics copy of Pride & Prejudice. I didn’t make much progress with at the time – I was an advanced reader, but not that advanced – so my first experiences of Austen were in film. First, with the 1940 Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier version, and later with the 1995 Andrew Davies mini-series for the BBC.

When the latter aired on Masterpiece Theater, I visited my grandparents’ home every Sunday night for six weeks while we watched Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth argue and make eyes at each other. My grandfather made us an English dinner – or rather, his interpretation of one – and asked if they were “dahn-cing yet?” As a twelve-year-old with two younger siblings, the dedicated time with my grandparents felt special and grown-up.

But it wasn’t until I was an adult that I was able to read and appreciate Austen’s work. As a high-schooler, the subtext of Emma flew right over my head. But as an adult – and author – I was able to see the work, craft, and wicked humor just beneath the surface. I made my way with pleasure through Pride & Prejudice, Persuasion, Sense & Sensibility, and Emma – Mansfield Park and Northanger Abbey are next on the list.

I read them in time to talk to my grandmother about the text; she passed away at the age of 100, and by then the one-two punch of dementia and hearing loss had made it difficult to converse on a specific topic for any length of time. But we were able to compare notes, and we shook our heads over what a pill Darcy could be.

A deep dive into Austen for Jane of Austin, then, felt natural. My editor gave me the title and free reign over it, and after a little consideration I reached for Sense & Sensibility – after all, my last four books had featured self-contained women who navigated the world while keeping it arm’s length. Who better to buck that trend than a character modeled after Marianne Dashwood?

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here:

But updating a novel set during the early 19th Century has its challenges. For starters, there’s the teeny fact that women can not only inherit both property and money, but can have jobs without being cast out of polite society. When necessary, I borrowed from other Austen novels, and gave my version of Marianne – Jane, in my own novel – depth that would have eluded the original 17-year-old character.

There were challenges, but also pleasures. And it’s the pleasures that are why we revisit Austen’s work so often. Her books are populated with people we know. I’ve met Fanny Dashwoods and Mr. Eltons and Mary Musgroves – we all have. Her stories resonate because they’re inhabited by our own neighbors, parents, and co-workers.

But the familiarity of Austen’s literary world should never be mistaken for simplicity. As I wrote Jane of Austin, I got stuck. A lot. And when I did, I returned to the text. Every time, there was something there. Whether it was a witty line or an insightful scene, I always found something to springboard off of and keep the story rolling.

And that’s the beauty of Austen’s work. There’s always something there. There’s wit and romance on the surface. For the deep thinker, there’s sharp social commentary and character study. And no matter the novel, there’s the pleasure in knowing that there will always, somewhere, be dancing.

Learn about the book here: