This article was written by Jayne Ann Krentz and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

This article was written by Jayne Ann Krentz and originally appeared on Signature Reads.

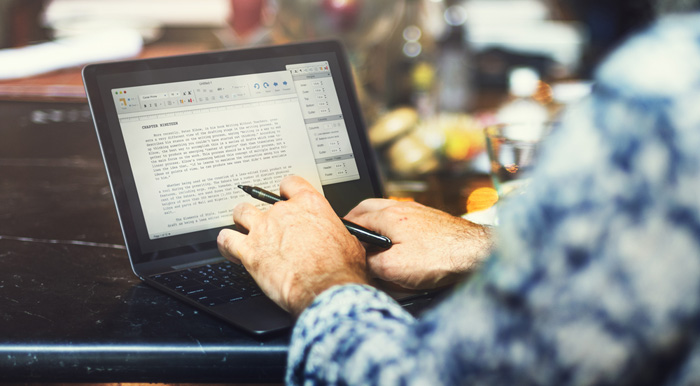

Give the same plot to ten different writers and you will get ten very different stories. No two will sound alike. Why? Because every author brings a unique voice to the craft of writing. Voice is everything when it comes to telling a story.

It isn’t clever plot twists or deep character insights or detailed descriptions that draw a reader back again and again to a particular writer — it’s the writer’s voice. Just to make things even more complicated, the truth is that no two people respond to a writer’s voice in exactly the same way. Some readers will never be compelled by your voice. With luck, others will fall in love with it. Voice is hard to define because it’s a mix of so many things — your core values, your world view, your personality, your sense of optimism or cynicism or despair or anger or bitterness or hope — all those things are bound up in your storytelling voice. And then there’s the craft aspect. You can write successfully for your entire career without giving a moment’s thought to your voice. But just as knowing and understanding your core story can be extremely useful at various points in your career, so, too, is having a clear sense of your voice. If you comprehend its strengths and weaknesses, you will be able to figure out how to sharpen it and make it more powerful. How do you identify your writing voice? Here’s a simple exercise: Write a scene from start to finish. It should be a scene that is infused with the emotions, themes, or conflicts that compel you as a writer. It is helpful to think of scenes as short stories. They have a beginning that engages the reader, a middle in which emotional and often physical action takes place, and an endpoint that either resolves the narrative or provides a cliffhanger that leads into the next scene. Give your scene to a couple of people to read. These should be people you trust. Make it clear that you do not want a writing critique. You are not interested in their opinion of your characters or your plot. You want one response, and one only, to the following question: “What is your emotional takeaway from that scene?” Did you make your reader’s pulse kick up? Did you arouse curiosity? Anger? Sympathy? Did you scare your reader? Did you make that reader want to know what happens next? Your goal is to identify the single strongest emotion that the reader experienced while reading your scene. That response will help you analyze the strengths and weaknesses of your voice. The worst possible reaction from a reader is no emotional reaction at all. There is nothing that will kill a writing career faster than storytelling that bores the reader. Put the most engaging elements of your voice on display in the very first sentence of your book. Readers will not give you a few pages or a couple of chapters to get the story going. You must draw the reader into your world from the very first sentence, and you do that with your voice. Listen to your writing voice. It will tell you what kinds of stories you will write with the most power. Once you have figured out your voice, do everything you can to strengthen it and make it more compelling. Voice is your superpower. Discover it. Photo by Elijah O’Donnell on Unsplash