Author Q&A

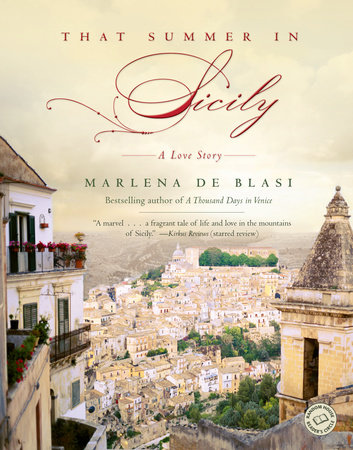

A Conversation with Marlena de Blasi

Random House Reader’s Circle: For readers unfamiliar with your previous books, how did you come to be an expert on Italy and speak so fluently? What was the biggest challenge you encountered in mastering the language?

Marlena de Blasi: I’d been studying the regional gastronomic cuisine and the wines of Italy for nearly eighteen years before meeting Fernando. I’d travelled extensively throughout the peninsula on assignment as a food and wine writer for major American newspapers and magazines. And so by the time I met Fernando I could eat and drink rather well in Italian but could speak no more than the language of the table. Nothing else at all. I never had the least will to speak Italian. (My work took me equally often to France and it was the French language that appealed to me and which I studied.) Early on after I’d come to live with Fernando on the fringes of the Adriatic sea–after two or three days I’d say–it was evident that he would not be a patient teacher of language. His concession was to speak louder and slower and I knew that would do not much good at all. I decided it was to the markets where I would go each morning, to jump right into daily Venetian life, and to listen most of all. Everyone learns a language differently and I knew that for me, to hear it was what I needed. It was not only in the markets that I learned but on the boats, in the alleyways, on the bridges, in the shops, on the streets. I simply joined the crowds as though I belonged and soon, or perhaps not so very soon, I did.

Breakfast wine in the market bars with the fishermen, the farmers, the artisanal food makers, that’s where one learns the most. About language. About many things. Often during the early hours of the day I was the only woman among all those men tilting down their tiny glasses–one after another after another–of cloudy white torbolino. After a while I became one of the boys. And so there was never this great challenge in learning the language, never a formal, studious attempt to be perfect. I think that’s one of the reasons why I have no American accent when I speak in Italian.

What I never did nor could even consider doing was comfort myself with other Americans. To set myself up in a colony of sorts or in a ghetto of expats. A deadly game. All one accomplishes is isolation from the locals and the constant putting off of speaking the new language. Most horrid of all, one creates the opportunity to lament about the perceived pitfalls of living in a foreign country. Far better to stay at home.

RHRC: Can you tell us the origin of your nickname, Chou-Chou?

MdB: Just two weeks before our wedding in Venice, I had to fulfill an assignment for an American magazine to write about a winery in Bandol, in the south of France. Fernando accompanied me. After my work was completed, we decided to wander about for a few days. One very warm October afternoon while walking in Arles, I stopped in a little shop to buy something to tie up my very long hair. The saleswoman pulled out a great velvet box full of barrettes and such and dug about until she came up with a beautiful white taffetacovered elastic, all ruffled and ruched and bearing the Chanel initials in jet stones. She said, “Voila, la chou-chou.” Essentially, chou-chou means ‘little cabbage’ and since the hair ornament–to the French sensibility–looks like a cabbage leaf, that’s what they call it. Fernando liked the sound of it, thought the name suited, and has called me that ever since.

RHRC: What do you think accounted for the difference in how you and your husband, Fernando, perceived Villa Donnafugata upon your arrival? Were you more enchanted than he was? How did his opinion of Donnafugata change as your time there continued?

MdB: I’m always more enchanted with things than Fernando is. More open to being enchanted, I guess. Surely I sensed immediately that the villa was a place like no other I’d ever been in or seen or even imagined. At first blush, Fernando simply found the mystery of it all off-putting. I would say that our responses were in keeping with our fundamental characters.

RHRC: Early in That Summer in Sicily you note that you felt “twice expatriated . . . first from America, [then] from Venice.” Can you explain that a bit more?

MdB: Sicily is not really Italy. My second expatriation–or my sense of isolation at the beginning of my stay at the villa–was a recognition that “here is like no other place.” In other words, my newly earned comfort with living in Italy did not serve me in Sicily. I was once again a stranger, a beginner. The truth is I like that sensation.

RHRC: For your readers unfamiliar with the novels The Red Tent and The Leopard, and the movie Cinema Paradiso, can you explain what it is about Villa Donnafugata that evoked the comparisons?

MdB: How lovely it would be if we were all sitting about under the magnolia tree and had hours to talk about this. However, distilled, The Red Tent illuminates the beauty and the pain of ancient female tribal culture, which in so many instances resonated at the villa through the widows. In modern society, we women too often forget how much alike we are, how much we might help one another. Rather we become entrenched in what have come to be known as feminine intrigues: envy, competition, jealousy (all fear-based responses). Surely women have always behaved as such but maybe we do so now for even less valid motives. I don’t know. What I found so beautiful at the villa was the purity of the affection these women demonstrated to one another.

The Leopard –celebrated especially this year on the fiftieth anniversary of its publication–is Lampedusa’s brilliant historical novel which quintessentially demonstrates the Sicilian character–perhaps most particularly the decadence of the aristocracy, the cunning of the peasantry.

When Cosimo says (I shall paraphrase) “There’s always a priest, always a prince, always a girl,” surely Lampedusa came to mind. But more did this idea of continuance, which he portrays in the book. The proof that history repeats and repeats and that character is inexorable. We are all endlessly ourselves.

As for Cinema Paradiso, it was the widows’ collective enthusiasm, how they found joy in everything from washing their hair to shelling beans, how pleased they were with their lives, that recalled the little village of the film. How sad when a society loses or even misplaces the capacity for joy in simplicity. Of course, that’s when the trouble begins. When we want more than our portion.

RHRC: You’ve done such a thorough job describing the sights, smells, and tastes of Villa Donnafugata and its surrounding areas. How were you able to so vividly retell your amazing experiences? What was the process like? Can you describe your methods of recall?

MdB: I think that recall–the inclusion of sounds and smells and words, even of light–is a writer’s gift. Perhaps it’s the gift that separates, let’s say, a journalist from a writer. Notes and photos become superfluous. Everything gets saved in some far more spiritual place. A safer place I think. Travelers think to possess a scene, a face, a view, with a photo. Not trusting their own heart and soul, they ‘capture’ things at the expense of truly seeing or feeling them. But surely the creative force enters into recall. What a writer doesn’t remember, he invents. It’s the weaving together of fact and invention which makes for the best storytelling.

When it comes to food and wine, though, my recall over all these long years of traveling on my stomach has grown to be impeccable. I think I’ve earned the right to say that.

RHRC: As you wrote, were there characters whose stories you were surprised factored so heavily in the narrative? Were there additional characters whom you met during those weeks about whom you did not write?

MdB: Truth be told, not even half the story of those weeks is in the book. Certainly not half the characters. I could have written an even more complex sort of narrative and followed the events of what I might call the peripheral stories. I chose, rather, to keep the light on Tosca and Leo. I’m tempted to say much more at this point but I’ll leave it at that. Until we’re all under the magnolia tree together.

RHRC: Tosca says, “In light of the grande bouffe . . . a common, catching sulk prevailed. A whole day’s worth of grievances accumulated . . . passed about like soured milk.” Have you experienced meals like this, where the opulence of the feast paled in comparison to the guests’ disagreeable moods?

MdB: I have rarely had a guest at my table who exhibited a disagreeable mood. My friends are much too intense about their supper to spoil it with even minimal rancor. And since who’s on the chairs is always more important to me than what’s on the table, I choose my guests with care. Dining together is an intimate event. How one holds one’s knife and fork tells volumes.

In circumstances where I’ve been a guest and my tablemates are disagreeable, my defense is to speak little if at all to them, to construct a bit of a wall about myself and proceed to concentrate on my plate and my glass. I remember a Sunday afternoon last summer at a friend’s nearby country house where I employed this device. I’d found the man who was seated across from me to be a hideous bore. I smiled left and right but never once looked at him. Try as he did to engage me–after all, he was so used to commanding attention–I would not acknowledge him. Later my friend pronounced me uncivil, bad mannered. I can’t recall what else. I told her that all those handles were likely correct but that what mattered most to me was to not be false.

The opposite has happened more often, though–that is, the combination of terrible food and good company. That’s quite easy to suffer. Push the stuff around your plate, drink a lot, and, as soon as it’s decent, steal away and go to dinner somewhere else. Ah, how often have we done that.

RHRC: Can you tell us how you felt as Tosca relayed to you her experiences with the Mafia? How did this compare to (or fit into) your understanding of Sicilian history and daily life?

MdB: In the narrative I explain the truth of the great Sicilian triumvirate: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost in Sicily is church, state, and Mafia. Even one with a minimum exposure to Sicily understands that the Mafia is an intrinsic part of the very culture of the place; as one explores Sicily, the Mafia does not “come and go” in one’s experience but rather becomes a critical factor–like the weather or the language or the lay of the land. The Mafia is implicit in, organic to– sometimes more overtly, sometimes more covertly–every facet of life; surely one who travels to the island and stays within the confines of the hotel/restaurant/tour-guide experience will not necessarily sense this. On the other hand, he may so dearly want to experience some sort of Mafia sighting that he will misread or mistake even the most innocuous gestures.

RHRC: Can you tell us about your receiving Tosca’s letter in 2000? Where were you, and how did you feel as you read it? Did you suspect what she revealed to be true while you were at Villa Donnafugata?

MdB: We were living in our interim house in Orvieto, waiting for our ballroom to be reconstructed. I think I would rather not talk about those moments and the sensations therein as I read the letter. Did I suspect what she revealed? Perhaps I did. Perhaps I even knew. Did you as you read the book?

What I will say is that not even what was revealed composes the whole story. Of that I’m certain. When people ask me why do I think Tosca recounted all she did to me while I was with her, I never say. I know, but I never say–mystery being far more delicious than revelation.