Author Q&A

A Conversation with Alison Weir

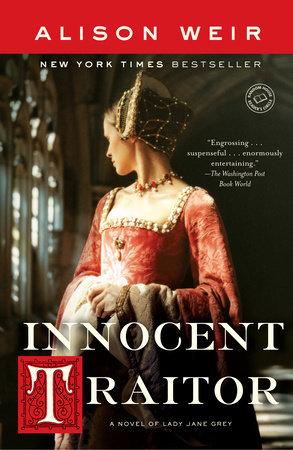

Reader’s Circle: After ten enormously popular and critically acclaimed nonfiction books, what inspired you to make the jump to fiction with Innocent Traitor?

Alison Weir: I’ve been writing historical novels for fun since the 1960s, and this one was no exception. I first wrote it eight years ago, while I was researching Eleanor of Aquitaine. It was then called Light After the Darkness, and was more “faction” than fiction. Historical novels weren’t selling very well at that time, so I just put the manuscript away when I finished it. I rewrote the whole thing a couple of years ago and was delighted when it was accepted for publication.

RC: Did your experience as a nonfiction writer and historian make it easier to write fiction, or did you have to unlearn or set aside certain habits of mind and composition in order to write the novel?

AW: It was easier to write fiction from the point of view of having seriously researched the subject and knowing the story well. But I was aware of the need to make this book sound very different from my nonfiction works, and to this end I chose to write in the first person and the present tense, because no history book could ever be written in that way. As a historian, it was vital for me to make the novel as factually accurate as possible, and I used everything that could be inferred from historical sources to make my characters come alive. Yet it was some while before I felt comfortable about coming down off the fence and letting my imagination rip!

RC: It must have felt liberating to be able to do away with footnotes for once. But fiction, especially historical fiction, has its own constraints, and I wonder if you found yourself bumping up against them.

AW: The whole experience was liberating, not just being able to do away with footnotes. I loved the freedom of being so creative. Yet it’s true that writing historical fiction does have its constraints. I was very aware that it is important to get the language spoken by the characters right, and spent a lot of time modifying original quotations–which I used wherever possible–so that they did not sound incongruous in a twenty-firstcentury text. I also found that it is generally better to show the reader– through actions and conversations–what is happening, rather than relying on narrative skills to tell the story. One problem I encountered was that, in every respect, the historical Jane comes across at every stage of her life as much older than her years, and I feared that portraying her in this way–which was essential if the book was to make sense–would stretch my readers’ credulity to the limit. So I had others talk about her precocity and her formidable intelligence, and endeavored to show that in Tudor England, children were treated as miniature adults and expected to behave accordingly.

RC: In your author’s note, you write: “Some parts of the book may seem far-fetched: they are the parts most likely to be based on fact.” This bears out the old adage of truth being stranger than fiction. Were there facts that you felt you had to leave out because they would have seemed too farfetched?

AW: I’d never leave out substantiated facts just because they sound farfetched. My editor suggested I omit a certain passage because it sounded “too contrived,” whereupon I pointed out that many historians also used to think it too contrived, but that the story came from a reliable source and is now accepted as fact by most scholars. The passage in question was the one in which the warrant for Katherine Parr’s arrest was fortuitously dropped in a corridor and found by one of her servants, who hastened to warn her.

RC: What makes the Tudor period of English history so perennially fascinating to you and to so many readers?

AW: For me, and I suspect for many other people, the Tudor period is perennially fascinating because of its dramatic events and outstanding personalities, and also because it’s the first period in English history for which we have primary sources that reveal intimate and insightful details of the public and private lives of prominent figures. There is so much human interest to captivate the imagination, a wealth of triumphs and tragedies, myths and mysteries, all played out against the magnificent backdrop of the greatest court ever seen in England, the grimmer setting of the Tower of London, the cozy splendor of country houses, or the teeming bustle of Tudor London. You couldn’t make it up!

RC: Why did you choose the story of Lady Jane Grey as your subject?

AW: Because I knew it well, I was aware that it had all the elements of a compelling and poignant tale, and I needed a story that was not too long. Above all, I’ve always found Jane an intriguing character, for she was not always a sympathetic heroine, but a feisty and dogmatic teenager who could be uncomfortably candid, outspoken, and uncompromising. I wanted the challenge of writing about her in such a way as to excite my readers’ compassion, rather than having them pity her only on account of her youth and her being used as the tool of ambitious men.

RC: In your novel, one of the most shocking things to a modern reader will surely be the extent to which women are little more than another type of property owned by often-brutal men. How, in this environment, could a woman be permitted to ascend to the English throne? Is that a quirk of history, or were there political reasons behind it?

AW: There were political reasons behind the Duke of Northumberland deciding to place a woman on the throne, regardless of the perceived deficiencies of her sex. First and foremost, he wanted to remain in power, and he could do that only if, after the death of Edward VI, England was ruled by someone malleable who would bow to his tutelage. Jane was the only member of the royal House who was suitable for his purpose, so he married her to his son, and thus bound her to obedience to her husband, who would be Northumberland’s tool. But Jane, of course, proved not to be the meek little thing the Duke had envisaged. . . .

RC: Yet despite the patriarchal culture, strong women could and did emerge, women like Jane and her cousin, Elizabeth. What accounts for that, do you think?

AW: I believe that these queens rose above the constraints of a male-dominated age simply because they were exceptional, formidably intelligent, and talented women, and also because their royal birth ensured their entrance to the political stage.

RC: Does the history of Tudor England have any relevance to what is going on politically and culturally in England and America today?

AW: One could always contrast the religious fundamentalism of the Tudor age with that which is becoming alarmingly apparent in our own society in the wake of 9/11. In both cases, we see people who are prepared to die horribly for their beliefs, and who display a lack of tolerance toward the beliefs of others. And because of our own experience of terrorism, we can perhaps understand the Tudor mind better. In other ways, though, the past is indeed another country.

RC: I was intrigued by your characterization of Henry VIII. He comes across as a much more likable figure than I would have imagined.

AW: I was trying to portray Henry VIII as Jane would have seen him on this occasion, and for this I relied on the many descriptions we have of him as a sociable, affable, and witty man who was concerned to put others at their ease. He was not always the monster of popular caricature, nor the buffoon played by Charles Laughton!

RC: Will you be writing more novels?

AW: Yes, I’m pleased to say that I have just completed my second novel, about which I’m extremely excited. It is about the early life of Queen Elizabeth I–a perilous, fascinating period when her path to the throne and her very survival were fraught with danger. Margaret Irwin aside, surprisingly little attention has been paid by writers of fiction to the years before Elizabeth became queen at the age of twenty-five, and I’ve found that it’s an especially rich subject for a novel.