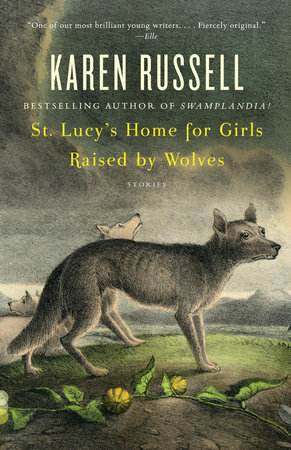

Author Q&A

A Conversation withKaren Russell author of St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by WolvesQ: Let’s address the elephant in the room: you’re twenty-four and Ben Marcus hails you as a “literary mystic” and calls your book a “miracle.” You were in New York magazine’s 25 Under 25 To Watch. What does that feel like? A: GREAT! I mean, I should probably have a more mature and measured response to that question. But really I am just bursting with joy and gratitude, of the slack-jawed, awestruck variety. This book is a miracle to me—it’s a miracle that it has an ISBN number and a cover, that it exists as a book at all when for so long it was just an ungainly word file on my computer. At this time last year, I would have been happy to place a story with the Journal of Spotted Dogs. To have found a home for the collection, it’s the great miracle of my life to date. My dream really did come true, which I think is a rare and wonderful thing to get to say. The focus on my age is a little funny to me; I mean, in some ways it seems like I should have accomplished a lot more by now. When I was at the New York magazine photo shoot, I was sitting next to fourteen year olds who had starred in Broadway musicals and invented and patented molecules. I was really flattered to be included with such an impressive group, but I also felt like a bit of a fool. Did I play three instruments with the philharmonic? Had I invented an incubator that ran on corn syrup and marbles? No, I had to inform people, no, I just imagined stuff. Pretty humbling! Q: The ten stories in ST. LUCY’S HOME FOR GIRLS RAISED BY WOLVES are mostly narrated by children. Was this a conscious choice? A: It just sort of happened that way; I never sat down to write a collection narrated by children and adolescents. But more often than not, those were the voices I ended up taking dictation from. Sometimes I’d consciously resist the child/adolescent perspective—in an earlier draft, I tried to write “Children Remember Westward” from the point of view of an older Minotaur named Jax, and thank God that didn’t work out! Maybe because adolescence is still green terrain for me, that’s the place that I kept wanting to return to. A lot of my protagonists are stuck between worlds, I think, coming alive to certain adult truths but lacking the perspective to make sense of them. There’s something about that blend of adult knowingness and innocence that I find incredibly compelling. For better or for worse, that’s the voice that I feel most drawn to at this moment. In future collections, I’d love to try and channel different sorts of voices, older, fainter, stranger voices.Q: In “The Star-Gazer’s Log of Summer-Time Crime,” the protagonist muses, “I guess that’s what growing up means, at least according to the publishing industry: phosphorescence fades to black-and-white, and facts cease to be fun.” The title story, “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves” is about a pack of 15 girls, raised by wolves, who are taken away from their parents and reeducated by nuns to enter civilized society. What are you saying about the nature of growing up? A: Uh-oh! These sorts of questions always make me nervous, because to be honest I feel I’m lying a little bit, making up a story about my stories. For starters, I don’t want to sound like a dufus—anything that I’m trying to say about the nature of growing up, I’m sure other writers before me have said with greater insight and eloquence. Also, if I could just say the thing outright, I probably wouldn’t need to strand my young protagonists inside giant shells or exile them from their wolf-parents. They could just play whiffle ball and eat ham sandwiches for awhile, and then one day they’d wake up adults. There’s this line that I love from a Mark Jarman poem: “and like the joy of being, and becoming.” And I wanted some of that joy to come through in these stories. But I also think the underbelly of that feeling is this dark and ferocious sense of loss. In the title story, for example: who exactly are those wolf-girls en route to becoming?Q: The parents in your collection are often absent or tragically flawed: a proud Minotaur for a father, a mother who is always “draped over some jowly older individual,” a set of wolves for parents. Seems pretty tough to be a kid these days, at least for your characters. A: I think it’s pretty tough to be a parent, too. I wouldn’t judge the parents in this collection too harshly; that Minotaur, for example, has to struggle against prejudice and the prison of his own anatomy as well as, you know, snakes. And also dysentery, and the impossible price of corn. Or the wolf-parents, who wanted a better life for their children. That sort of fierce parental love can warp into strange shapes when confronted with the outside world and its dangers, I think.And it is hard to be a kid these days! I don’t know if it’s like this for everybody, but I felt like I was born with a deep and queasy suspicion that something is awry. I think the hard part is that most kids have this sense that they have to set this “something” right, despite a poor match between the world’s problems and their puny kid-resources.On a side note, I should mention, just because I’m paranoid about readers mistaking this, that these parents are not my parents. My parents are the most wonderful people you will ever meet. My mother would only drape herself over a jowly older individual if he required the Heimlich. My father is a deeply wise and kind and humble man, and mercifully he’s 100 percent human, no kind of Minotaur. Q: How did you come to pick the title story? Is “St. Lucy’s” your favorite or did you just decide it was a good title?A: “St. Lucy’s” is my favorite story, most of the time, but all of these stories have been my favorite at one point or another. Most recently it was “Accident Brief,” which was a “troubled” story that didn’t look like it was going to make it into the collection for awhile. It’s like asking, who do you love more, the straight-A, varsity athlete or your wall-eyed mulligan child? My favorite story is often the one that nobody wants to take to the prom. Then I just want to tamp down its cowlick and put it in orthopedic sneakers and set it to dancing. As for the title, it was originally going to be “Ava Wrestles the Alligator.” Then my brother strenuously vetoed this, on the grounds that it sounded like a “Hooked on Phonics” story. I seriously considered all sorts of bad titles (see below), some of which I can’t even admit to here. At first, I thought “St. Lucy’s” was too long to be the title, but it really grew on me. My agent suggested that I find a new saint’s name (originally, St. Lucy was St. Augusta, making the title even longer!). So I dug up my old “Catholic Picture Book of the Saints” and did a lot of lame internal agonizing about the relative merits of St. Ulrich (the patron saint of wolves, but too much like Skeet Ulrich?) and St. Gertrude (too much of a hiccupy g sound in the title?). Finally I settled on Lucy, always a favorite name of mine. Lucy is the patron saint of blindness, which seemed to work thematically given the “blindness to vision” reformatory promises made by the school. Also she’s the patron saint of authors, and I’ll take whatever help I can get.Other titles we considered include:-Cheering for our Species (My agent suggested this one, from a phrase in the “Ava” story. I liked this one a lot, actually, but I was also worried about the cover art that such a title would inspire. I pictured a bear in a pleated cheerleading skirt, doing a half split, the book’s title coming out of her megaphone in bubble letters. Like a Bernstein bear, but sluttier.)-Swimming Past Extinction (Dave King wisely informed me that gerunds in titles are so passe!)-Children Remember the Westward Migration (My Dad said this sounded too much like a History Channel snooze-fest.) Q: Many of the stories in ST. LUCY’S are set in the surreal marshes of the Florida Everglades, which is an area you’re familiar with. Why do you prefer this setting? Do you think you’d be writing about the same places if you grew up on a farm in Iowa? A: Florida, if you haven’t been, is a place that you should go. Southern Florida is a separate universe from the rest of the country. The ocean and the swamp offer all sorts of metaphoric seductions, I guess, but they are also literally, unfathomably mysterious. The Everglades in particular must be one of the strangest places in the world. Weird stuff washes ashore. Tiny, prehistoric lizards live in your mailbox. I don’t think you realize until you leave South Florida how bizarre and wonderful it is. For example, the manatee. My family and I would feed lettuce to this cow that lived under the water, a hundred feet from the house. It wasn’t until I went to college in the Midwest that I realized how strange and special this transaction was. It’s also a community of Cuban exiles, and I’m sure that Miami’s second-generation sadness got into my bloodstream somehow. It’s in the water supply down there, this hereditary nostalgia. All those festivals in Little Havana, old women shouting themselves hoarse with a sort of boisterous homesickness.As for Iowa, I think that setting gives rise to theme and meaning in a lot of these stories, but it works the other way, too. I’m sure I’d have found a way to graft my preoccupations onto Iowan farms. There’d be ghosts in cornfield and old aeroplane hangars. Wallow and Timothy would find a supernatural horseshoe or something. The Bigtrees would wrestle milk cows. Q: Who are your literary influences? A: Flannery O’Connor, Kelly Link, Steven King, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mark Richard, Wallace Stevens, Carson McCuller, Mary Gaitskill, Alexander Hemon, Italo Calvino, Nabokov, Katherine Dunn, Ray Bradbury….yeesh, I could go on. I had this private/public reading split when I was a kid, Austen and Dumas and those Brontes for the adults, “Fear Street” and Frank Herbert in private. Q: What in your own life made you want to become a writer? A: Reading, definitely. I loved reading so much; I mean, I still do, but not with that sort of illicit midnight intensity. I was such an anxious kid, and reading was a way out. At sleepovers, I would sneak away and lock myself in the bathroom and read the other kids’ books. Here was a way to step-out of your child’s body and into the mind of a Salem witch or a bunch of warring rabbits. It’s still amazing to me. It was spooky and intimate and totally intoxicating, to step into an author’s private rooms. I’d read the words and they became my rooms. Then I wanted to be a writer myself, to do to others what these authors were doing for me.At the risk of sounding like a lameball, it’s true magic. You can put three letters on a page, “owl,” and send an owl swooping through another person’s brain. Maybe “owl” is not the most compelling example here—picture a stranger bird, or a bunch of birds. It’s a weird semantic migration, writing and reading. Picture a flock of birds alighting from the writer’s brain and converging inside the reader, this strange shuddering weight settling on the branches of the reader’s mind. Now I’m probably over-romanticizing a good bit—it doesn’t always feel that way, not if you’re reading the classifieds or writing in your sweats. But there is something bizarre and wonderful to me about the whole enterprise. I’m also still at a stage where it feels a little embarrassing and fraudulent to self-identify as a writer. Smarmy, even. I’m still trying to get used to that.Joan Didion has this quote about how writers tend to be anxious “keepers of notebooks” afflicted with a “presentiment of loss,” and I think that’s as good a hypothesis as any. I found one of my first-grade notebooks recently, and I see that I had some early templates for plot. My first story, in its totality, was: “Once upon the time there was a forest of peaceful unicorns. Then there was a flood!”Q: I hear that this is your second encounter with book publishing. What was your first?A: I worked for Persea Books, this truly fantastic independent press that in retrospect should probably never have hired me. When I said I was “proficient in Excel,” what I meant was that I’d seen Excel spreadsheets on other, smarter people’s computers. I’m pretty sure I only got the job because of my huge ugly coat, this trash-man coat that could double as a life-saving tent in a blizzard. My boss needed somebody who could walk through blinding snow to the post office, and after pinching the fabric of my coat, he determined that somebody was me. I could have sent that coat in on a hanger to my interview, and it would have gotten me the job. At Persea, I worked “publicity;” in practice, I sent emails and I sorted regular mail and on Thursday I took the trash out. I liked taking the trash out because it was so frequently filled with my mistakes—reams of misprints and upside-down letterhead. I can’t tell you how many Jiffy bags erupted because of my shoddy tape-jobs. Did you know there is a wrong way to staple? It’s true. I have thumb scars to prove it. I loved that job and the folks at Persea, but it probably wasn’t the best match with my skill set. Q: In an interview with the New Yorker after “Haunting Olivia” was published in its annual Debut Fiction issue, you said that writing short stories is like a string of first dates. What did you mean by that? A: Stories are great for the commitment-shy. Whenever I begin a new story, I have to fight down a rabid, bride-to-be hopefulness—is this story “the One?” Will our casual fling blossom into a 600-page novel? Then, the initial thrill wears off, and it’s a struggle to keep the conversation moving forward. Somewhere around the late-middle of most stories, I get a panicky, “check, please!” feeling. And then it’s over, and I get to exit the story with a misty gratitude for our time together, and a deep relief that we never have to see each other again.Of course, I haven’t gone on enough first dates or written nearly enough stories to legitimately make this analogy. I’m basing this on a small group of stories and one stupendously awkward night at an Ethiopian restaurant. Q: You’re a recent graduate of the Columbia M.F.A. program. Are you still involved in with a community of writers in New York and is that important to you? A: Well, technically I don’t graduate until August, but many of my friends from the program have already graduated and moved away. Which has been a tough adjustment this year, after two blissful years of reading and writing and hanging out. I met the most amazing people in my Columbia workshops, and I hope that we will continue to be each others’ friends and readers for life. I’m not actively involved with any workshop group right now, but I definitely do still feel hooked into a supportive community. And I live with my best friend, Carey McHugh, the best poet this side of Jupiter–watch for her to win the National Book Award. We “support each other’s writing,” by which I mean we curse like sailors about not writing enough and watch a lot of "America’s Next Top Model."Q: What are you working on right now? A: I’m working on a coupla new stories and a novel, Swamplandia!, about the Bigtree Family Wrestling Dynasty. (Ignore what I just said about “America’s Next Top Model.”) It’s set in the Florida swamp, and it picks up where “Ava Wrestles the Alligator” leaves off.