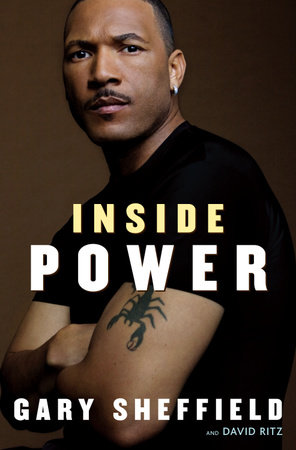

Author Q&A

Lynda Barry is a writer and cartoonist. She’s the author of several books,

including Cruddy and One Hundred Demons.

Lynda Barry: Where were you and what were you doing

when this story first showed itself to you?

Anne LeClaire: I was in the middle of a writing residency

at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, which is situated

in a rural town in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

One day I went into town to get a haircut and saw a poster in

the local beauty shop advertising a Glamour Day, just like the

one Tallie describes. "They make you look like a star," the

owner told me as she trimmed my hair, summing up in this

single sentence the magic formula. This started me thinking

about the way Hollywood acts as a polestar in our culture,

pulling us along in its wake, however much we deny its magnetism.

I saw in my mind the young girl who would be

Tallie, a teenager wanting to be transformed. It was just a

glimmer, but enough to get me started, although at the

time I thought it would end up as a short story. Out of this

beginning–the daughter of a starstruck mother, deserted

for a dream–a story was formed. I have to add that in the

interest of research I did sign up for Glamour Day, but truly I

did not end up looking like a movie star. More like a female

impersonator.

LB: Was that first glimmer like a picture? Did you see

Tallie in your mind’s eye?

AL: It was actually more a feeling than a visual impression.

When I looked at that poster, I felt the yearning a young girl

might feel, an ache really, the wanting to be something

more, more than a person’s particular geography or circumstances

suggested was possible. That sense of longing was

central to the story as the work progressed: Tallie’s longing

for her mama, for a relationship with Spy, for a connection

to her father, for information about how to become a

woman, and, of course, her desire to be beautiful. Out of that

initial sense of hunger, a visual did surface, and it was of Tallie

standing in that beauty parlor.

LB: I love the Klip-N-Kurl! It seemed a perfect place for

a teenage girl who had lost her mother (twice!) at such

a critical time in her adolescence. It reminded me of a

fairy tale in that way. Many fairy tales begin with an

adolescent girl who has lost a good mother who has

been replaced by an evil stepmother. I’ve often wondered

if it isn’t a way to tell the story of what happens

to us when we hit adolescence and begin to separate

from our mothers. That wonderful, beautiful, loved

mother from our childhood seems suddenly transformed

into an unreasonable, out-of-it, controlling old bag.

Tallie didn’t have a chance to have that crucial relationship

with her mother.

AL: Exactly, Lynda. Even for the brief period when her

mother returned from Hollywood, Tallie couldn’t explore

normal adolescent separation and independence. The few

times she allowed herself anger, it felt too dangerous because

her mother was ill. There wasn’t even an evil stepmother to

rebel against. So to continue the fairy-tale theme, Tallie had

to create her own bread crumb path to negotiate her way

to womanhood because she didn’t have the road map a

mother might provide. I don’t know if I’ve ever told you, but

I watched my three nieces grow up without a mother–they

were eight, eleven, and fifteen when my sister died–and

witnessing the confusion, pain, and significance of their experience

helped me slip into Tallie’s skin.

LB: That’s one of the things that fascinated me about the

book. There is no evil stepmother whom Tallie can hate.

That’s a tough position to be in, having your Natalie

Wood-look-alike mother be forever preserved as good,

perfect, young, and most of all, more beautiful than

you’ll ever be. It’s also a tough position for a writer to be

in, because a horrible person makes a writer’s job a

whole lot easier and the story follows a certain path. But

no horrible person shows up directly in Tallie’s life. I

kept waiting for one and when I realized no horrible

person was coming, I felt this odd sadness, a loneliness

of being stuck in her position exactly. It was as if Glinda

the Good Witch in The Wizard of Oz got the ruby slippers

and then died with them on. She’s the Good Witch, so

how can you get mad about it? Our earliest love for our

mothers is like that, like Glinda the Good Witch, like the

original Eden. It was so lonely following Tallie through

all her temptations and transgressions, knowing there

wasn’t anyone who cared enough to throw her out of

Eden. In the end she had to throw herself out.

AL: It is lonely when no one cares enough to toss you out of

Eden for your sins, or even notice them. But is it worse if

someone tries to keep you stuck there? And you are absolutely

right about it being easier for a writer if there is a

wretched character threatening the heroine.

LB: Beauty is a main character in this book. And as soon

as I read Natalie Wood’s name, I knew exactly what kind

of beauty you meant. There is no way to be more beautiful

than Natalie Wood. I know what it’s like to be the

plain-faced child of a beautiful woman. People always

said my mother looked just like Ava Gardner and even

now I can’t look at a picture of Ava Gardner without

getting a sad, empty feeling. It broke my heart to think

of Tallie watching Natalie Wood movies.

Was your mother beautiful? Your sister?

AL: My older sister was stunning, and people were always

telling me how beautiful she was. I was the duckling to her

swan. And I know exactly what you mean about that hollow

feeling you experienced watching Ava Gardner. And about

the desire to be beautiful. A lot of what I was exploring during

the writing was this territory of desire. Not just the longing

for beauty, but desire of all kinds. Where do our dreams

and aspirations come from? How do our own experiences

shape our desires? How do dream merchants like Hollywood

and Glamour Companies form them? How do our dreams

shape our lives?

LB: And what happens when you get your wish? Tallie

prays so hard for her mother to return and when she

does, it turns out she’s dying. Did your sister come up

for you a lot while you were working on this?

AL: Here’s the odd thing. All the time I was writing it, I

wasn’t consciously thinking about my sister or my nieces,

but when I read over the completed manuscript, I had that

lightbulb experience of "My God, I’m writing out of my own

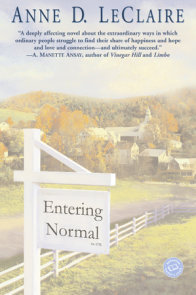

history." I had a similar experience with Entering Normal. Like

I’m the last to know. Does this happen to you, or are you

very aware of where your material is coming from during

the process?

LB: When I’m writing and it’s going well, it’s more like

slow dreaming. Half of my struggle is to be able to stop

thinking and just go along for the ride. I often tell myself,

"Just be the stenographer. Your only job is to be

the stenographer."

Someone once pointed out how odd it is that we

can remember our dreams, we’re aware of dream selves,

but our dream selves seem to have no awareness of our

waking life. What we call our "real" lives. You never say,

"Man, I had the weirdest reality yesterday."

I think that may be part of why it’s so often the case

that writers are the last to know how close the story

may be to their own experience. A story has no awareness

of its author. Which feels very odd after living with

a character for as long as it takes to write a book. They

feel so real to us, but to them we don’t exist, can’t exist.

And there’s a great relief in that, somehow. To give

yourself over and, for a little while, stop existing. I

wonder if it isn’t somehow a bit like flying a plane–

which you also do. Are writing and flying planes

similar?

AL: I love your statement that a story has no awareness of its

author. It feels odd–and a little sad–to think of characters

that are so very real to me not even knowing I exist. I guess

we humans want reciprocity.

About flying and writing: I’ve never thought about it before,

but there is a connection in that both of them lift me

out of my daily reality and present me with a different perspective

of life, another way of looking at things. Both also

require a great concentration, the kind of intense focus that

is almost like meditation.

LB: When the writing is going well, it’s a different state

of mind. It doesn’t seem to include a lot of thinking or

planning. It is absolutely the best when it doesn’t even

feel like writing. When it’s like the deep state of play

you see kids go into sometimes. From an adult’s point

of view, the kid is playing with toys. But from the kid’s

point of view, the toys are playing with him. He doesn’t

have to plan out a story for the toys. As long as he’s not

self-conscious, the stories will happen by themselves.

I’ve always thought that self-consciousness was an

odd name for that feeling because it’s really consciousness

of others. My very WORST writing experiences

happen when I’m aware of "the reader," a reader who

doesn’t even exist because until the story exists there

can be no reader, and as long as I’m concentrating on

the reader there can be no story. My worst days are

when I’m frozen into a state of worry about what the

nonexistent reader thinks about my nonexistent story.

AL: But the trick is losing self-awareness, shutting out the

critical mind. Then bliss. For me, writing flows when I don’t

plan it out in advance. The only novel I never got published

was one I mapped out in detail first. By the time I sat down

and wrote it, it was lifeless.

But to leap in, not knowing exactly where the story is

going, takes trust, doesn’t it? Some days I think writing is one

huge act of faith. You set out with that glimmer and not

much else, and trust if you write straight and true and with

as much courage as you can muster, a story will result. That

is what is required of us.

And I think the worst writing advice I’ve heard is that

writers should have a particular reader in mind for whom

they are writing. My experience has been that putting the

focus on the reader (or editor or critic) lifts us out of the

story and can lead to some god-awful pretentious prose.

LB: Plus, it’s no fun.

We became friends in the early 1990s at an artist

colony where we were both working on novels. The

first thing I noticed about you was how much you genuinely

loved to write. You had an exhilaration about it

that I loved, and your way of talking about writing was

so unpretentious compared to many writers I’d met. I

was just starting work on a novel that became Cruddy

and felt really shaky on my feet about it. You were so

supportive and practical and helped me so much. I

know you have many readers who would love to write

a book but have no idea where to begin. What advice

would you give them?

AL: Right back at ya’, Lynda. Your humor and exuberance

and honesty attracted me right from the get-go.

Advice to writers? Hmmm. I guess the old chestnuts:

Take risks. Pay attention. Tell the truth as you see it. And

write, write, write. Write not for fame or fortune or recognition,

but because it brings you joy.