Author Q&A

A Conversation with Tracy Kidder

1. Where did the idea for Home Town come from? How did it evolve?

About five years ago I went to Haiti to do a story for The New Yorker. I saw a country where almost nothing worked. I came home, through the crowds of ragged, starving children at the airport in Port au Prince, believing that competent government and good engineering must represent a moral good, because their opposites clearly led to so much evil, so much human suffering. And I started to think in a new way about the largest town near the place where I live– an old New England town called Northampton. It was a place that seemed to work very well indeed, and I wondered why.

2. What is your relationship to Northampton, Massachusetts?

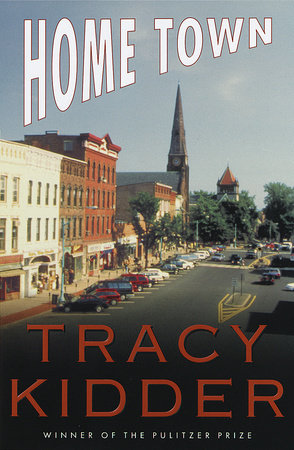

I have lived near Northampton for almost 30 years. For me, and for many people who live in what is called The Pioneer Valley (which is the watershed of the Connecticut River within Massachusetts) Northampton has long served as a center. It’s a meeting place, a shopping place, a dining-out place, a place to hear music or see a movie. It’s a pretty town, maybe prettiest from the distance I used to see it from. Up close, it turned out to be, not different, but a lot more complex than I’d imagined. A surprising place, when looked at closely.

3. Much of the book is seen through Northampton police officer Tommy O’Connor’s eye. How did you find him?

I wasn’t sure that Northampton would make an interesting setting for a book, exactly because it seemed unlike Haiti, because it seemed to make entirely too much wholesome sense. Then one day, at the local gym, I started talking to a very friendly young man with a shaved head. After we’d chatted for a while, he remarked, "You don’t remember me, do you? I stopped you for speeding five years ago."

Then I did remember. This was the shaved-head of a once curly-haired young cop who had given me a ticket and had afterward said with great sincerity, "Have a nice day." I remembered him mainly because he’d stopped my wife for speeding later that same day, and he hadn’t given her a ticket. As I learned later, this cop–his name was Tommy O’Connor–usually didn’t give women tickets, because he hated to see women cry. Paradoxically, if a woman did start crying, he’d reason, "Well, she’s already upset. I might as well write her up." (Something for female speeders to remember–it isn’t always best to cry. Better just to look sad and repentant.) Anyway, at some point Tommy the cop said to me in words like these, "Why don’t you come out in the patrol car with me some night? I’ll show you a Northampton you never thought existed."

4. What compelled you to write about O’Connor and what he saw every day?

He turned out to be an extraordinary cop, smart and diligent and funny, very good at his job, and deep down, almost too kind for his own good. Riding with Tommy O’Connor was fun, and it was interesting. I’d ride with him most nights and spend the days poking into the lives of other townsfolk, often ones he’d led me to. He delivered on his promise. Through him, I began to see a town I hadn’t thought was there. The picture that I’d held in my mind of the place began, not to fall apart, but to fragment, the way a pointillist painting turns into a bunch of small dots if you move too close to it–except that the dots in this case were in themselves interesting, and sometimes appalling. After awhile, I could walk down the lovely Main Street past its fine old, refurbished buildings and its colorful open-air life, and conjure up a vision of a whole bunch of things happening elsewhere, nearby but largely out of sight.

And Tommy was a lot of fun to ride around with. He was certainly forceful, but he wasn’t one of your dour, mean, thoroughly cynic cops. Sometimes when his job brought him to the Emergency Room, he’d get one of the nurses to take his blood pressure. Repeatedly, the measurements showed that it rose, not dangerously but markedly, when he was in uniform. Ten years as a local cop in his small native place, and he still felt excited when he went out patrolling in his town and heard the desk officer’s voice come over the radio, calling for him.

I remember this innocent little incident: "Eighty-three," said the desk officer’s voice. "We have a call for a dog locked inside a car."

The desk officer’s voice sounded weary. Tommy’s voice rose. "Why do people call the police because of a dog in a car?" he cried, as he headed toward the scene. "Why not? Who else they gonna call? This is a great job."

Tommy’s story seemed like a classic American story to me. A boy grows up in a town and comes of age believing that he has spent his childhood in the best of all possible places, and he fulfills a dream he’s had since infancy–to become a local cop and to work to keep the town just as orderly and safe as it had been when he was a boy. But not long after we meet him, he comes up against the truth–that if a person lives long enough in the same small place, sooner or later something he really doesn’t like is bound to happen all too close to home.

In my book we spend about a year and a half with Tommy. It’s a time in which, in effect, the landscape of the town changes for him, a time during which, in a sense, he grows up–always a sad event for the happy child. So if I were forced to summarize my book in a few words, I guess I’d say that it’s about an old American town, seen in the reflection of lives lived in it, chiefly the life of a person who knows and loves the place so well that in the end he has to leave it.