Author Q&A

Recently, David Kamp took time to tell Broadway Cooks more about his book.

Broadway Cooks: What makes this an unprecedented time for the American food world?

David Kamp: If you think about it, you go to France and you don’t just see the museums, see the Louvre; you also make a big deal of eating and the food. The same goes for Italy; you don’t just go to the Spanish Steps; you go to the restaurants, you go to the markets. And we’ve finally reached that point in America–where food is a cultural pastime; where it’s actually something we take as seriously as we take the movies, the sports teams we follow, and the books we read.

What are some examples of how the American culinary revolution has shaped our lives?

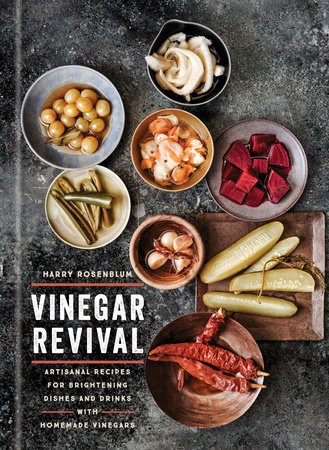

Anyone who is currently an adult can think back to their childhood and say ‘So much has changed!’ There are so many things out there that we didn’t have when we were children. Whether it’s going to a farmer’s market in your city–which your city didn’t used to have–or going to your regular supermarket in the suburbs and seeing goat cheese and arugula in the cheese and produce sections. Even croissants, which are ubiquitous–you can get them at gas-station convenience stores–were exotic until about the mid 70s in most places.

Who are some of the major figures in your book—and in this movement?

American food has a long history, and I don’t pretend to tell the whole story. My starting point is James Beard, who moved to New York in the 30s with the dubious intent of becoming an actor or theater person even though he was a big fat guy with not a whole lot of acting talent. But he was an excellent cook and a charismatic teacher, traits he inherited from his mother, who ran a hotel in Oregon. And the story really begins with him giving up his theater career, reluctantly taking on food and cookery and teaching cooking as a career–and this being a very reluctant decision, because it didn’t seem like an honorable profession to him. And yet he did as much as anyone to turn that tide and change cookery and food and eating into cultural pastimes, not just something you did out of obligation, or out of the biological imperative of fueling yourself.

Apart from Beard, the other two who make up what I call the Big Three are Craig Claiborne and Julia Child. Pretty much everyone knows who Julia Child is. She co-wrote the epic cookbook Mastering the Art of French Cooking, which came out in 1961, and then a little after that had her TV show on public television, The French Chef. And she was really the one who demystified the idea of ambitious cooking. Americans were already enthusiastic home cooks, but it was more to do with cakes and pies and pastries, or simple, everyday fare like meat loaf. She was the one who said it was okay to aim high once in a while, to try to do things that French chefs do in restaurants. And she just brought such humor to what she did—she would laugh at her own mistakes, which took away the intimidation factor. She enchanted America. By 1966, she was on the cover of Time magazine.

Craig Claiborne, like James Beard and Julia Child, came to the food world relatively late in his life—already in his mid–to late 30s, having failed at pretty much everything else he tried to do, whether it was being in the Navy or going to hotel school. (He went to hotel school but realized he was never going to run a hotel.) In 1957, he became the first male food editor of The New York Times. Food writing in the newspapers had always been the province of what was called the “women’s page,” which was basically a home–ec ghetto, and kind of patronizing to housewives. It was a gutsy move for the Times to put him in this position, and a gutsy move for Claiborne to say, ‘Hey, this is where I want to be. This is where I think my journalistic instincts are most applicable.’ He invented the idea, really, in America, of food journalism: of taking food seriously, writing about it in a way that wasn’t piffley or purely for housewives, and not condescending to housewives who happened to cook seriously. He invented the starred restaurant review in America, the idea that, “Oh this restaurant got three stars in the Times, so we need to check it out.” He also created the notion of food journalism as a legitimate journalistic beat for a newspaper. He would go out and cover what was happening in people’s kitchens and restaurants. Were it not for him, there are a lot of people we might not have heard of otherwise, such as Marcella Hazan, who is now America’s great authority on Italian food and has published a lot of books; and all the French chefs who came to America after World War II, especially Pierre Franey, who became Claiborne’s friend and collaborator.

Haven’t Americans always liked to eat? What’s different about the interest in food that you’re exploring in The United States of Arugula?

I am not arguing that there was no American cookery until the last few decades, nor am I arguing that there was no good food. But the breadth and scope of it really started to change in the last few decades. As long as there’s been a United States of America, people have been able to eat well if they choose to. But in truth, American eating habits was pretty disgusting for the majority of people in the 18th and 19th centuries. And really, it was in the 20th century, with the advent of such popularizes such as Child, Beard, Claiborne, that we suddenly could eat well in a way that we couldn’t have before. It crossed class lines. In the 19th century, dining out was for rich people, Gilded Age robber barons like Diamond Jim Brady, who went to places like Rector’s or Delmonico’s and ate enormous, multi–course meals of terrapin and canvasback duck and oysters; that’s changed. Food also changed in terms of crossing ethnic lines. In the old days, if you weren’t Italian or Italian-American, it was borderline scandalous to eat garlic, let alone something more progressive like pesto or arugula; in It’s a Wonderful Life, mean Mr. Potter chides good-hearted George Bailey for giving loans to Italian immigrants and says George is “frittering his life away playing nursemaid to a lot of garlic–eaters.” We were walled off from other cuisines by out own ethnic and cultural biases. But that’s all changed because the food world got democratized and more polyglot in the mid-20th century, and has only become more so.

Are the foodies accessible as interview subjects? How are they different from the other celebrities you’ve interviewed?

My day job is as a Vanity Fair writer, which has given me an opportunity to write about a lot of famous people in the realms of film, music, and so on. One thing you discover—one of the nice things—in writing about the food world is that the crème de la crème are still very accessible, A) Because they still haven’t been written about in great depth. They’re mostly written about in newspaper food–section terms or magazine terms, where the discussion is pretty superficial. So they’re flattered to be engaged in a deeper discussion of what makes them tick. And, B) they’re in the hospitality business, so, inherently, they want to talk, they like shooting the breeze, they like other people—with a few exceptions. There are a lot of great raconteurs out there, like Jeremiah Tower, who was the first well–known chef the Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse. And Mollie Katzen, who wrote the vegetarian standby The Moosewood Cookbook and has a great sense of humor and perspective about how naïve her cooking was in the 1970s. And the other good thing is that these people often cook for you while they tell you stories — which is no small fringe benefit! André Soltner, who for years was the chef-owner of Lutèce in New York, made me the best omelet I’ve ever eaten in my life.

What do you make of the celebrity chef phenomenon and the emergence of Las Vegas as a one-stop shop for fine dining?

The celebrity chef phenomenon is a double–edged sword. Some see it as a violation of the code of honor that Andre Soltner represented. Soltner lived above his kitchen, worked at his restaurant six days a week, and closed the restaurant on his day off and when he went on vacation. He was the purist ideal. Yet a lot of younger chefs now say, “Yeah, but he never made any serious money. He might be happy with his life, but that’s not how I want to live.” Also, some chefs, like Mario Batali and Wolfgang Puck, make the point that opening more restaurants gives them an opportunity to nurture and promote all the younger staff they’ve trained. Now, what can happen is that a celebrity chef can suffer as a result of his celebrity. Emeril Lagasse is a good example of this. Anyone who’s a chef, whether it’s Batali or Puck or Chicago’s Charlie Trotter, will tell you that he’s one of the best chefs in America, period. But TV is inherently reductive and about entertainment values, so Emeril’s TV persona is kind of simplified and goosed up. If the guy cooks for you, his skills and creativity are unimpeachable, but because of that “Bam!” and “Kick it up a notch,” lots of people think he’s a cheeseball or a hack. I asked Emeril if that’s a problem and he said yes, it is. He said that Tim Zagat of guidebook fame confronted him at the James Beard Awards one year and said “You’re like a used car salesman. You’re bringing shame to our industry.” Emeril got really emotional about this, on the verge of tears. And that kind of dynamic is fascinating to me, and it’s something I get into in the book. In the later chapters, I talk about how the celebrity chef phenomenon is something the food world is still grappling with. There’s a lot in this book about who these people are, behind their public images. For too long, we’ve imagined the food world as this twee, precious little place that no one takes seriously. But it’s a world of big ideas and crazy ambition, and of real talent and real passion. Food people are as fascinating—and brilliant, and contrary, and rivalrous, and inventive, and compelling—as rock musicians, politicians, novelists, and movie directors. This book pulls up the curtain on that.