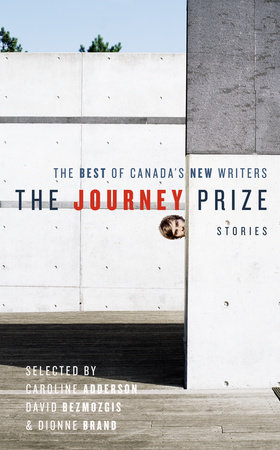

For almost two decades, The Journey Prize Stories has been taking the pulse of Canada’s literary scene, presenting the best stories published each year by some of our most exciting up-and-coming writers.

Among the stories this year: A holdup marks the beginning of a spectacularly ill-fated romance between a free spirit and a man with the heart and soul of “a criminal born.” When her young imagination is captured by a photo of a Hungarian refugee child, a girl becomes determined to make the orphan a part of her family’s life. In a story set in Venice, amid complications both legal and romantic, a Canadian expat comes to understand the restless path his father’s life has taken. A boy discovers something about fame, mortality, and triple force fields when the kids in his neighbourhood vie for a coveted spot on an arcade game’s high-scores list. In a modern fairytale with a twist, a woman who is always cold is given an unexpected gift. A near-drowning in the Indian Ocean reveals difficult truths to a documentary filmmaker during what is supposed to be a career-advancing trip.