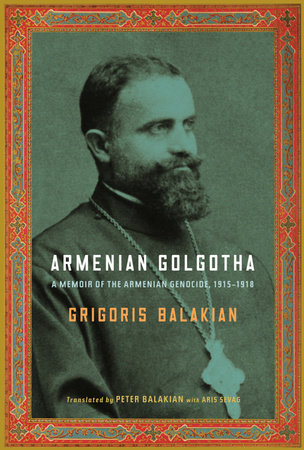

Armenian Golgotha

By Grigoris Balakian

Translated by Peter Balakian

By Grigoris Balakian

Translated by Peter Balakian

By Grigoris Balakian

By Grigoris Balakian

-

$21.00

Mar 09, 2010 | ISBN 9781400096770

-

Mar 31, 2009 | ISBN 9780307271389

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Dry Storeroom No. 1

Living Ready Pocket Manual – First Aid

Essential Techniques of Landscape Drawing

The Little Book of Atheist Spirituality

Pull

Kingpin

The Roads to Modernity

Revival 2.0: How the Obama White House Is Making Its Political Comeback

Our Robots, Ourselves

Praise

“A fascinating first-hand testimony to a monumental crime.”

—The New Yorker

“Gripping. . . . A powerful and important book. . . . It takes its place as one of the key first-hand sources for understanding the Armenian Genocide.”

—Mark Mazower, The New Republic

“Powerful. . . . Riveting. . . . A poignant, often harrowing story about the resiliency of the human spirit [and] a window on a moment in history that most Americans only dimly understand.”

—Chris Bohjalian, Washington Post

“An immensely moving, harrowing memoir that instantly takes its place as a classic alongside Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz and Elie Wiesel’s Night.”

—Carlin Romano, The Chronicle of Higher Education

“Read this heartbreaking book. Armenian Golgotha describes the suffering, agony and massacre of innumerable Armenian families almost a century ago; its memory must remain a lesson for more than one generation.”

—Elie Wiesel, author of Night

“An appalling and magnificent book. . . . It owes its existence to [Balakian’s] determination to survive to write it . . . a sacred task that gives him the strength to persevere through the impossible circumstances that killed well over a million of his countrymen.”

—Benjamin Moser, Harper’s

“Shocking and brilliant. . . . Exquisitely rendered. . . . This book has the feel of a classic about it, and I suspect that future writers on historical trauma and its representation will turn eagerly to Armenian Golgotha. It’s a massively important contribution to this field.”

—Jay Parini, The Chronicle of Higher Education

“An extraordinary narrative . . . beautifully translated. . . . Armenian Golgotha will influence Armenian genocide studies for decades.”

—John A. C. Greppin, The Times Literary Supplement (London)

“Monumental. . . . Balakian provides strong evidence that these gruesome proceedings were carried out under official orders from the highest level. . . . For generations to come Armenian Golgotha will remain a first-hand documentation of a historic tragedy written from the perspective of a talented scholar.”

—Henry Morgenthau, III, Boston Sunday Globe

“[A work] of exceptional interest and scholarship.”

—Christopher Hitchens, Slate

“The translation and publication of Armenian Golgotha in English is long overdue. It constitutes a thundering historical proof that those who deny the Armenian Genocide are engages in a massive deception.”

—Deborah E. Lipstadt, author of Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory

“Groundbreaking. . . . Comprehensive. . . . Sobering. . . . Armenian Golgotha is replete with narratives that focus on collective suffering, marking this memoir as one of the few to explicate the true nature of the crime. . . . Balakian’s memory is extraordinary, but so, too, are his intellect, his compassion and his ethical obligation to immortalize his beloved co-nationals.”

—Donna-Lee Frieze, The Jewish Daily Forward

“An Armenian equivalent to the testimonies of Holocaust survivors like Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel.”

—Adam Kirsch, Nextbook

“The descriptions of the Armenian genocide are striking and the author spares his readers none of the gruesome details. . . . A riveting and powerful indictment of a genocide that became a paradigm for future genocides.”

—Holger H. Herwig, The Gazette (Montreal)

“An essential memoir, a lively and extraordinary life story. . . . This is more than an eyewitness account, it is a masterful history in its own right.”

—Seth J. Frantzman, The Jerusalem Post

“Weighted with eyewitness accounts and distinguished by Balakian’s prodigiously sharp memory, this book is not a scholar’s history, of course, but an educated prelate’s, with an enviable grasp of Ottoman and European history. . . . Memory and hope for the future live in seminal texts such as Armenian Golgotha.”

—Keith Garebian, The Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“A powerful, moving account of the Armenian Genocide, a story that needs to be known, and is told here with a sweep of experience and wealth of detail that is as disturbing as it is irrefutable.”

—Sir Martin Gilbert

“Extraordinary. . . . This book will become a classic, both for its depiction of a much denied genocide and its humane and brilliant witness to what human beings can endure and overcome.”

—Robert Jay Lifton, author of The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide

“Witness literature of the highest order, to be put aside the great testimony from the Shoah. . . . Required reading for those who wish to comprehend the 20th century.”

—Robert Leiter, The Jewish Exponent

“An astonishing memoir. . . . An important primary document concerning the Armenian Genocide. . . . A major addition to the literature of witness and testimony.”

—Robert Melson, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In