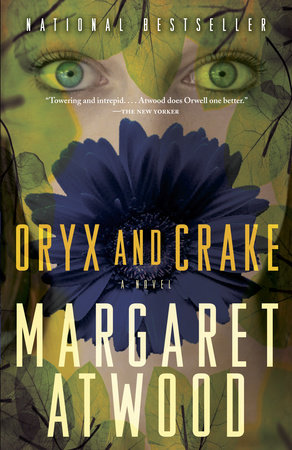

Oryx and Crake

By Margaret Atwood

By Margaret Atwood

By Margaret Atwood

By Margaret Atwood

By Margaret Atwood

Read by Campbell Scott

By Margaret Atwood

Read by Campbell Scott

Part of The MaddAddam Trilogy

Part of The MaddAddam Trilogy

Part of The MaddAddam Trilogy

Category: Literary Fiction | Science Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction | Science Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction | Science Fiction | Audiobooks

-

$18.00

Mar 30, 2004 | ISBN 9780385721677

-

Mar 30, 2004 | ISBN 9781400078981

-

May 06, 2003 | ISBN 9780739304082

630 Minutes

-

$18.00

Mar 30, 2004 | ISBN 9780385721677

-

Mar 30, 2004 | ISBN 9781400078981

-

May 06, 2003 | ISBN 9780739304082

630 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Praise

“Towering and intrepid. . . . Atwood does Orwell one better.” —The New Yorker

“Atwood has long since established herself as one of the best writers in English today, but Oryx and Crake may well be her best work yet. . . . Brilliant, provocative, sumptuous and downright terrifying.” —The Baltimore Sun

“Her shuddering post-apocalyptic vision of the world . . . summons up echoes of George Orwell, Anthony Burgess and Aldous Huxley. . . . Oryx and Crake [is] in the forefront of visionary fiction.” —The Seattle Times

“A book too marvelous to miss.” —The San Diego Union-Tribune

“Majestic. . . . Keeps us on the edges of our seats.” —The Washington Post

“A compelling futuristic vision. . . . Oryx and Crake carries itself with a refreshing lightness. . . . Its shrewd pacing neatly balances action and exposition. . . . What gives the book a deeper resonance is its humanity.” –Newsday

“[A] stunning new novel–possibly her best since The Handmaid’s Tale.” –Time Out New York

“A delightful amalgam for the sophisticated reader: her perfectly placed prose, poetic language and tongue-in-cheek tone are ubiquitous throughout, as if an enchanted nanny is telling one a dark bedtime story of alienation and ruin while lovingly stroking one’s head.” –Ms.

“Truly remarkable. . . . As fun as it is dark. . . . A feast of realism, science fiction, satire, elegy and then some. . . . Atwood has concocted here an all-too-possible vision. . . . [She is] a master.” –The News & Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina)

“A roll of dry, black, parodic laughter. . . . One of the year’s most surprising novels.” –The Economist

“Sublime. . . . Good, solid, Swiftian science fiction from a . . . literary artist par excellence.” –The Denver Post

“Dances with energy and sophisticated gallows humor. . . . [Atwood’s] wry wit makes dystopia fun.” –People

“A crackling read. . . . Atwood is one of the most impressively ambitious writers of our time.” –The Guardian

“Gorgeously written, full of eyeball-smacking images and riveting social and scientific commentary. . . . A cunning and engrossing book by one of the great masters of the form.” –The Buffalo News

“A powerful vision. . . . Very readable.” –The New York Times Book Review

“Brilliant, impossible to put down. . . . Atwood . . . is at once commanding and enchanting. Piercingly intelligent and piquantly witty, highly imaginative and unfailingly compassionate, she is a spoonful-of-sugar storyteller, concealing the strong and necessary medicine of her stinging social commentary within the balm of dazzlingly complicated and compelling characters and intricate and involving predicaments.” –The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Original and chilling. . . . Powerful, inventive, playful and difficult to resist.” –Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Brilliantly constructed. . . . Jimmy and Crake grip like characters out of Greek tragedy. . . . Atwood herself is one of our finest linguistic engineers. Her carefully calibrated sentences are formulated to hook and paralyse the reader.” –The Daily Telegraph

“Atwood does not disappoint.” –The Dallas Morning News

“Gripping. . . . Bursts with invention and mordant wit, none of which slows down its headlong pace. . . . Atwood is in sleek form. . . . [Her] prescience is unsettling.” –St. Petersburg Times

“Biting, black humor and absorbing storytelling. . . . Atwood entices.” –USA Today

“Compelling. . . . Packed with fascinating ideas. . . . Her most accessible book in years, a gripping, unadorned story.” –The Onion

“This superlatively gripping and remarkably imagined book joins The Handmaid’s Tale in the distinguished company of novels (The Time Machine, Brave New World and 1984) that look ahead to warn us about the results of human shortsightedness.” –The Times (London)

“Absorbing. . . . Atwood ahs not lost her touch for following the darker paths of speculative fiction–she easily creates a believable, contained future world.” –Seattle Weekly

“Engrossing. . . . A novel of ideas, narrated with an almost scientific dispassion and a caustic, distanced humor. The prose is fast and clean.” –Rocky Mountain News

“Riveting and thought-provoking. . . . Keen and cutting. . . . [Atwood] has grown into one of the most consistently imaginative and masterful fiction writers writing in English today.” –Richmond Times-Dispatch