TEACHING GUIDE

NOTE TO TEACHERS

Please click on the PDF link at the bottom of this page to download the Teacher’s Guide.

INTRODUCTION

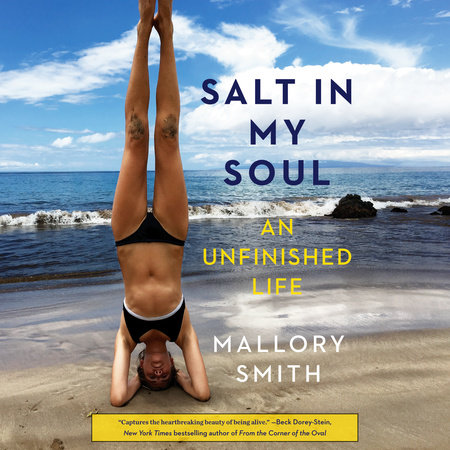

Mallory Smith’s Salt in My Soul begins with this declaration by the author’s 15-year-old self: “I am obsessed with salt water.” Over the span of the next 10 years, Mallory details in her journal just how essential salt is to her life. For even while her debilitating cystic fibrosis disrupts the flow of salt in and out of her cells, Mallory finds replenishment and healing in the ocean’s salt water. Her stirring memoir recounts the typical teen struggles one would expect to find in a young girl’s journal: issues with body image; the desire for independence mixed with the fear of growing up; the desire to take action in a world that is destroying its own environment. But Mallory’s journal is, at the same time, so much more. Alongside the entries on friends, family, and fun, the writer details the challenges of hospital treatments, the frustration that accompanies an invisible illness, and the determination to “Live Happy” despite and beyond her limitations.

Mallory’s journal entries are both lyrical and provocative. They are also a vivid depiction of a young woman finding her own voice. Declaring, “We are the writers of our own story” (p. 158), Mallory demonstrates to readers that writing is a powerful tool that can be used to develop a sense of one’s self and improve the world. Her memoir serves as an excellent mentor text for students exploring the critical connection between reading and writing.

The goal of this teacher’s guide is to facilitate the exploration by students of the reading-writing connection and to encourage them to “read like writers.” The reading strategies encourage students to analyze themes and craft, while the writing activities are inspired by Mallory’s topics and style. Teachers can assign activities as they see fit in order to empower student readers to become the writers of their own stories.

PRE-READING ACTIVITIES

1. To introduce one of the text’s main themes, invite students to think about the following question: What is the meaning of “legacy?” Once they’ve had time to consider the question, ask them to pair up and share their thoughts. Students will most likely discuss the idea of leaving something of value after death or something that is part of history. As a class, watch Diane Shader Smith’s TEDx Talk, “Salt in My Soul: Love, Loss, Legacy” at tiny.cc/SmithTEDx. The video starts with Mallory’s narration before transitioning to her mother’s talk. Diane explains that her purpose in making this video is “to talk about [Mallory’s] life and her legacy with the hope that hearing her story will inspire you to think about yours. Legacy means different things to different people. Some think it’s about a gift that you leave. Others think it’s about leaving something in people rather than for them. I think legacy is important because it gives those of us left behind something to cling to. . . . Mallory knew that she had a legacy that would impact others.” Afterwards, ask the class to discuss how the video supported, extended, or changed their initial thinking about legacy. Challenge students to keep Diane’s words in mind and think about their own legacies as they read Salt in My Soul.

2. Mallory hoped her journal would “offer insight for people living with, or loving someone with, chronic illness” (p. x). By publishing Salt in My Soul, Diane Shader Smith has furthered this effort to educate readers. Explain that Mallory’s mother had a similar purpose in mind with Mallory’s 65 Roses, the children’s book she wrote to educate Mallory’s elementary school classmates about her daughter’s invisible disease. The entire book can be found online at tiny.cc/65Roses by using the “Look Inside” feature. Read the book and view the illustrations together. Afterwards, pose these questions to the class and discuss:

● What insights can we gather about Mallory’s life from reading the children’s book?

● How does the tone and format of the children’s book support its purpose?

● In what ways might Salt in My Soul support the goals of Mallory and Diane?

3. Show students the NPR “Let’s Talk” video segment “How Superbugs Could Mean the End of Antibiotics” at tiny.cc/NPRSuperbugs. Afterwards, ask partners to define “superbug” in their own words. Students should understand that superbugs are a type of bacteria and that they are resistant to most antibiotics. Explain that in Salt in My Soul, Mallory’s condition is further complicated by the superbug B. cepacia. After discussing the video, direct students to read and identify important vocabulary words in the article “Scientists Modify Viruses with CRISPR to Create New Weapon Against Superbugs” at tiny.cc/CRISPR. Because the article contains complex scientific vocabulary, students might read with partners using the “Say Something” protocol (see tiny.cc/SaySomethingStrategy). With this strategy, students take turns reading a small segment of complex text, then pause to talk about it before moving on. In the CRISPR article, students might identify the terms pathogenic, bacteriophages, microbes, and microbiome. Explain to the class that these scientific terms will be central to understanding Mallory’s story in Salt in My Soul.

READING LIKE WRITERS

The following activities are designed to guide students in analyzing the author’s themes, craft, and structure. Students can use these activities to reflect on what Mallory sees as essential to life and how she tells her story.

Common Core Skills Focus

● Determine themes of a text and analyze their development

● Analyze how an author’s choices contribute to structure, meaning, tone, and aesthetic impact

1. Ask students to conduct a close reading of Mallory’s poem from November 10, 2008, which vividly depicts her CF pain, particularly when she needs hospital treatment (pp. 11–15). In the poem, Mallory uses imagery, repetition, and irony to describe her suffering. Students should first read independently, annotating in the margins any themes, figurative language, or other poetic devices they observe. Next, ask students to “turn and talk” with a classmate, sharing their annotations, explaining their thinking, and adding to their notes. Finally, partners can share their analysis with the whole class, annotating in color either by hand on the classroom whiteboard or digitally using Padlet.com or a shared Google Doc. Students should note red and white color imagery, the reappearance of the salt motif, and the repetition of “fine” to depict the ironic disparity between Mallory’s appearance versus her reality. As an extension, students might read the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s web page “Vascular Access Devices: PICCs and Ports,” which includes a video link showing a PICC line insertion into a CF patient: tiny.cc/CFFoundation. After reading the article, ask students:

· How does Mallory’s poem differ from the web page in terms of information and impact?

· Taken together, what can we better understand about a person living with cystic fibrosis?

2. Mallory says she wants to “hold on to the past” and that she doesn’t “ever want to forget anything” (p. 20). As a class, re-read pages 21–22 and discuss why these particular memories might be important to Mallory. Ask students, “What items and memories do you want to hold on to?” Challenge them to identify five or so items that best represent their current selves and the memories they’d want to experience in later years. Using boxes or manila envelopes, invite students to create individual time capsules holding these items. Students could include pictures, song lyrics, or keepsake items. Students might also write a letter to their future selves. Keep these capsules and return to students at the end of their senior year.

3. Mallory wishes “to wake up in the morning and take a deep, full breath” (p. 68). Due to her CF, breathing is a constant battle. Yet breathing has a metaphorical meaning for Mallory as well, as she constantly strives for balance. She writes, “Sometimes acceptance and ease, rather than force and struggle, are the keys to survival” (p. 183). Focus on breathing and balance with students by trying out a “mindfulness moment,” a classroom practice that is research-based and taking hold in many schools. Before the start of class, greet students quietly, encouraging them to put away their digital devices and take their seats in a classroom that is dimmed, peaceful, and quiet. These directions may be posted on chart paper or the whiteboard. Direct students in a slow, purposeful breathing exercise and focus attention on breathing or on an ambient sound, such as tranquil music or hallway noise. End the mindfulness moment verbally or with a singing bowl and transition to the day’s lesson. The idea is to help students move from the noise and chatter of their day to free their minds and improve their focus. More on classroom mindfulness can be found at tiny.cc/MindfulnessInHS.

4. Using the Juicy Sentence strategy, unpack and analyze with the class Mallory’s journal entry from January 20, 2011. Juicy Sentence analysis (tiny.cc/JuicySentence), developed by Dr. Lily Wong Filmore, reveals the impact of writer’s craft on meaning. These sentences have high informational density, are “chunkable,” and contain multiple phrases or clauses. Read aloud for the class the sentence starting with “For the smell of the water” and ending with “as you drive along in the sunshine” (p. 45). Decide with the class where to divide the phrases and copy them on the whiteboard or screen, using color to differentiate “chunks.” Next to each phrase, note sentence features and vocabulary. Model the first segment, then direct partners to complete the task. For example, “For the smell of the water” is a double prepositional phrase, including an element Mallory has repeatedly said is important to her (water). Next, ask the class to identify patterns. Students will most likely notice that each piece is dependent—no portion can stand alone; in fact, the entire sentence is a fragment, as are the next couple. Such writing opens itself to questioning: “Why did Mallory write an entry full of fragments this time?” “How does she use authorial choice here to capture a mood?” “When is it acceptable for writers to use fragments?” Discuss how this structure is called “cataloging” by experienced writers and is used for rhetorical effect. For Mallory, she wishes to capture the feeling of freedom and potential she experiences in Hawaii. To extend the lesson, students can try their own hand at cataloging, like Mallory, why they “actually like life.”

5. Mallory is passionate about “the intersection between human societies and the environment, and sustainable development and agriculture” (p. 64). For students to understand Mallory’s interest, facilitate a jigsaw-read of “Global Goals” from “Goalkeepers,” which was started by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Global goals include no poverty, zero world hunger, good health and well-being, quality education, gender equality, and clean water and sanitation. Provide each student a number one through six, and direct the ones to review goal one, the twos to review goal two, and so on. The website review should take about 20 minutes. Groups can access the Global Goals’ descriptions, infographics, and research at tiny.cc/Goalkeepers. After groups decide on main talking points, students should reconfigure into home groups, in which each of the six numbers is represented. Groupmates should summarize the discussion of their goal and record bulleted notes on a graphic organizer. After students have completed their note-taking, conduct a large group discussion about the goals and why they are significant today.

6. Mallory’s senior reflection project at Stanford University was a podcast inspired by one of her journal entries (pp. 100–103). In her podcast “Biome,” Mallory compares the destructive colonization of Hawaii by Westerners to the destructive colonization of her lungs by the B. cepacia superbug. Ask students to listen to the podcast at

tiny.cc/BiomePodcast and make note of any insightful or aesthetically pleasing phrases or sentences. Students can rewind, re-listen, and take notes at their own pace. Next, ask students to conduct a close reading of the podcast using the SPACECAT rhetorical analysis protocol. Students identify and analyze specific words, phrases, and sentences in the podcast aligned to speaker, purpose, audience, context, exigence, choices, appeals, and tone. Partners can compare and share their thinking before discussing as a whole class. Look for students to include in their analysis how Mallory employs all the traditional appeals (ethos, pathos, and logos) to support her comparison of seemingly very different events. Students should also note the shifts in topic and tone between the history of Hawaii and Mallory’s personal history with cystic fibrosis. With this strategy, students will think critically and discuss meaningfully the argument and craft Mallory uses, ultimately determining author’s purpose and how it is supported by authorial choice. In the large group discussion, remind students of the purpose Mallory establishes for her writing at the beginning of the text: “My hope is that my writing will offer insight for people living with, or loving someone with, chronic illness” (p. x). Ask the class: How do the choices made in Mallory’s podcast support her stated purpose for her writing?

TEXT-DEPENDENT QUESTIONS

These questions ask students to re-read specific sections of text and can be used for independent written responses and/or collaborative discussion.

Part One

1. The author begins the book with a metaphor about “the chains that bind” her (p. ix). After reading the first two pages of her introduction, describe why Mallory might have chosen this figurative language. Consider what she says about cystic fibrosis as well as her audience and her reasons for writing.

2. Mallory uses additional figurative language throughout the introduction. Discuss the meaning of either her erosion (p. xi) or earthquake (p. xii) similes. What impact does this language choice make on the reader? How does it support her stated writing goals?

3. Explain what Mallory means when she says, “It’s a blessing and a curse not to look sick” (p. xiv).

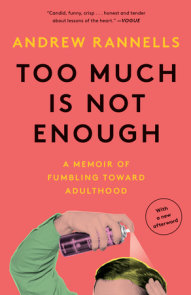

4. In the first entry of her memoir, Mallory says, “I am obsessed with salt water” (p. 5). How might her love of salt water relate to her description of cystic fibrosis (p. x)? How does this opening connect to the book’s title and cover art?

5. Why does the May 6, 2008 entry change format? Why might Mallory have chosen to pen this entry as a letter?

6. In an entry about volleyball, the author claims, “What we need is to replace our desire to be perfect with a desire to do everything to the best of our abilities” and “We should only be satisfied with losing if we’ve given it our all” (pp. 9–10). How does this entry provide insight into Mallory’s life philosophy?

7. In her September 5, 2009 entry, Mallory discusses her feelings about being taller than most of her friends and classmates. What previously introduced themes does she touch on here? Discuss possible interpretations of “I would never be breaking hearts” (p. 17).

8. What are Mallory’s specific concerns with time? Are these concerns similar for other teens? Explain.

9. Why does the author choose the word “repulsive” when she discusses her relationship with food (p. 19)? What pattern is developing in Mallory’s self-image? Is this an understandable pattern? Why or why not?

10. When Mallory writes about memories she wants to hold onto, she includes her hospitalizations in the same sentence as trips and adventure with friends (p. 21). Discuss the juxtaposition here. What does this writing choice illuminate about Mallory’s life?

11. Four days after Mallory writes about wanting independence (p. 20), she admits that she is “a CHILD” dependent on her parents for the smallest things (p. 21). What does Mallory’s journal reveal in including these entries so close together?

12. Mallory’s journal entry about applying to Stanford reveals multiple considerations she must keep in mind, some typical of any high school senior, some not at all typical (p. 23). Discuss the complexities of Mallory’s college selection.

13. In the summer of 2010, Mallory had just graduated high school and was looking forward to starting her freshman year at Stanford (pp. 37–40). What do these entries reveal? In what ways is Mallory dealing with typical coming-of-age issues? What additional challenges does she face?

Part Two

1. Why does Mallory worry about drinking in college (p. 53)? What does she fear if she does drink? What does she fear if she doesn’t?

2. Mallory says, “I feel like I’m going to fade away and be forgotten” (p. 54). How does this fear align with earlier entries on remembering and time? How might Mallory’s journal address this fear, both for her as the writer and for us as readers?

3. What does Mallory mean when she says, “I’m living a double life” (p. 59)? Why does she refer to herself in the third person in this section, and how does that choice illustrate her point?

4. After a college instructor fails to accommodate Mallory’s necessary absences, she advocates for herself in writing via email (pp. 61–63). Mallory’s mother offers to send her daughter legal language and suggests that her daughter contact her medical team. How might Mallory’s relationship with her mother be described here? Why doesn’t Mallory’s mother call the medical team for Mallory? In the big picture, what is she encouraging Mallory to do? How difficult might this be for Diane? In what ways is Mallory developing her voice?

5. During one of her many hospital stays, Mallory composes an “I want list” (pp. 68–69). Her writing shifts format at the end of this entry and instead of an “I want” statement, it ends with “I am happy today.” Why does Mallory make this shift here? How and why is her concept of happiness evolving?

6. After attending a friend’s funeral, Mallory contemplates how life will be for her family once she dies. She worries, “It makes me heartsick to think about what I would leave behind if I passed on” (p. 72). What does Mallory think she will “leave behind”? Is she building a legacy, as she hoped early on? What role might her writing play?

7. Mallory says of herself and fellow CF patients, “We had been pursuing our dreams with the same tenacity, suffering similar accelerating disease progression as a result” (p. 90). Explain the irony in this statement.

8. Discuss the extended metaphor Mallory uses to describe the struggle faced by her and other CF patients (p. 90). Include specific diction that supports this metaphor.

9. Describe Mallory’s tone in her entry about the sea turtle dream (p. 99). Provide evidence.

10. Mallory compares two seemingly different topics: her nine-year-old rebellion with breathing exercises and the concept of sustainability (pp. 100–102). What specific words and lines serve to align these two ideas? What is the impact on the reader? How does Mallory give insight into her disease as well as into one of her passions?

Part Three

1. How can Mallory’s tone be described in her October 16, 2015 journal entry? How does the timing play a part in creating this tone? What does she come to realize about herself here?

2. Discuss the recurring theme in Mallory’s reflection, “We have to blame the disease, the disease that tries to define us” (p. 133).

3. Why might Mallory’s November 6, 2015 entry mark a distinct shift in format, pronoun usage, and voice?

4. Discuss the insights Mallory voices about her depression (pp. 153–154; 173–174). How might her journal writing here contribute to her realizations?

Parts Four – Six

1. Describe Mallory’s relationship towards her mother, as detailed on pages 165–166. How have Mallory’s feelings towards Diane developed since adolescence?

2. Discuss the impact Kalanithi’s book has on Mallory (p. 186). How do Mallory’s lives as a reader and a writer intersect here?

3. Towards the end of her life, Mallory writes, “I realize I want to write my story” (p. 202). What might be ironic about this desire at this time? Consider multiple points of irony.

4. What theme is developed in Mallory’s entry on November 12, 2016 (pp. 229–231)?

WRITING TO REFLECT

These activities encourage students to produce personal writing inspired by a mentor text. Students reflect on what is essential to their lives and explore how they might tell their own stories.

Common Core Skills Focus

● Write routinely over extended and shorter time frames for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences

● Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects to reflect or answer a question

1. As students read Mallory’s personal journal entries, invite them to stop and reflect on some of the same topics. Explain to students that they will have the opportunity to select entries to include in a multimedia memoir. Following are personal writing prompts that align with specific pages in the text.

· At the beginning of her book, Mallory outlines four reasons why she is a reader (p. 6). What and why do you read? How do you see yourself as a reader?

· Mallory explains why she writes and what she hopes to accomplish with her writing (p. ix, 7). What are some types of writing you do, and why? How do you see yourself as a writer?

· Re-read what Mallory says about non-milestone moments such as biking by a tree as a leaf falls (p. 6). Write about an “insignificant” moment in your life and why it ended up taking on “distinct meaning.”

· Mallory says that her household is “all about food” (p. 7). What is your household “all about”?

· Mallory writes about books and movies that made her cry (p. 16). Write about a book or movie that made you sad.

· Mallory says she pictures herself in high school forever and is unsure about who she is and about “growing up” (p. 18). Are you ready for life after high school? Explain.

· Mallory tries to calm her anxiety by considering the things that make her happy, such as driving with the top down, listening to “an amazing song,” laughing, and eating a healthy meal (p. 19). What makes you happy? Choose one or more specifics and explain why.

· While discussing her fears about growing up, Mallory says she wants “to remember every little detail” (p. 21). What specific things do you want to remember about your childhood?

· In college, Mallory finds herself having to defend her health-related absences and request necessary accommodations (pp. 60–62). Describe a time you self-advocated or wish you had.

· Mallory lists “good things that happened today” (p. 65). Re-read this excerpt and make your own numbered list.

· While back in the hospital, Mallory reflects on what she wants in life (pp. 68–69). Re-read this section then make your own “I want list,” using a format similar to Mallory’s.

· At age 20, Mallory considers how her “wishes have evolved” (pp. 70–71). How and why have your own wishes changed as you’ve become older?

· In Hawaii, Mallory experiences a sense of health and restfulness (p. 72). Write about a place that brings you peace and calm, a place where you feel like you. Consider specific places like buildings or cities, but also abstract places such as nature.

· While reflecting on her childhood as well as the concept of environmental responsibility, Mallory laments, “We don’t accept that what we do now will hurt us later” (p. 101). How do you see this theory playing out today?

· In an effort to avoid feeling aimless and find happiness despite serious health issues, Mallory replaces New Year’s resolutions with “North Stars” (p. 146). What habits and processes provide you direction rather than achievement? Compose a list of your own North Stars.

2. Create a class “crowdsourced” poem based on poet George Ella Lyon’s “Where I’m From” poem. Explain to students that writing about personal, concrete details helps writers and their audiences reflect and connect, just as Mallory does when she writes about her struggle to breathe (p. 11). After reading Mallory’s poem, ask students to read and listen to the original “Where I’m From” poem at tiny.cc/WhereImFrom. Using this format and its sentence-starters as a template, encourage students to write several verses based on their own lives. Next, read with the class the NPR crowdsourced poem that combines multiple writers’ voices. Create a similar crowdsourced poem from the students’ work and share via the class website.

3. Ask students to pen an authentic college essay. Explain that, as Mallory declares, writing a college essay is hard because it means writing “about who you are” (p. 18). Read and discuss with students the Princeton Review’s article “Crafting an Unforgettable College Essay” at tiny.cc/CollegeEssay. Review the expert tips and emphasize the article’s claim that “this is your chance to tell your story.” Next, read the article’s sample student essay, unpacking with students what makes this writing sample stand out. In the discussion, ask students to explain the article’s claims that “it’s more about the voice than anything else” and “you can think of the essay as the soul of the application.” Ask the class, “What is the relationship between a person’s ‘voice’ and ‘soul’?” Reflecting on the title of Mallory’s memoir, why does Mallory feel salt is an essential part of her soul? How does writing about her beliefs, hopes, and experience reveal who she is? Finally, challenge students to try their hand at drafting a college admission’s essay, following the tips outlined in the article and using the sample essay and Mallory’s text for inspiration.

4. On several occasions, Mallory uses her writing to argue or persuade. Together as a class, re-read one of these excerpts and analyze Mallory’s argument using the CER protocol (claim, evidence, reasoning). For instance, in her correspondence to a college lecturer (pp. 60–62), Mallory’s claim is that she should be able to make up medical absences. For evidence, she recalls past experiences and suggests several avenues to make up work. She details hospitalizations in her reasoning. Students can annotate the text on the white board or using a shared digital tool such as a Google Doc. Next, ask students to identify examples of classic rhetorical strategies (ethos, pathos, logos) in Mallory’s argument. Add these to the class annotations. For example, Mallory employs logic to point out that not allowing make-up work in this particular language class equates to not being able to take any Stanford language class. Discuss as a class the impact of Mallory’s reasoning and rhetorical style. Finally, challenge students to write their own CER essay and advocate in writing for one of Mallory’s topics of interest, such as sustainable living, healthy eating, the opioid crisis, or patient rights. For more information about CER writing, see tiny.cc/CERWriting.

SYNTHESIZING ESSAY AND DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

These after-reading questions can be used to initiate discussions in small or whole groups or as essay prompts. Ask students in both situations to explain or elaborate on their ideas by providing details or quotes from the text.

1. Mallory wants to “Live Happy,” but what this means to her changes over the course of her life. Trace this theme throughout the 10-year span of Mallory’s journal.

2. Mallory writes about her mother throughout the pages of her memoir. How can their relationship be described? What role does Diane play in shaping her daughter’s voice and legacy?

3. Hawaii holds a special place in Mallory’s life. Why? Taken as a whole, what patterns emerge in the Hawaii entries? What themes develop throughout these passages?

4. Mallory hoped her journal would “offer insight for people living with or loving someone with chronic illness.” Does her memoir offer such insight? What are the main takeaways for readers of Salt in My Soul?

5. Throughout her journal, Mallory repeatedly emphasizes the significance of writing. What role does writing play for Mallory, both during her life and after her passing?

TELLING OUR STORIES

Multimedia assignments enable students to synthesize their analysis and reflections and select an avenue for publishing their writing.

Common Core Skills Focus

● Strengthen writing by revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach

● Use technology to produce, publish, and update individual or shared writing products

In her journal, Mallory summarizes writer Anne Lamott: “To become a better writer, you have to write more. Writing reveals the story because you have to write to figure out what you’re writing about” (p. 143). Now that students have read Mallory’s memoir, ask them to look back at their writing to select pieces they would like to develop more and to produce a multimedia memoir that tells their story. Just as Mallory believed salt to be essential to living a happy life, student writers might select a person, place, or object elemental in their life and make that topic the basis for their project and the inspiration for their title. For instance, students might extend their journal entry about a place they find significant or the one about a specific song or food that makes them happy. The multimedia memoir should answer the question “Who, what, or where is elemental to my life?”

Possible formats for the multimedia memoir might include one or more of the following:

● A podcast inspired by Mallory’s autobiography: Using free audio recording and editing software such as Audacity (www.audacityteam.org) or Gravity (tiny.cc/GravityMediaEditor), students produce a personal podcast based on one of their journal entries. The script might be informative or even a comparison-contrast format like Mallory’s comparison between the colonization of Hawaii and the colonization of her lungs.

● A single-taping TED Talk–type video complete with staging, lighting, and scripted narration aided by cue cards: In the talk, students might pull together portions of one or more of their journal entries as they answer “Who, what, or where is elemental to my life?” Students can use cell phones or tablets to record their talks. Later, share the videos in an auditorium setting with classmates as the audience.

● A digital story using iMovie or Windows Movie Maker: Students can appear on screen reading their “Where I’m From” poem aloud while images, family photos, or videos play in the background. Or, students might choose to extend an entry about a person who is important to them by mixing an interview with narration and still photos. Digital stories are easily created on student laptops.

● An interactive webpage that combines multiple digital features to tell a story: With Adobe Spark (spark.adobe.com), students can combine text, social graphics, video, and audio to showcase multiple writing samples. The webpage might include a tab for the “Where I’m From” poem, a tab or two for journal entries, and tabs for photos, songs, or other media important to the writer and addressing the question “Who, what, or where is elemental to my life?”

ABOUT THIS GUIDE’S WRITER

Laura Reis Mayer is a High School Instructional Coach and National Board Certified Teacher in Asheville, North Carolina. She has taught middle, high school, and college English, speech, drama, and literacy. As consultant to various national and regional organizations and districts, she develops and facilitates curriculums and conferences on college and career ready standards, teacher leadership, best practices, and National Board Certification. She is the author of 15 Signet Classics Edition Teacher’s Guides.

ABOUT THIS GUIDE’S EDITOR

Jeanne M. McGlinn, Professor of Education Emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Asheville, has taught and written extensively about adolescent literature and methods of teaching literature and writing. She is the author and editor of numerous teaching guides and a critical book on historical fiction for Scarecrow Press Young Adult Writers series.

×

Become a Member

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In