Can you tell us how you became a writer?

I was a psychologist in private practice for twenty-five years. For fun, I once wrote an unsolicited column for Facts and Arguments in The Globe and Mail and just faxed it in one day. To my surprise it was published. An editor at Chatelaine magazine happened to read the column and invited me to be their psychological advice columnist. That was the birth of my journalism career.

My creative writing career was equally serendipitous. I’m a bit of an Irish storyteller, so once, at a party, I told a childhood tale about how I’d worked full time from the age of four delivering drugs with a black delivery car driver, and how we’d been trapped in the snow overnight. Someone at the party told me to write the story and send it to a publisher. So I quickly wrote up the tale and then mailed it in on a Friday. On the following Monday I received an advance cheque in the mail with a yellow Post-it attached that said "finish it." Not wanting to give back the cheque, I finished the book. That is how my childhood memoir, Too Close to the Falls, was hatched. It was on the bestsellers list for seventy-two weeks, so that helped me to decide I must be a writer.

What inspired you to write this particular book? Is there a story about the writing of this novel that begs to be told?

Twenty-five years ago I wrote a Ph.D. thesis titled Darwin’s Influence on Freud. Over the many years I spent in the library reading their letters and works, I got to know Darwin and Freud fairly well. I noticed personal quirks and inconsistencies that I believed were subtly reflected in their theories. My mind was full of the sort of details you can put in a novel but never in a Ph.D. thesis.

For example, Freud proposed the seduction theory in 1895. Some of Freud’s hysterical patients reported having had incestuous relations with their fathers in childhood. Freud then postulated that these incestuous (what he called “seduction”) relationships resulted in the adult onset of hysteria. Then suddenly — two years later, in 1897 — Freud retracted the seduction theory saying he had made a mistake. He said he finally figured out that it was the patient’s fantasy that she had been seduced by her father. Freud said he mistook the patient’s fantasy, based on longing for the father, for a reality.

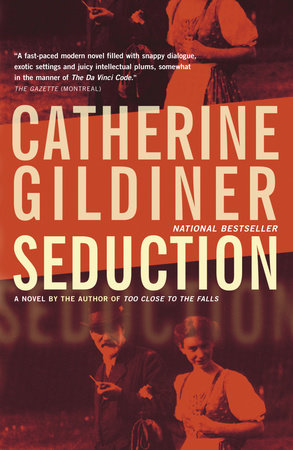

No scholar has ever really known why Freud changed his mind, and critics have raved on for years about it, but the truth is no one really knows. My novel, Seduction, is about what I imagine happened in that two year time period to make Freud change his mind.

What is it that you’re exploring in this book?

I wrote Seduction on two levels. On level one it is a simple thriller. Who threatens the Freudian archivist and why?

The second level is an exploration of Freud’s early work and Darwin’s later work. Freud was a biologist until he was over forty and then he turned to psychology. Darwin, on the other hand, was a biologist until his later years and then he became a psychologist. I wanted to explore in what way these two men are mysteriously related. Along the way I explore various secrets that both of them could be covering up.

I have always been interested in the history of science and the interaction between theory, personality and the social context of the theorist. The idea of objective knowledge has always seemed to me to be an oxymoron.

I am hoping that Seduction will give its readers some new information about Darwin and Freud, while simultaneously showing how complicated it is to have ideas accepted. Most importantly, I want people to have a good time reading a page-turning yarn.

Who is your favourite character in this book, and why?

I think Kate, the female detective — or in this case, Freudian dick — is my favourite. The opening line of Seduction is Kate saying, “It’s really embarrassing to admit, but I forget why I killed my husband.” Kate has been in jail for a decade and read Freud while in her cell in order to try to understand why she killed her husband. She, like me, is a philosopher of science and has learned something about Freud. I, however, have not killed my husband (yet!). She is then hired by a psychological association to find out who is threatening the current Freudian archivist. I identify with Kate in her overestimation of rational behaviour and her underestimation of emotional understanding.

In fiction, every character is in some way an extension of the author, or the author would have no understanding of what makes the character tick. There is a section of me in each character, but the book is written in the first person. In order to do that, I had to get into Kate’s skin. She travelled with me like a Siamese twin until the book was finished.

Are there any tips you would give a book club to better navigate their discussion of your book?

All of the theories presented in the book have validity. There is no right or wrong one. I tried not to present suspects but instead people who had reasons for their beliefs — all of which are justifiable.

The other thing I would say is try not to commit the sin of presentism. Darwin and Freud were writing in the Victorian era when no one believed in the unconscious or evolution. Try to place yourself in the era before you judge their actions.

In terms of approaching the book you might want to look at the parallels between the lives Kate, the detective, is investigating and the life she herself has led.

Do you have a favourite story to tell about being interviewed about your book?

I haven’t been interviewed about the book yet, as it is just coming out. But when I was in London doing research for it, I asked the concierge in my hotel for directions to Freud’s home. He said he would look it up and call me. When he rang up he said, “I have some distressing news. Mr. Freud, the gentleman you are going to visit, seems to have passed away.” When I told the cab driver this tale, while he was driving me to Freud’s home, he said in a thick Cockney accent, “Ya see mate? That’s what happens when you do away with the O levels.”

What question are you never asked in interviews but wish you were?

I’m really interested in the creative process. What makes fiction work? How much of it is unconscious symbol, in order to make it universally interesting? In interviews about my memoir, I was concerned with the difference between truth, unconscious reality and memory. People would often ask, “Is this true?” I would have liked to explore the relationship between memory and reality or truth. Isn’t memory a compilation of unconscious symbols? Is that truth? This is of course my preoccupation as a writer, and it is no wonder no reader has asked me about it.

Has a review or profile ever changed your perspective on your work?

I remember when my first review came out for my first book, the memoir Too Close to the Falls. A friend called me and said, “You are reviewed in Toronto Life magazine and it says your book is ‘hilarious.’” I was horrified. I thought the reviewer meant that it was laughable, as in “laughed at not with,” a phrase that haunts me from Catholic school. When I dashed to the store and read the review in Mac’s Milk, the proprietor read it with me and said, “You must be a funny writer.” That was the first time I ever thought of my book as humorous. I learned the book was humorous and that I was a humorous writer from the review.

I was also shocked when the reviews referred to my childhood as unusual. I thought I had a totally normal childhood. However, I discovered that working full-time at four and having a mother that never made a meal was considered unusual. It seemed normal to me because I lived and enjoyed it. If you are happy, your parents never say an unkind word to you or to each other, you aren’t poor and there are no wars, you have no idea that your childhood is strange.

Which authors have been most influential to your own writing?

I think we are most influenced when we are young. I know I was. As a teenager I read George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss and felt like Maggie and I were peas in a pod. Eliot’s Middlemarch was right up my alley, with Dorothea initially believing intellect was above social justice. The book is about her learning to combine the two.

The Bronte sisters really moved me, and in a way Jackie, the detective and quasi-love-interest of Seduction, who has spent most of his life in jail and then come out and bettered himself, is a modern-day Heathcliff (Wuthering Heights). Kate, the heroine of Seduction, is a Catherine-like figure. Like Heathcliff and Catherine, Jackie and Kate can’t be together, nor can they part.

I have read all of Dickens and still see characters on the street that I think resemble some of his finest creations. When I was young, my mother read me Dickens, and then each night, since I was an only child, I would “talk” to the characters as though they were playmates. As a teenager, Sidney Carton (A Tale of Two Cities) was my fist crush. I have always been a lover of character development and I can only thank Dickens for that.

If you weren’t writing, what would you want to be doing for a living? What are some of your other passions in life?

Psychology is still a passion of mine, and although I don’t want to practice again, I still want to write in the area. I would also like academia. I’d love to write books and articles on various topics in the philosophy of science. I also have a flair for business and could see myself doing that, as I was also a business consultant when I was a psychologist.

I love competitive sports. I am on a masters rowing squad and we have competed for 11 years on a racing team. We even went to the Worlds a few years ago. I also windsurf whenever I can and have on rare occasion raced. I enjoy hiking and the outdoor world.

If you could have written one book in history, what book would that be?

The Interpretation of Dreams — but Freud beat me to it.