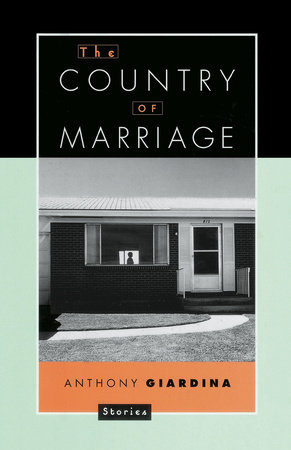

A Conversation with Anthony Giardina

Q: What you’re talking about in RECENT HISTORY are men and how they deal with intimacy. How is being a man today different from previous generations?

A: One of the trickiest things in my life has been tracking my own progress against my father’s at a similar time in his life. When my father was fifty, which is what I am, he was building my mother her dream house; he was forcibly lifting the two of them, and their children, up a class. Their relationship may not have been great, but maybe it didn’t matter so much. They were a corporation, a couple in sync with their times. At 50, I’m not building my wife her dream house. We tend to talk much more about our relationship, about the mental health of our kids; we may want more on the physical plane, but that’s never the number one priority.

No thinking person, in a relationship, can miss the demand that exists today for more intimacy, more emotional honesty and nakedness. We’re asked now to meet one another, sexually and emotionally, in a way our parents weren’t asked to, at least not by the culture in which they lived. So I wanted, in this novel, to look at a couple who are really suited to each other in most ways, yet who harbor, on the male side, a potentially crippling secret.

Q: Does RECENT HISTORY posit that all men, straight and gay, have a homosexual side to their personalities?

A: I don’t think all men have a homosexual side to them, no. But I think the labels "straight" and "gay" are about as useful in describing men’s internal lives as the labels "conservative" and "liberal" are in describing the politics of the average American. This is not a comfortable thing for men to discuss; in fact, it’s hardly discussed at all. At dinner parties I’ve been to, women seem to feel pretty free to let on that they’ve experimented in their youths with other women, but when the discussion turns to the men, the guys clam up. In fact, when I describe the plot of RECENT HISTORY to my male friends, a curious silence ensues.

A: Then how do you think male readers will react?

Q: Not to be too pretentious about it, this is the ur-history of men I’m writing about here, the suppressed history, the things I imagine a lot men have felt but have had to suppress because it’s never been an acceptable part of the campaign biography. I imagine men will read this book on subways with a brown paper bag wrapped on the cover, but they won’t be able to put it down.

Q: How does a straight father of two decide to tackle such a controversial subject?

A: The novel came out of a letter I read in the Dallas Sunday News, five years ago. The son of a gay father wrote in to defend his father against what I assume were some inflammatory anti-gay letters that had already come into the newspaper. What struck me about that letter was its tone, how difficult it must have been to write—the fact that a straight man was standing up within an extremely conservative community to defend his father’s choice. But, look, it’s exactly a married father of two who should be writing a book like this. A gay man is not going to write it because he’s probably going to (quite naturally) want the main character to come out. It’s only when you’re writing from within the mainstream that you can summon the appropriate tension for a story like this.

Q: Can you give an example of what you mean?

A: Last New Year’s Day, I found myself standing in the corner of a kitchen at a party with four or five guys—all straight, married, fathers—and one of us started talking about an experience he’d had as a teenager when his family had moved to Buenos Aires. He was followed by a man one night, and though he was frightened by it, he also found himself excited, and it was this latter emotion that had trailed him for the subsequent 35 years. One by one, the others of us joined in. We’d all had one haunting, unexplored foray into the other side of sexuality. And as I stood there listening, I understood that what made this discussion fascinating was the level of fear underpinning it. In each of the voices was a heightened sense of: how much am I exposing myself here? How far am I stepping out of the proscribed circle of acceptable male heterosexuality? It’s not that a gay writer couldn’t capture that level of tension, but I wonder how many gay male writers would be interested in the dilemma of the straight male world trying to figure itself out. Here I am using those labels "straight" and "gay," and I don’t mean to, but we haven’t evolved useful alternatives. Maybe this book represents a modest attempt to move that discussion forward. In ten years, I hope we’ve added some new words to the vocabulary of male sexuality, or better yet, quit characterizing altogether.

Q: What ARE men thinking about when they look at another man?

A: Any number of things, though the thoughts aren’t necessarily sexual. Yet I’m always astonished by the thoughts my therapist friends tell me their patients say in therapy, especially when the patients are free-associating. It’s wild. Sexual fantasies involving the male therapist from men who are leading authentic heterosexual lives. But it’s all part of the huge rush that forms each moment of our waking lives. I once wrote in an essay that "99% of life takes place in a territory to which no one has yet given a name; it’s a space created by two individuals, while they are looking at each other and not speaking." That’s the territory I’ve always believed fiction should be dedicated to exploring. There are lots of things fiction writers are doing that historians and sociologists can do just as well. But the secret life of our times, that’s the exclusive province of fiction.