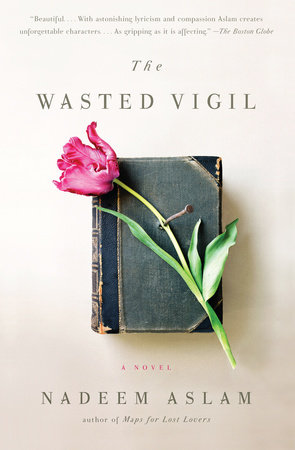

The Wasted Vigil

By Nadeem Aslam

By Nadeem Aslam

By Nadeem Aslam

By Nadeem Aslam

Part of Vintage International

Category: Literary Fiction | Military Fiction

Category: Literary Fiction | Military Fiction

-

$23.00

Sep 08, 2009 | ISBN 9780307388742

-

Sep 09, 2008 | ISBN 9780307270269

-

$23.00

Sep 08, 2009 | ISBN 9780307388742

-

Sep 09, 2008 | ISBN 9780307270269

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Praise

“Harrowing yet beautiful. . . . With astonishing lyricism and compassion, Aslam creates unforgettable characters. . . . As gripping as it is affecting.”

—Boston Globe

“Extraordinary. . . . Aslam’s determination to gaze resolutely at the darkest side of our many cold and hot wars is what gives The Wasted Vigil its depth and power.”

—Pankaj Mishra, The New York Review of Books

“Unflinching. . . . [Aslam] seeks to reveal the psyche not just of one rural village or one immigrant community but of Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States and Afghanistan. The revelations throughout are artful.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Heartbreaking. . . . Important. . . . This novel deserves as wide an audience as the recent bestseller The Kite Runner.”

—The Oregonian

“The power of Aslam’s novel lives in the explosive adjacency of brutality and love, the poison of fanaticism diluted by the perfume of Persian lilacs.”

—O, The Oprah magazine

“Unforgettable. . . . Tragic and beautifully written. Aslam is a major writer.”

—A. S. Byatt

“Even more beautifully written than his much-acclaimed Maps for Lost Lovers.”

—Financial Times

“Remarkable for being at once topical and timeless—a complex and layered vision of contemporary Afghanistan. . . . Like Michael Ondaatje before him, Aslam has a way of breathing life into larger historical and political backdrops with sensual details and lush interior lives. The Wasted Vigil shimmers with moments of poetic beauty and seems destined, like The English Patient, to become a classic of modern, globalized literature.”

—Time Out New York

“A searing, multifaceted novel. . . . You might think that there is a particular specter haunting Afghanistan in these early years of the 21st century—the Taliban—but in Aslam’s penetrating view, there are multiple forces at work there.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Both lyrical and sharp. . . . It’s a bold task to attempt to point out the similarities between a Muslim fundamentalist’s zeal and an American CIA agent’s righteous view of his job, yet, amid a sweeping story about love, Aslam does exactly this with considerable poise.”

—The Christian Science Monitor

“Stunning. . . . In this epic of a novel, Nadeem Aslam’s narrative takes in the explosive realities of Afghanistan. He navigates this minefield with sharp reflexes and a rare poise. . . . Beautiful and brutal.”

—Mohammed Hanif, Independent (UK)

“Ambitious and luminous. . . . Reminds us that fiction can do things that mere reportage can’t. . . . Aslam does not simply appropriate a few headlines for easy currency. He has immersed himself in a country and a culture and drawn upon art, mythology and history to provide an involving and morally complex tale of the ruthless betrayals and the queasy compromises that are made by nations and individuals alike.”

—The Sunday Times (London)

“At its core, The Wasted Vigil is not a book about Afghanistan, but of love. . . . Aslam’s Afghanistan is both beautiful and fraught with danger, with stunning images and landscapes that bring his characters’ world to life, all of it rich with symbolism.”

—Charleston City Paper

“What the reader finds, in Aslam’s exquisitely written, gripping narrative, is that although war destroys lives and shatters families, and people are capable of the greatest brutality, love and humanity still survive.”

—Daily Mail (London)

“The softly gleaming beauty of Aslam’s prose is immediately reminiscent of Michael Ondaatje, and the moral clarity of his concerns heralds a brave new voice in the mold of Salman Rushdie.”

—St. Petersburg Times

“Spellbinding—a beautifully drawn web of the fragile connections of trust, misunderstanding, memory, sacrifice, and, against the odds, love, that people who have lost everything else in the deadly stupidity of war must live and die by. Nadeem Aslam is a master of words and arresting images. . . . The sheer, astonishing loveliness of this novel’s language fills the reader with hope that the transformative power of beauty can, somehow, still save the day.”

—The Times (London)

“Piercing. . . . There isn’t enough beauty in the world, but isn’t it true that a work of art can be too beautiful? Aren’t there depths of suffering and barbarity that demand that the writer rein in the verbal glory? Nadeem Aslam doesn’t think so, as he proves with his astonishing new novel.”

—The Observer (London)

“Enthralling. . . . The Wasted Vigil is a delicate work of art, a tapestry, which connects people in a mesmerizing story of loss, memory and pain, but where humanity and love and its fragility emerge out of the debris.”

—New Statesman (London)