Author Q&A

A Conversation with Patrick Gale

Lillian Dean lives in Los Angeles and has written two screenplays

and a whole bunch of book reviews.

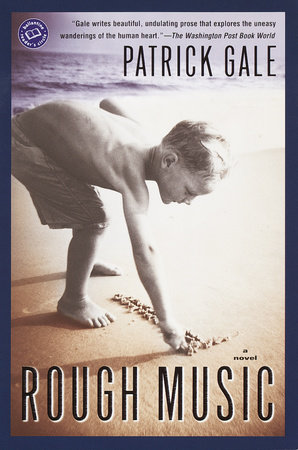

I got to know English novelist Patrick Gale in that ineffably modern

way: via e-mail. After I reviewed Rough Music for Hero magazine, I

was assigned to interview Patrick for the next issue. I sent him a series

of e-mails introducing myself and trying to set up a time for a

telephone interview. I knew I had found a friend when I asked him if

he knew the time difference between California and Cornwall and he

responded that he didn’t, but he could draw me a map detailing the

route between ancient Rome and Carthage. I then confessed that my

classical education had left me able to conjugate Latin verbs in the

pluperfect tense, but I had a hard time getting around Los Angeles.

Julian’s education in Rough Music leaves him equally erudite in arcane

facts but adrift when it comes to understanding his own heart.

Patrick and I scheduled our interview for 11 A.M. on September 11,

2002. And, of course, the world changed forever earlier that morning.

We postponed our interview and a few weeks later, Hero magazine

went out of business. I contacted Patrick to let him know and we kept

chatting–this time about the confusing state of the world and our

own sense of loss. When Ballantine Reader’s Circle contacted Patrick

about being interviewed for their trade edition of Rough Music, he

suggested me for the job. I’m so glad he did.

LD: What was the original topic you intended to explore in

Rough Music?

PG: I had originally planned to write about my parents’ marriage.

They’ve been together over fifty years and the dynamics of

their relationship and story fascinates me. So I thought I could

pay them a sort of homage in fiction. Naturally once I started

writing I realized I couldn’t possibly tell the unvarnished

truth as it would have been a gross crime against their privacy

and feelings. So instead of writing a family’s historical

biography, I aimed at telling its emotional one.

LD: Did the story surprise you as it evolved?

PG: I rarely keep to the story I set out with and in this case I

was deeply surprised. I found myself identifying more and

more closely with Julian/Will until it reached a point where

I was revealing very private things about myself even as I

was shielding my parents’ privacy with fictive devices. It’s a

truism that first novels are the most autobiographical ones.

There’s been a lot of me in all my novels but Rough Music is

by far the most personal.

LD: What inspired you to write two parallel stories?

PG: Most of my novels have fairly complex structures because I

mistrust narratives told from a single character’s viewpoint.

To get to the emotional truth of a situation, I need two

or three angles on it, which means two or three narrative

threads. The big inspiration here was my editor at Harper-Collins

in London. She’s a real toughie of the old school and

when I ran the initial ideas past her and asked, "Should I do

it this way or should I do it that way?" she snapped, "Do it

the hardest way, darling. That’s usually best." So instead of

telling first the past narrative then the present one, as I’d

done in The Facts of Life, I set out to interweave them.

LD: Did you ever feel as if you were writing two different novels

with two separate casts of characters?

PG: The beauty of interweaving the time frames was that it

hugely enriched the initial idea. What began as a story about

a marriage soon turned into a study of memory and our relationship

with our personal histories. I didn’t need to spell

out the fact that here was a group of people (Will especially)

who would never cope with the present so long as they deny

the past they’re dragging around–because the structure

was doing that for me. But to answer your question, no. I

wasn’t writing two novels, I was writing six. In order to ensure

that each character in a book has a narrative that hangs

together, I tend to write "their" chapters consecutively. This

causes terrible headaches when I come to weave the different

strands together.

LD: Your title comes from the old-fashioned practice of a

community making a ruckus near the homes of people

whom they found sexually offensive. Can you talk about the

title and how it relates to Will’s and Frances’s emotional

journeys?

PG: Rough Music is about transgressive sex and its consequences.

In both sections of the story a character commits

incestuous adultery and gets caught. Rough music was a

time-honored way in which a community expressed its disapproval

of sexual misconduct. In England there are recorded

instances of this in rural communities as recently as the 1960s.

More recently we have witnessed bloodcurdling scenes in

which communities mobilize against suspected pedophiles

exposed by the tabloids as living quietly in their midst. In

the novel I play around with the resonances of the title too,

so that there’s the soul music young Frances dances to on

the beach and the clattering of Roly’s sound sculptures as

well as the social clamor that erupts when the two adulterous

liaisons are exposed. I wanted, too, to show how that exposure

might set one character (Will) free to love more

openly, but for another (Frances) only emphasize the extent

to which she is socially trapped.

LD: Memory plays an important role in this story. How has

memory figured in your own life and in the writing of Rough

Music?

PG: The novel was full of things I thought I’d made up and when

my mother read them she’d say, "How did you remember

that? That’s exactly how it was!" She was a very keen

photographer. Every moment of her marriage and our childhoods

was photographed and stuck into a series of meticulously

kept albums. So I think I not only went to those albums

to research, but–by looking at them all during my childhood

and teens–swiftly reached a point where I couldn’t tell

my actual memories from the memories my mother had

recorded. It was amazing, too, how cathartic writing this

story became. When I wrote the chapter where Julian’s parents

leave him at the choir school without saying good-bye, I

felt this volcanic anger boil up in me because I remembered

how my mother had done that to me when she left me at my

choir school. So after all these years of never discussing it, I

had to ring her up and yell "How could you have been so

cruel?" And she got all teary and said she’d cried and cried

for days afterwards but had thought it was all for the best.

We both felt so much better after that. I didn’t realize until I

got so angry that I’d never really forgiven her for abandoning

my eight-year-old self to a bunch of schoolmasters.

LD: You relate the Greek myth of "Pandora’s Box" to the secret

lives of the characters in Rough Music. Can you comment on

that?

PG: As part of my research for getting inside Julian’s head, I

reread the books I was reading at his age, and among my favorites

was a well-thumbed book of Greek myths. I’ve always

found the myth of Pandora far more effective than the

story of Eve as an explanation of how so much sorrow and

sickness got into the world. Like the story of Eve, it begins

Rough Music with a woman being categorically forbidden to do something,

which of course she goes straight ahead and does.

What right-thinking woman wouldn’t? It stands to reason

that you should have whatever it is they least want you to

have, because that must be the thing they value most. But

unlike Eve’s story, "Pandora’s Box" has a touch of humanity

to it, because although her curiosity lets out all the bad

things from the box, she shuts the lid in time to keep hope.

Many of my novels have grim events in them–violent

deaths, suicides, madness–but I like to think that I make

these bearable for the reader by giving the characters reasons

to hope. In Rough Music there was no arguing with the

terrible fate that Alzheimer’s has in store for Will’s parents,

but I was able to end the novel with Will on the verge of

what might turn out to be real happiness.

LD: Like Julian, you grew up in the shadow of an English prison.

Aside from growing up in a governor’s house, have you taken

other facts from your own life and family to tell this story?

PG: Oh yes, and most of them will remain closely guarded secrets.

Julian is emotionally me, that much is true, but his life

in the prison is an amalgam of the things my older brothers

and sisters got up to. I did have an affair with a married

man. And in the middle of an unhappy time in my childhood,

a kind schoolteacher and his wife invited me to stay

with them in their house above a glorious beach in North

Cornwall so that we could all take part in a music festival.

This has far reaching consequences, not least my moving to

Cornwall when I grew up and writing a series of novels set

down there, including Rough Music. As for the music festival,

I’m now on the committee!

LD: Do you have personal experience with Alzheimer’s? You

write about Frances’s affliction so compassionately.

PG: My mother always tended to have friends much older than

she and, inevitably, I watched several of them become very

strange.

Also my grandmother, whom I adored, became horribly

confused and had to be put into a nursing home before she

died. But a lot of Frances’s experience of Alzheimer’s is

based upon my mother’s experience of having several

strokes in her life. She was in a car crash about thirty years

ago, which caused her such severe brain damage she lost the

ability to speak, write, walk, anything. She made an almost

full recovery, apart, tragically, from her ability to play the piano.

As a result, I’ve always been haunted by the way in

which our personalities, our public personalities at least, are

so rooted in our use of language. When Alzheimer’s destroys

that language, or when a stroke does, it’s as though the personality

is being torn apart like a cobweb.

LD: One of the themes you explore throughout Rough Music is

forgiveness. Each member of the Pagett family seriously betrays

another at some point during the story, but is subsequently

pardoned. Do you think the Pagett family is

unusual in their capacity for forgiveness?

PG: I hope not. I think the rise of a therapy culture may be creating

a climate in which we’re too ready to blame rather than to

forgive. I worry sometimes that we’re apt to confuse forgiveness

with forgetfulness. The potency of forgiveness comes

precisely from the fact that it must be done while being

goaded by an unhappy memory. Especially in the context of

relationships and marriage, I fear we’re coming to have crazily

high expectations of each other. I’m not saying unhappy wives

and miserable husbands should stay together at all costs, but I

do think a lot more could fashion something lasting, maybe

even, ultimately wonderful from their relationships if they

could stop expecting those relationships to be perfect.

LD: Will is a happy man, despite his loneliness. And Roly has

taught himself techniques to stay focused on the positive.

Do you believe that happiness can be learned? Do you

think of yourself as a happy person?

PG: One of my inspirations for Will and Roly was a documentary

I saw about an Oxford University clinic where it has been

proven that happiness consists largely of learnable techniques.

The idea is basically "Count Your Blessings." Some

of us are lucky in that we develop that habit of stressing the

positive from an early age; others go the other way. But the

bad habit can be unlearned, using much the simple techniques

Roly uses. Before beginning the novel, I was talking

with some friends about my childhood and they asked me

how someone with such a miserable start in life could be so

positive. This made me realize that I did think of my childhood

as basically happy, even though the actual facts of the

case don’t tally with my attitude. So I set out, in Will, to explore

someone facing up to just that challenge, someone

whose idea of themselves as basically happy could be shown

to be based largely on self-delusion.

LD: What are you writing now?

PG: I’m working on a novel with an even more complex structure,

effectively four novels in one. It’s set in the present in

the far west of Cornwall. It’s about two men, two women

and the child who holds them all together. In some ways it’s

pretty grim–much as Rough Music is–but it’s a hopeful

book too. Having given my childhood a good digging over, I

now seem to be rooting through the murkier corners of my

relationship history