Author Q&A

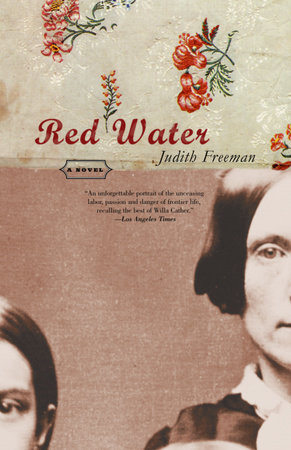

Can you tell us a little about your background and perhaps what inspired you to write about the early Mormon settlers, and in particular, the Mountain Meadows Massacre?

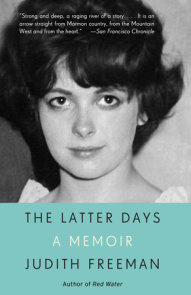

I was born in Ogden, Utah and raised in a large Mormon family of eight children. Mormonism permeated every part of my childhood—a culture as much as a religion. My parents were very devout believers. My father was also something of a liberal thinker, one of the few registered Democrats in a place full of Republicans, and he liked to talk politics and the state of the world over dinner. So even though I imbibed religion with my mother’s milk, I acquired a fondness for lively intellectual inquiry from my father. There were few books in the house, however, except religious books—faith-promoting stories about pioneers and , of course, The Book of Mormon,. My ancestors came from Cornwall, Mormon converts who settled parts of Arizona, Utah, and Idaho in the mid-l9th century in the first wave of Mormon colonists. .

Like many Mormon girls, I married young, at the age of seventeen, and by the time I was eighteen, I had a son. When I was twenty-one, I was divorced. But around this time I discovered literature and I began reading—Willa Cather, Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence—and I decided this is what I wanted to do: I wanted to write, to give expression to my own experience rooted in this world. By that time, I had left the church as well as the place where I grew up. I really didn’t publish my first book, a collection of stories, until many years later, after I’d raised my son. I’m a self-taught writer. I feel that I taught myself to write by reading novels I admired.

I never imagined myself writing a novel set in the l9th century until I came across a book about the Mountain Meadows Massacre, about six years ago, in a bookstore in Port Townsend, Washington. I had heard almost nothing about this massacre when I was growing up. It was a shadowy, never-spoken-about affair. The story grabbed me. I wanted to try to understand that kind of institutional violence and fanaticism—how could such good and decent men be persuaded to commit such butchery?

There was also this: My great-grandfather was a friend of John D. Lee’s. I kept coming across the names of my own relatives in the story. Another ancestor was Brigham Young’s Indian interpreter and played an interesting, albeit off-stage, role in the events leading up to the massacre. So the story had immediacy for me. It became irresistible to me.

John D. Lee was the actual man tried, found guilty, and executed for the massacre. Are Emma, Ann, and Rachel based on historical figures as well?

Yes, they were actual wives of Lee—three of his nineteen wives. I was able to locate the diaries and writings of these women, which proved very helpful. For instance Ann, who was only thirteen when Lee married her, wrote a memoir late in her life called “My Life with a Saintly Devil.” It’s a remarkable document, and even if only half of what she says is true, it sheds a very different light on early Mormonism.

Polygamy has been in the news recently with the trial of Tom Green, charged with and found guilty of having five wives. The public was fascinated by pictures of Mr. Green surrounded by his wives and twenty-five children, and with the courtroom tales of wives confessing their love and devotion to him. RED WATER gives us a look at polygamy from inside one Mormon family. What traditional notions of polygamy and Mormonism do you confirm and/or challenge in the novel? Through the course of writing RED WATER, did your views on polygamy change or evolve?

First of all, there was polygamy in my own family. My great-grandfather spent six months in the Yuma Territorial Prison for refusing to give up one of his wives. This was in the l890’s, after polygamy had been outlawed. When he was released, he simply went back to his two wives and led a good life, later becoming one of the first state legislators in Arizona. When I was growing up, a picture of him in his striped jail uniform always sat on display. There was no shame in having a jailbird for an ancestor. In fact, we felt a certain pride.

In writing RED WATER, I came to see polygamy in a somewhat different, less romantic, light. While researching the book, I realized that only a certain elite group of Mormons were allowed to take multiple wives. That the bestowing of wives—gaining permission from the authorities—was a kind of reward system for good service to the church. I also became more aware of the sexual predation involved. That’s a strong term, but how else to describe the fact that all these old geezers were allowed to marry such young girls who really weren’t old enough to have much say in the matter? Growing up we were taught that polygamy had been a holy institution, a Divine Principle, an edict from God for the betterment of man. Well, men are men, religious or not, and sex played a bigger part in this idea of “multiple wives” than I think people have admitted. I find the Mormon culture a highly sexual culture, lusty in spite of the veneer of primness. There’s a kind of precocious sexiness and I think this is a residue of the early polygamous culture.

You paraphrase the Book of Mormon quote, “It is better that one man should perish than a whole nation dwindle in unbelief,” in RED WATER to explain Brigham Young’s sacrificing of Lee. You also imply that the Mormon Church and Young condoned the massacre, hid the evidence and later to quiet the masses, arranged a guilty conviction that led to the execution of Lee. Does the Church today admit their involvement in this embarrassing historical incident.

I’m afraid the Church still insists on fudging on its part in the killings. The current leader has been quoted as saying it was simply the work of a bunch of “local fanatics.” At least he didn’t resort to saying what was claimed for a long time, which was, “The Indians did it.” It seems people still can’t tell the truth about this thing. Even the monuments—and there have been several erected at the site—-just say more or less, a bunch of people died here in an unfortunate massacre in 1857. Not one marker has ever said who did it. That’s for you to guess. Unfortunately most peoples’ first guess is, oh, Indians must have done it. The obfuscation on the part of the church, the state, all agencies that have had a hand in putting up those markers, really annoys me. But perhaps the site itself will demand justice: one recent marker, a rather large, ugly slab that listed the name of every man, woman and child killed without saying who killed them, was completely destroyed in mud slides and rains a few years after it was erected. You really feel this place is haunted by dead souls when you visit the meadow. I just hope the new marker falls down, too, until they get it right by telling the truth. Then maybe those ghosts can rest. The Indians, incidentally, might like that, too.

Rather than simply recreating the life and death of John D. Lee, you tell the story from the viewpoint of three of his wives. Each part of the book assumes a different structure—Emma’s monologue; the third voice for Ann’s story; the diary entries of Rachel. What is the significance of the various narrative styles and the order?

I wish I had a really good answer for these questions, but I don’t. I work on intuition. I never outline a book. I feel my way into the story, and it took me a long time and a lot of patience to feel my way into this one. This was the most difficult book I’ve ever written. It took five years to complete. Ann’s story came first, the story of the horse thief, but I didn’t quite trust it. Then I found Emma’s voice, and she became my primary guide and led me back to Ann, who now seemed to fit. Rachel came last, and I relied on her husband’s daily diaries for a certain tone and many details. It’s the harshest section, but I wanted to try and tell the truth about the incredible difficulty of a woman—now a widow—alone in that impossible landscape, and a diary, filled with the mundane as well as her spiritual obsession, seemed the best way to do it.

Regarding the Indians, Emma states, “Generally speaking, the women fared better than the men.” Why? Could you also be referring to John’s wives.

The quote comes from an actual settler’s diary, so I’m guessing what the writer meant. But since Native women didn’t engage in warfare, nor did they hunt—two dangerous activities—I presume they suffered fewer injuries. Also, women of all cultures seem better at administering medicine and nurturing each other, an important skill on the frontier.

As far as John D. Lee’s wives, they certainly suffered incredible hardships and psychological trauma—they had to share his shame and the shunning, and later a life of exile—but they were spared the actual experience of the massacre, which haunted every man who participated in it until the end of his life. Nor were they the ones required to face a firing squad. In this sense, they certainly fared better.

From England, Emma brings one book, An Encyclopedia of Greek Mythology, given to her at age twelve by her mother, and carries it as she journeys west and moves from settlement to settlement. Why did you choose this book?

I think it chose me. The idea came to me that these “stories of multiple gods and goddesses” would suggest an exact opposite to the Mormon belief in one, male, god, absolute in his power and authority.

Red, the color, permeates your novel and not just the physical landscape. What is the significance of red in the novel? And secondly, what is the significance of water, and in particular red water, in the title? Why the inserted epigram about red?

I am hesitant to try to decode my own metaphors and symbolism, but I will say this: one of the bloodiest tales in all of Western history lies at the heart of RED WATER. Obviously, the color red suggests this blood, the blood of the innocent victims, including all those children (over fifty children were killed in the massacre). Like the wine of the Catholic sacrament, meant to symbolize blood, this is the original red water. Red is also truly the color of the land in southern Utah, a kind of other-worldly landscape. And, as the C.K. Chesterton quote at the beginning of the book suggests, red is the strongest color in the spectrum—“the highest light” and “the place where the walls of this world of ours wear the thinnest and something beyond burns through.” The truth is that while writing this work I felt myself transported to another place, where something beyond did indeed burn through. The voices of three women came to me from another century, as if the walls dividing time, and my own sense of being a separate individual, had dissolved.

You’ve published four other books, Family Attractions, The Chinchilla Farm, Set for Life, and A Desert of Pure Feeling. Are these also novels? Are they also based in history?

Only insofar as memory is an act of history. No, these books are all set in my life time, meaning more or less the last half of the 20th c. They are all fiction—the first a collection of stories, the last three novels. If there’s history to be found in them, it’s my own.

What’s next for Judith Freeman?

I’m thinking of a book I call “The Story of Bob,” about the death of my brother. He was my oldest brother, who died at nineteen, from bone cancer, when I was only eight. He’d dropped out of high school and joined the navy. He looked a lot like James Dean—incredibly handsome. In the navy, he spent time on ships in the South Pacific during the early l950’s, when they were conducting nuclear tests. He married an older woman from Columbia on a shore leave, then found out he had cancer, and died just after their baby was born. Recently, I’ve begun to wonder, was he one of those sailors who witnessed the atomic tests in the South Pacific, and did this have anything to do with his getting cancer? I’d like to research this, and write a kind of non-fiction book about Bob. It could be a way of writing a memoir but I could fool myself into thinking it was about my brother and not me. And I really would like to find out what happened to him.