Author Q&A

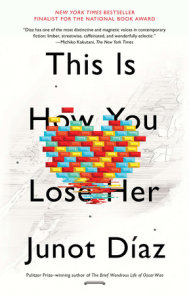

How has your life changed since the publication of Drown a decade ago? Was the sudden acclaim energizing or disorienting?

We’re talking eleven years (to be exact), so of course one’s life is bound to change plenty. But Drown acted like an accelerant, it put things into overdrive. To be honest, in real terms, the publication of my first book really didn’t produce much acclaim. I was known among the story-writing nerds and the MFA types and the New Yorker crowd (whoever they are) and in certain sectors of the Dominican community, but that was about it. Still, even that little bit of “fame” was a lot for an anonymous immigrant kid from central Jersey who’d worked his way through school. As for its real effects: I sure wasn’t ready for that kind of attention (by which I mean any kind), so after the book was published I found myself withdrawing deeper into my core of friends (most from childhood), into my students, into my work. I was (and am) super-self-conscious, but Drown made me even more so. Don’t know why. But my God: I’ve seen the world because of my writing, and met the most extraordinary people. Drown has given me a contemplative life and allowed me to support the causes I am most passionate about, and help other writers and shine light on a minute fraction of the New Jersey Dominican experience. It’s been a source of joy in spite of my discomforts, and that’s the way of most good things, I suppose.

Why do you think people responded so strongly to that story collection, and still remember and talk about it?

Man, even my publisher calls my first book a short-story collection! Okay, for the record: Since its inception, Drown was neither a novel nor a story collection, but something a little more hybrid, a little more creolized. Which was why we didn’t put “Stories” or “A Novel” on the cover. We wanted folks to decide what it was, as long as they didn’t foreclose that it could also be something else, ¿entiendes? Okay, enough about my categorical anxieties . . .

Regarding your question: I’ve been really fortunate. Drown is one of those little-known books that stays in print because a sector of folks just seems to like it. (Could I say anything more immodest? Just watch!) To an extent it’s been popular with teachers, with students, with lit heads, with readers, all kind of folks, really. Young writers like it because it’s structurally instructive and also because its emotional honesty seems like something worth aiming for, surpassing. In Drown, I wanted – in a fictional way – to bear witness to the experience of one family in the Dominican Diaspora, one American family, in every meaning of the word, and when you try superhard, as an artist, as a historian, as a storyteller, as a human being, to bear witness, when you throw your heart into that effort, people (if you’re in the right place at the right time) tend to respond. Okay, maybe it’s all luck. Still, I’m happy that Drown continues to move people. It makes all the years of silence and solitude worth it.

Why did you wait eleven years to publish a second book, which is also your first novel? Were you concerned about living up to the critical and popular success of Drown?

I wish I could have written four, five books in the span of those years. Just couldn’t do it. Didn’t help that the novel I was trying to write at the start of that period was about the destruction of New York City by a psychic terrorist (my very own Third World Akira) . . . a novel that 9/11 ended real fast. Had to rethink the whole thing, was too busy experiencing the transformations in-country to write about them in an interesting way. I still have parts of that novel on my desk, and it’s wild, watching Heroes, to see how common our apocalyptic nightmares are (New York City gets killed by a superhuman in that story too), and also how compelling. But it was more than just being sideswiped by history. Other stuff. Being scared, for sure. I can put the pressure on myself like nobody’s business. Years of depression didn’t help (if you’d grown up in my family you would have been depressed too). My own struggle against myself. Here’s another theory, which the writer David Mura told me: You have to become the person you need to be in order to write your book. I guess it just took me ten or so years to become that person.

What new emotional and literary challenges have you taken on with The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao?

This is a novel that was born after the death of my Black Akira novel. I’d gotten a Guggenheim (thank you, John Simon!) around 2000 and spent a year living in Mexico City. Trying to write, trying to clear my head, trying to improve my Spanish. I lived next door to my friend and the greatest writer alive, Francisco Goldman, and we had all these adventures, spent many a night getting into trouble in the big bad Distrito Federal. Anyway, one time after a night of partying I picked up a copy of The Importance of Being Earnest, and I said Oscar Wilde’s name in Dominican and it came out “Oscar Wao.” A quick joke, but the name stayed with me, and next thing you know, I had this vision of a poor, doomed ghetto nerd, the kind of ghetto nerd I would have been had I not been discovered by girls the first year out of high school. I remember dashing the first part out in a couple of weeks. I thought it was a story, nothing more. But Oscar wouldn’t stop hanging out in my head, and I realized that I wanted to write an entire novel about a Dominican kid who doesn’t get the girls, who can’t dance, who is the opposite of all the stereotypes that we inside the Dominican community have about “our men.” I wanted to write about this nerdy romantic kid who’s haunted by history and girls, who’s good only at fantasy and science fiction, and yet who (tragically, hilariously) belongs to a community and to a larger culture that ain’t too hot on men-of-color nerds or their interests.

But the real challenge was in trying to create a voice, a narrative, that would allow me to talk about Zardoz and the dictatorship of Trujillo and ’80s urban hip-hop and Broca and the Diaspora Dominicana and E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensmen and Latin Paterson and Unus the Untouchable simultaneously. Maybe for you that wouldn’t be nada, but for me it was a challenge and a half. I wanted a narrative that could be top-level hilarious and top-level heartbreaking. I wanted a narrative that could be hip about the present yet also render the past not as something dead or shackled inside sepia tones but as something dynamic, with all its confusions, excitements, disappointments, and energies intact.

And (finally) there was this very brainy interest I had in these weird (and in my opinion reductive) arguments in Latin American letters between the forces of Macondo and McOndo. The short version is that Force McOndo claims that the “New Latin America” cannot be usefully described by the traditional magic realist literatures of the Boom (Force Macondo). Only something as contemporary and MTV-ish as McOndo can do that. One movement seeking to displace another. And me, I’m thinking, like a Caribbean, why can’t we have ’em both simultaneously? So this book was an attempt to put Macondo and McOndo on the same page, in the same sentence, sort of to prove that you can’t write the American experience, our American experience, by banning one set of passports in the process of privileging another. When I’m in the DR or Colombia or Havana, I go to both salsa and dance clubs. I have one Cuban friend who’s into H. P. Lovecraft like crazy and another who’s convinced that the ancestors and the orishas speak to all of us. In the DR you could be watching the Red Sox on satellite one minute and then hear a ghost story the next. In my opinion, if you really want to get close to describing what’s happening in the New World, what’s happened, you’re going to need it all. Every narrative strand you can muster. Every genre and convention. A celestial mongoose? A heroin-addicted stripper-dating uncle? I’ll take ’em both.

What is this new book about?

It’s about the Dominican version of the cursed House of Atreus. And it’s about this young nerd, Oscar, who risks his whole life on the chance of finding love. It’s also about New Jersey and about Rutgers and about a crazy dictator and about cheating-dog men and how none of the hot women I grew up with wanted anything to do with dudes like Oscar. And it’s about the foundational women in Oscar’s life: his mother and his sister.

How autobiographical is this novel? More specifically, who is Oscar to you? And Yunior, your main narrator, whose identity is concealed until halfway through the book, who is he?

Well, I was hoping that this book was crazy enough that no one would ask me if it was autobiographical. I have (as yet) not encountered a celestial guardian mongoose, but I did grow up Dominican in New Jersey. That aside, I certainly wasn’t Oscar, and Oscar certainly isn’t me. But like Oscar I loved to read sci-fi and fantasy and horror and pulps growing up. My escape from my father and my neighborhood.

In Drown, you gave us a world seen mainly through the eyes of young, macho, intellectual Latino men, who hadn’t been heard from very much in literature. But in your novel, you get inside the heads of not only different types of men, but also some very strong women, from three generations. Women are in some sense the heart of the novel. In one chapter you write in the voice of Oscar’s sexy sister, and your take on the life of his mother is quite tender and compassionate. Did you make a conscious decision to write from a female point of view, or did it arise naturally? Do you see this as part of your development as a writer and a person?

I knew this novel would live or die on its female characters. If the women Oscar falls for ring false, then Oscar’s loves would ring false, and if that happened, well, I might as well have given up the whole damn thing. So I worked hard on the Insane Objects of Oscar’s Affections. . . . Anyway, there I was, thinking that I just had to describe Oscar’s loves – and then Oscar’s mother, Belicia, happened. I knew I wanted to say some words about her, just so we could understand Oscar better, but I didn’t think she would take over the way she did. And man, did she almost take over completely. I ended up dumping hundreds of pages of Beli’s story because it was devouring everything else. She is epic in ways that Oscar can only dream of being; she’s the last survivor from a destroyed family who lives in the wastes of Santo Domingo as a desperately impoverished orphan until she is rescued, Dickens style, by a distant aunt. Beli’s this young, yearning, beautiful girl living inside the shadow of this sinister dictatorship. As a result she is forced to become strong at a fundamental level, strong in the way only women tend to be. Beli as a character turned into a tribute to an entire generation of women I grew up with (my mother, her sisters, my friends) who had come to the United States and given their lives to build our community, to make people like me possible. Beli, in a way, was the key that opened all the other women in the book: her daughter, Lola; her adopted mother, La Inca; her real mother, Socorro. I found that I couldn’t write just about Beli, I had to circumscribe her entire female world. So here’s my confession: Beli and her story made me do it.

Writing across gender lines is hard. There are only a few writers who can do this well, and most of them are women. Toni Morrison writes some goddamn good men, and so do K. J. Bishop and Edwidge Danticat and Octavia Butler. I wanted to write about women as well as these sisters wrote about men; that was my goal, my dream. So of course I had my work cut out for me, and of course I’m going to agree with you that it’s part of a writer’s development to attempt to tell these cross-gender stories well.

Because of your subject matter and your cultural background, this novel will have obvious appeal for Latino and especially Dominican readers. Do you worry that it might be seen too narrowly, as appealing to those readers only? What are the broader themes here? What would you say particularly to non-Latino readers about why they should read this book?

How do you phrase this question for more “mainstream” writers? “Do you think your whiteness and your white subject matter will limit your appeal?” I’d love to hear the answers to that one! Call me crazy, but I happen to be one of those writers who think that the Dominican experience is a universal experience. What scares me is that the sci-fi and fantasy and fanboy content of this novel, not its dominicanidad, may narrow its appeal. People (I should put that word in quotes) visit (another quotable) the Dominican Republic because they want to experience certain kinds of packaged otherness, not because they want to hear some guy going on about the Dionysian architects in From Hell. But that’s how it is with all art: You construct an imaginary audience in your work and then you hope that its real-world analog will actually show up. Whether it occurs now or two hundred years from now is another question. I just happen to believe that folks of all cultures and colors, and grad school types and immigrants and lexics (people who love to read) and fanboys and fangirls and love-story addicts and lit heads and homeboys and homegirls and history buffs and activists and family-epic lovers and nerds can all sit in the same room together and blab usefully. In fact, I believe that all of the above were meant to sit in the same room and blab usefully to one another. I’m idealistic that way.

There are a lot of literary references in this story, from comic books and science fiction to Henry Miller and Ayn Rand. But the dominant one is J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. What role does it play here?

I’m not sure The Lord of the Rings is the only shadow text lurking inside the book. One could argue that the movie Virus and the anime/manga Akira are also important. But if I have to choose, I’d say it’s both The Lord of the Rings and the work of the comics titan Jack Kirby that whisper constantly through these pages. Tolkien certainly is a favorite of Oscar, the protagonist, and also of the narrator, Yunior. Like a lot of young readers I grew up with Tolkien, back when the only film was that Ralph Bakshi craziness. For better and worse, dude shaped a lot of contemporary fantasy conventions and fantasy audiences, and for me – for someone who grew up in the shadow of the Trujillato, the Dominican Republic’s once and future dictatorship – it was hard to think about that awful reign without comparing it a little to the Sauronic menace in The Lord of the Rings. It’s not that Trujillo was a Sauron; both Sauron and his master Morgoth were asexual and global in ways that Trujillo never was, but all three Dark Lords (Morgoth, Sauron, Trujillo) sought to achieve total tyrannies, the Lidless Eye everywhere, and there’s much in their projects that resonates.

Kirby’s work is equally vital to the book: his insane creativity, his cosmic-level mythologies, and iconography, which flipped my lid when I was growing up. I mean, consider his signature villain, Darkseid, whom I also tie to Trujillo: Darkseid and his Omega Beams and their ability to encapsulate a person – have you ever heard or seen anything like that? You have if you grew up in Santo Domingo. And then there was Kamandi. When Oscar dreams the end of the world, he dreams in Kamandi lines. And I’m sure it’s obvious to those who read the novel that I’m a huge fan of Kirby’s character The Watcher, who seemed to me the ultimate parigüayo, a perfect symbol for both Oscar and my narrative persona.

I’m sure you don’t know what the fuck I’m talking about. I’m sorry! But what matters is this: In my youth the only people who really seemed to be interested in exploring dictatorlike figures were the fantasy and science fiction writers, the comic-book artists. You didn’t see much about that aspect of the world in the mainstream culture, so as a kid who was the child of a dictatorship I had to find analogs in the genres, and since that was the language that explained to me the scope and consequences that kind of power has on people (on myself), that was the language I deployed to explore those very questions in my own book.

Which writers have influenced you the most? Which ones do you read for pleasure?

No surprise: I read a lot. I love and have been influenced by (I hope) the usual suspects: Los Bros Hernandez (I owe them almost everything), Samuel R. Delany, Toni Morrison, Edward Rivera, Octavia Butler, Leslie Marmon Silko, Sandra Cisneros, Richard Slotkin, Piri Thomas, Harlan Ellison, Maxine Hong Kingston, Anjana Appachana, Stephen King, Arundhati Roy, Denis Johnson, J. R. R. Tolkien, Tomás Rivera, Enid Blyton, Alan Moore, Salman Rushdie, early Oscar Hijuelos, Edwidge Danticat, Haruki Murakami. But lately I’ve been nuts over Sven Lindqvist (nothing beats “Exterminate All the Brutes”!), Adrian Tomine, Steph Swainston (The Year of Our War), Chris Abani (everything), Chuck Palahniuk (everything), the poet Gina Franco, Natsuo Kirino (I absolutely love her novel Out), the Monster mangas, Ian R. MacLeod (The Light Ages rocks!), Jorge Franco (Rosario Tijeras!), and so on.

The weight of Dominican history hangs heavily over this book, especially the dictatorship of Trujillo. Is this something that Dominican-Americans are still very much aware of?

History weighs heavy everywhere. It’s just that very few people care to feel it. And no, I don’t think the average Domo in the Diaspora knows much about the Trujillato or its legacies. And I don’t think any book is going to change that. But maybe one person will be inspired to poke around, and that’s not bad numbers when you think about it.

What’s your own personal relationship to the Dominican Republic? Do you still have close family members there? Do you visit often?

What can I tell you? My home country is really screwed up, politically, economically, socially, but I love the place. It feeds my humanity. I go about three times a year. Still have family and friends, a life of sorts, allá. If you see me on the plane or waiting for my luggage, say hi, you know.

You’re a tenured professor of creative writing at MIT now. Do you find a conflict between your teaching and your writing, or do they feed each other?

I love my students to death, but it’s a lot easier to write when you’re not teaching. These are smart kids, so you put a lot into it, and that always takes its toll. But teaching is an attempt to give back, you know, so it’s hard for me to think of being a writer without teaching.

Have you decided what your next book will be yet? What are you working on now?

I’m trying to write my “Psychic Terrorist Kills New York City” novel. Guess I’m stubborn as hell. Or just stupid.