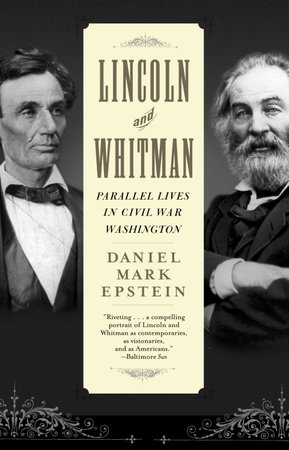

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Daniel Mark Epstein

Q. How long have you been working on this book?

A. Most of my life. I cannot remember when I had not read Walt Whitman’s poetry, and it has become as familiar to me over the years as Shakespeare or the Bible. In the 1980s I wrote a thumbnail biography of Lincoln, and during that time I read most of the major writings of Lincoln as well as the significant modern biographies. Putting the two greatest American figures of the 19th century together in one book occurred to me about three years ago; the writing itself took nearly two years.

Q. How did you get the idea?

A. I knew that Whitman had written a great deal about Lincoln. It was the discovery of Henry Rankin’s Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, with its eye-witness account of Lincoln reading aloud from Leaves of Grass in 1857 that made me realize there was a book to be written here. I knew that 1858 saw a dramatic development in Lincoln’s rhetoric. So I went directly to the speeches and compared them to Whitman’s poems. The influence was immediately apparent, and startling. Each man had influenced the other.

Q. You have a reputation for capturing a sense of place in your books: Chicago in the roaring 20s in Nat King Cole, pre-World War I Greenwich Village in your Millay biography. How were you able to bring to life Washington, D.C. during the Civil War?

A. I grew up in Washington. When I was a child in the the 1950s I walked the streets that Lincoln and Whitman walked, when many of the buildings looked much as they did to those heroes. So, more than in any of my books, the sense of place, weather, architecture and atmosphere came naturally. Then of course I owe a great deal to the 1860 maps of the city, contemporary travel guides, and the hundreds of Washington newspapers I read from cover to cover at the Library of Congress.

Q. Some Whitman scholars have called The Leaves of Grass an inherently political work, identifying the roots of democracy in Whitman’s sense of the common man, his egalitarianism and exuberant all-inclusiveness. To what extent do you believe this to be true?

A. With Whitman perhaps more than any other poet, the line between politics and “spiritual philosophy” is a very fine one. His first “free-verse” poem, called “Blood Money” written in 1850, was actually a protest against slavery in the territories. And Whitman even claimed that the erotic love poems in Calamus were political, and had to do with the love between persons being the glue that held together the democratic Union.

It is important to distinguish between the various editions and incarnations of Leaves of Grass in discussing their “political” content. The editions of 1855 and 1856, in defining the “self” and the ideal society, all-inclusive and egalitarian, are highly political. Later editions, as they include love poems (Calamus), war poems and elegies (Drum-taps) may be appreciated without concern for their politics.

Q. In what way were Lincoln and Whitman’s visions of America similar?

A. Both men believed in the principles embodied in Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence: that all men and women are created equal and are entitled to equal opportunities under the law. They both believed that the founding fathers stood against the expansion of slavery and that the peculiar institution would sink of its own weight and perish if it did not expand into the territories. And both believed that the American genius of the mid-nineteenth century, and the English language, were destined to lead the world–and the ideals of democracy–into the next millennium.

Q. Whitman is often heralded as New York’s poet, saluting every man and woman and child on the street, celebrating the bustle of Manahatta, Crossing the Brooklyn Ferry. But Whitman once told biographers “I was always between two loves- I wanted to be in New York; I had to be in Washington.” What kind of an impact did Washington have on Whitman? Why did he feel he had to be there?

A. Whitman had a journalist’s instinct to be at the heart of the action. Too old to serve in battle, the closest he could get to the war was the military hospitals–of which there was an extraordinary concentration in Washington–the White House, and the Halls of Congress. I believe that finally he felt he had to be in Washington because Lincoln was there; Whitman felt an extraordinary affinity with Lincoln.

Whitman’s experience in the military hospitals humbled him. The man who had glorified the “self” in Leaves of Grass discovered, in human suffering and sacrifice, values more important than the vaunting self.

Q. How was Lincoln’s oratory changed by Whitman’s poetry?

A. It is evident from the three public speeches Lincoln gave from June 1857-June 1858 (the last being the “House Divided” speech) that Lincoln learned from Whitman to raise his oratory from the level of rhetoric to dramatic poetry. Lincoln’s pre-Whitman speeches are marked by great powers of persuasion and storytelling; but they do not employ the figures of speech and poetic rhythms that make great literature and move audiences profoundly. The lyricism for which we now remember Lincoln begins in 1857, after his reading of Leaves of Grass. It was this lyricism, as employed in the “House Divided” speech, that got him elected President.

Q. To that end, the poet Kenneth Koch once said that one has to stand on a chair to read Whitman properly? Do you agree?

A. That was Kenneth being Kenneth, and very funny, but there is a wonderful truth in it. Whitman is BIG, a man with big ideas and big passions. We must become somehow larger ourselves in order to read him properly.

Q. For whom was there more of a divide between personal and intellectual life, Lincoln or Whitman?

A. For Whitman certainly. Whitman, for all his frankness in his poetry, was a closeted gay man of the 19th century; therefore there was an inexorable split between his personal and his intellectual life. Plied for an admission of his homosexuality by Edward Carpenter and Oscar Wilde who believed an honest statement from Whitman would be liberating to others, Whitman continually refused. While it might be said that Lincoln’s career was dramatically divided from his tragic personal life–due to his wife’s mental instability–his intellectual life, as revealed in his speeches and letters, seems to me to be a clear expression of his inner, personal life.

Q. Whitman’s verse, which was not even considered poetry by many, was both unconventional in its form and content highly controversial. How did Whitman challenge Lincoln’s sense of convention? And how did he inspire controversy?

A. I’m not sure that Whitman really did challenge Lincoln’s sense of convention; Lincoln was already about as unconventional as a nineteenth century lawyer could be. There were off-color words in Leaves of Grass that surprised Lincoln. Perhaps the sight of these words may have broadened the candidate’s sense of what could and could not be expressed in public. Whitman mostly inspired controversy by writing candidly about sex. And right after reading Leaves of Grass, Lincoln introduced some shocking references to sex between slavemasters and slaves in his speeches against Douglas.

Q. Both the President and the poet suffered great opposition in their careers. Who was ultimately more of an idealist, Lincoln or Whitman?

A. Whitman was by far the greatest idealist. He believed, like Shelley, that poets were the true legislators of humankind. He believed Lincoln was a great man when 90% of Americans thought the President a failure. He believed the Union would win the war when few others did. Lincoln shared Whitman’s political idealism, but the President had the calculating shrewdness of a practical politician and manager of men. Unlike Whitman, Lincoln was never blinded by his ideals.

Q. Whitman’s poetry celebrates himself and every human being; it is both highly individualistic and speaks powerfully to all Americans. How did the War for the Union affect Whitman’s sense of individualism? Did his sense of collective patriotism win out over his spirit of individualism?

A. In the short term, as I have mentioned, Whitman was chastened by his experience in Washington during the war. He came to submerge his personality in the larger experience of humanity. His elegy for Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” is the perfect expression of the poet’s new humility, as he gives the finest lines in the poem to the hermit thrush. But remember, only a poet of robust ego could write a poem as sweeping and heroic as that one. He had changed, but he was still Whitman. And twenty years after the war, as we see in his performance at Madison Square Theatre in New York, he was as vain as ever.

Q. Has your own sensibility as a poet informed your reading of Whitman?

A. Of course there are a number of things I understand about Whitman’s art that only a practicing poet could know. These are mostly technical matters, such as the concealed quatrain form in “O Captain, My Captain!” And then I can often tell when his attention wanders, or when he is allegorizing an experience from his life. But on the whole I would say that Whitman has informed my sensibility far more than my sensibility has informed my reading of Whitman.

Q. Which of the two heroes is the greater, in your estimation?

A. Oh, you put me in an impossible position! I think that my book demonstrates that both men were indispensable. We could not have had one without the other; our world would not be as good as it is if we had not been so fortunate as to have both.