Author Q&A

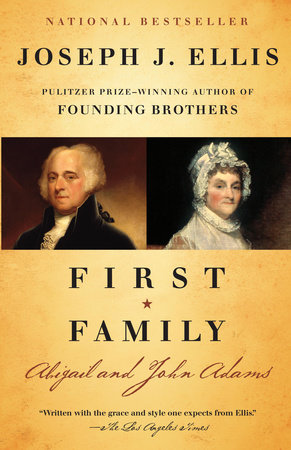

Q: You wrote about John Adams many years ago in Passionate Sage and, of course, he plays a role in Founding Brothers and American Creation as well as in your biographies of Washington and Jefferson. When and why did you decide to turn your attention specifically to John and Abigail?

A: As you say, my scholarly relationship with John Adams is longstanding. And if you hang around the Adams Papers long enough, you eventually realize that the “Family Correspondence” is the crown jewel. In earlier books I kept coming back to it for bits and pieces of evidence, and eventually decided that it was a story in itself that wanted me to tell it.

Q: How do you go about writing a biography of a couple, and their marriage, differently than you do writing a single subject biography?

A: Biographers of both John and Abigail invariably write about the other partner, but the partnership itself is a different kind of animal. I recall being impressed by a book by Phyllis Rose entitled Parallel Lives about five Victorian marriages. Perhaps that book gave me an idea that had been floating about in my subconscious for the last twenty years or so. Writing about them as a team also forces you to link the large political events they were living through with very personal issues like child-rearing, aging together, and health. In my judgment, that’s how most of us actually experience history. I very much wanted to capture that fusion of the public and the personal.

Q: How did they meet and was it love at first sight?

A: They met in the parlor of Abigail’s father, when John accompanied his best friend, who was courting Abigail’s sister. Abigail left no record of her first impression, but John did. He thought she was a boring, uninteresting, opinion-less young woman, not worth a second thought. It was definitely not love at first sight.

Q: You call the roughly 1200 letters between John and Abigail a “treasure trove of unexpected intimacy and candor, more revealing than any correspondence between a prominent American husband and wife in American history,” and, “the most comprehensive and intimate portrait of a prominent family living through America’s founding.” How is it that so many of their letters have survived?

A: Well, early on, by 1776, John and Abigail both developed a keen sense of the historical significance of their times and decided to preserve their letters for posterity and in John’s case to make copies whenever possible. In that sense, they were writing to us as well as to each other. Moreover, they were apart for such long stretches that they wrote more letters than most prominent couples of the era, or any era. So we know more about their most intimate thoughts, ironically, because of the distance between them. Thank the gods there were no cell phones back then.

Q: While, as you write, “from a historians point of view the geographic distance between them proved a godsend,” from a marital point of view it was an incredible hardship. It’s hard in this day and age to even imagine the kinds of absences they endured. How did it affect them?

A: Lacking emails or cell phones, space and time were experienced differently. Our presumption of instant communication makes it difficult for us to comprehend their world, where distance was non-negotiable. As I mentioned earlier, distance made letters necessary, a godsend for the historian. But it also generated a psychological and emotional space that required Abigail to become more independent than she might have otherwise, and John to become a second-hand parent and husband for long stretches. They had to imagine what the other was thinking or feeling more than most modern couples.

Q: Abigail and John launched their marriage at the same time the British ministry launched its legislative initiative to impose parliamentary authority over the colonies. You say this coincidence is worth contemplating. How so?

A: It meant that John was ready to play a prominent role in the run-up to the American Revolution because his marriage to Abigail gave him what he called “ballast.” And it meant that the cause of independence and the Abigail-John partnership would be forever linked throughout their lives.

Q: You write that both John and Abigail defied rigid gender categories. In what ways?

A: Each of them occupied the traditional roles, to be sure, John as the breadwinner and public figure, Abigail as the wife and mother. But both defied the gender boundaries as well. They shared parenting responsibilities and they consulted routinely about political issues. Instead of occupying separate spheres, they kept overlapping and, if you will, completing each other.

Q: You mention a letter Abigail wrote in the spring of 1776 as “her most famous.” What was in that letter?

A: This was the famous “Remember the Ladies” letter of March 31, 1776 in which Abigail somewhat mischievously noted that the arguments John was hurling against Parliament’s authority over the colonies had obvious implications for the authority of husbands over wives in a patriarchal society. John tried to turn the exchange into merely playful banter, but Abigail’s responses show that she was quite serious.

Q: How influential was Abigail in shaping John’s views and what were the issues on which they most agreed? And disagreed?

A: Well, you have to read the book to know the full answer, but they were in complete agreement on the question of American independence. They disagreed in the 1780s about John’s relative responsibilities as a father and husband versus as a statesman. And during his presidency, Abigail was a more ultra-Federalist who harbored no reservations about the passage of the Alien and Sedition Act. I think that was the one political occasion when she failed him.

Q: Much has been written about John’s relationship with Thomas Jefferson but you really shine a light on Abigail’s remarkable friendship with Jefferson. Can you tell us a little about their relationship?

A: Well, just to tease you a bit, Jefferson carried these clearly delineated gender categories in his head. And Abigail violated them by moving gracefully from conversations about silk gloves or silverware to observations about interest rates at the Bank of Amsterdam or recent speeches in Parliament. She was the first woman he came to know well that combined the traditional virtues of a wife and mother with the sharp mind and tongue of a fully empowered accomplice in her husband’s career. Jefferson had never before known a woman who could do that.

Q: You write at length about John and Abigail experiencing “the emergence of a highly partisan brand of party politics,” and, “the arrival of a political culture almost designed to torment him until his dying days.” John assumed the office of President in a most turbulent and nasty atmosphere. Do you think he and Abigail were prepared for this?

A: They thought they were, because they had witnessed the savage attacks on George Washington during his second term. But they had no way of knowing how much more passionately partisan it would get during John’s presidency, and both of them viewed the arrival of party politics as incompatible with their conception of virtuous political leadership. They saw themselves as the last members of a lost generation.

Abigail harbored a more moralistic, at times almost operatic view of politics than John. It was always the forces of light against the forces of darkness. She viewed the political factions of the 1790s through those categories, and came to regard all the Republican critics of her husband as traitors deserving jail time. While John lived to express regret about signing the Alien and Sedition Acts, Abigail never did.

Q: Of their retirement years you write, “The image of Abigail and John living out their last chapter together in secluded serenity was a complete distortion. Their retirement home was also a hotel, an orphanage, a child-care center, and a hospital.” Can you talk a little about their final years together?

A: The Quincy household during the retirement years was a boisterous and often chaotic place, and instead of some sentimental novel about domestic bliss, we should think of Eugene O’Neill’s dramatic depiction of a dysfunctional family. Abigail and John tried to make themselves into the calm center of an always raging domestic storm, populated by alcoholics, juvenile delinquents, hypochondriacs, and wounded creatures.

Q: For a couple passionately focused on legacy, the fate of the Adams children is not a happy story—one that involves unfortunate marriages, alcoholism, and suicide. Tell us a little about the Adams children and their fates.

A: Nabby, the eldest and only girl, married badly and lived an unhappy life that ended up in bankruptcy and premature death in her father’s arms from breast cancer. Charles became a hopeless alcoholic and drug addict who died at thirty. John refused to forgive him or even recognize him as his son at the end. Tommy failed as a lawyer and eventually moved back to Quincy for a lifetime of booze and prevailing incompetence. John Quincy, of course, enjoyed remarkable success as the preeminent statesman of his era, the poster-child of the second Adams generation, but he was a deeply conflicted man as well, who regarded his personal life as an abject failure.

Q: It certainly seems with the Obamas in the White House, the focus on and fondness for the first marriage, and first family, is as at a peak. Does their partnership in any way remind you of John and Abigail’s?

A: Eleanor Roosevelt and Hillary Clinton changed the longstanding pattern of First Ladies as social ornaments who played no substantive role in shaping policy. Michelle Obama, like Hillary, had a professional career as a lawyer, and currently leads the national campaign to combat obesity. But she also is committed to playing the conventional role as wife and mother who remains in the background. Abigail was the first First Lady who gracefully straddled those two roles. In that sense, Michelle Obama is following in Abigail’s footsteps perhaps more than any other First Lady.

Q: At the opening of First Family you write, “Abigail and John have much to teach us, both about the reasons for that improbable success called the American Revolution, and the equally starting capacity for a man and woman—husband and wife—to sustain their love over a lifetime filled with daunting challenges. One of the reasons for writing this book was to figure out how they did it.” So, how did they do it?

A: They were intuitively and instinctively aligned from the start, compatible emotionally and intellectually, learned how to grow together rather than grow apart, developed incredible powers of resilience and recuperation in the face of personal pain and tragedy, and enjoyed the luxury of living out their time together within the protective canopy of unconditional love, which was always just there.