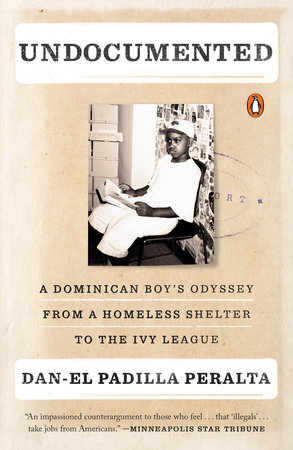

Author Q&A

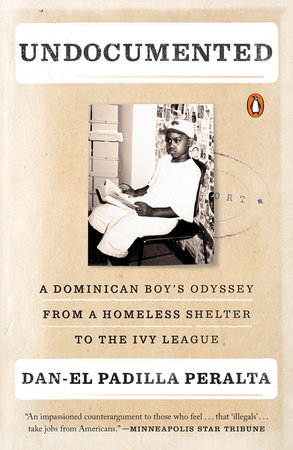

The memoir’s subtitle refers to your “odyssey,” bringing to mind Homer’s epic poem and its hero Odysseus. Why did you choose this word to describe your experience?

I chose to include odyssey in the subtitle to acknowledge my personal debt to Homer’s epic poem, the very first literary text from Greco-Roman antiquity that I read from cover to cover; on that initial eleven-year-old reading, I was gripped by Telemachus’s efforts to re/discover his father and inspired to reflect on my own upbringing without a father. Even to this day I find myself getting emotional when rereading certain passages: the encounter between the disguised Odysseus and his dog Argos in Book 17, one of the most exquisite—because emotionally devastating—recognition scenes in all of ancient literature, is a much-revisited tearjerker. The desire to evoke Homer’s poem is also tied to Undocumented’s autobiographical arc: at its core, my book is about how I came to value an education in the Greek and Roman classics and to develop a vision of myself as a professional classicist; and this journey to classicism required me to travel in many different worlds, some populated with Cyclopes and Laestrygonians too. . . . The presence of odyssey in the subtitle conveniently foregrounds some of the tensions in my story and its distillation for a public audience. Am I implying with the word odyssey that my homecoming was to the Ivy League? And what of the progression—let’s set aside the Homerizing for a moment—from homeless shelter to Ivy League: (how) does it validate an existing exceptionalist discourse (skillfully anatomized by James Baldwin in one of my all-time favorite essays, “Fifth Avenue, Uptown”) more concerned with the tropes and markers of individual success than with the institutional and structural realities that prevent many others from fully realizing their potential? In the hope of winking ironically at some of these questions, the placement of odyssey in the subtitle is intended to point ahead to the memoir’s mock-epic and counter-epic moments (the latter brought to the fore in the Epilogue’s closing words, a quotation from the close of Vergil’s Georgics).

Undocumented provides a very intimate view of your family’s struggles, including poverty, marital problems, and health issues, among others. Can you share any updates on how your family is today?

The family is flourishing! Mom married Carlos, and both are now U.S. citizens (and always eager to exercise the civic franchise). My dad is transitioning to a quiet old age in the outskirts of Santo Domingo. Yando graduated from Bowdoin with a BA in classics and worked for several years as a legal advocate for the Urban Justice Center in New York City before deciding to scratch the law school itch; he just completed his 2L year at Fordham Law and has been happily booed up for the past few years with the spectacular Dorothy, Barnard alumna and all-around superstar. Missy and I celebrated very festive nuptials in March 2015, with our friend Dave (companion in my Rome travels) and Missy’s brother Joe co-officiating. Alas, our nuptial bliss has coincided with a disgraceful turn of events for the New York Yankees. . . . We are currently waiting on USCIS to rule on my green card application—stuck in the bureaucratic machinery for over a year now.

You discuss how your brother felt he was compared to you throughout his childhood. What is his reaction to Undocumented and his portrayal in it?

I didn’t share any of the drafts with him (or any of my family members with the exception of Missy): he read it for the first time when I presented him with a hardcover copy. The next time I saw him, he wryly remarked that it was right for folks to know that at times he’d been an ass. But he’s been proud of the book—which occupies a place on his and his girlfriend’s bookshelf next to another 2015 Penguin release, Aziz Ansari and Eric Klinenberg’s Modern Romance—and a tremendous cheerleader for its author. He has floated the possibility of one day writing his version of events (joining Missy, who is threatening to write a memoir that will expose me for the chaotically disorganized and irregularly-committed-to-bodily-hygiene bundle of joy that I am . . .).

Immigration reform is an issue that elicits very strong opinions, especially during the current election cycle. Considering that the United States was founded by immigrants, where do you think today’s anti-immigrant sentiment comes from? Are there historical precedents to this?

There’s a deep history to contemporary anti-immigrant discourses that needs to be publicly acknowledged and reckoned with. Quite a few of those actively championing exclusionary and/or deportation-oriented policies are descended from immigrants whose presence in the United States was vilified for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Despite the insistence of some that studying this history is pointless—I recently sat on a panel in which a member of Congress dismissed the historical contextualization of modern immigration policy as irrelevant to understanding “reality” (#LOL)—anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies have been as integral to shaping our twenty-first-century cultural and political dispensation as has institutional racism. (It has not escaped my notice that those who are dismissive of the need to engage the latter with nuance and sensitivity tend to be similarly dismissive of the former as well.) American nativism reaches back to the 1800s and is the subject of multiple excellent historical and sociological works: two favorites are Mae Ngai’s Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (2004; superb on how the categories of “legal” vs. “illegal” immigration are erected on racializing—and at times explicitly racist—foundations) and David Scott Fitzgerald and David Cook-Martín’s Culling the Masses: The Democratic Origins of Racist Immigration Policy in the Americas (2014; the title says everything). Lately I’ve been interested in mapping an even deeper history of anti-immigrant sentiment by going back to the Greco-Roman world: the preliminary result of my explorations is “Barbarians inside the Gate,” a two-part series originally penned for the public-facing classics journal Eidolon and subsequently picked up by Newsweek in November 2015.

For those readers who might not be familiar with it, what is the DREAM Act and where does it stand today?

The DREAM Act was a bill, first introduced in 2001 by Senators Dick Durbin and Orrin Hatch, that would have provided a path to legalization and eventual permanent residency for select groups of young undocumented immigrants. Versions of the proposal were reintroduced in standalone amendment form or in conjunction with comprehensive immigration reform bills on both the House and Senate floors throughout the Bush years and in the first term of Obama’s presidency. The closest the proposal came to passage was in 2010, when the DREAM Act was passed in the House but fell five votes short of going up to the Senate floor for a full vote. Bowing finally to the realities of partisan obstruction and to the criticism of immigration activists, the Obama White House announced in the summer of 2012 the implementation of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals)—a program under which young undocumented immigrants who met certain criteria could apply for exemption from deportation and a renewable two-year work permit. Efforts to expand this program (DACA+ and DAPA, the latter for undocumented parents) have been stymied by the courts; US v. Texas, the case recently heard by the Supreme Court, is likely to result in a 4-4 split that will leave an injunction against the DACA expansions in place.

You wrote, “More now than ever, I believed with every ounce of my being that structures, contexts, and luck reigned supreme” (p. 280). Could you explain that idea in more detail?

It’s proven all too tempting for some folks (even those close to me) to read my life as a realization of the American Dream. Notwithstanding some of the marketing language employed for Undocumented, I have an adversarial relationship to any notion of the American Dream that does not pause to interrogate its underlying premises. I find it unsatisfying on both an intellectual and ethical level to use my life simply to rehash the platitudinous flim-flam that anything is possible if you just work hard and hope for the best. For starters, luck is huge—but even luck’s room to operate is hedged by the operation of racial and socioeconomic structures (segregated schools and communities, the carceral state and its immigration enforcement extension, accelerating wealth and income inequality, etc.) that conspire to marginalize and exploit the black and brown while the mythologizing pieties of the bootstrap are chanted in the background. Often wired into profiles of the “successful” immigrant life, these pieties have the effect of implicitly validating existing social and institutional structures; one of my motivations in writing Undocumented was to emphasize how perverse and deeply in need of immediate and far-ranging reform these structures are. I’m always thinking of my favorite passage in the aforementioned James Baldwin essay (see first answer above): “The people . . . who believe that this democratic anguish has some consoling value are always pointing out that So-and-So, white, and So-and-So, black, rose from the slums into the big time. The existence—the public existence—of, say, Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis, Jr., proves to them that America is still the land of opportunity and that inequalities vanish before the determined will. It proves nothing of the sort. The determined will is rare . . . and the inequalities suffered by the many are in no way justified by the rise of the few. A few have always risen—in every country, every era, and in the teeth of regimes which can by no stretch of the imagination be thought of as free.” Animating Undocumented is the hope that, far from serving as uncritical affirmation of the “Dream,” one person’s life can jumpstart criticism of the exploitative inequalities that grind down so many families and communities—so many black and brown families and communities.

In what ways, if any, are you still engaged with immigration advocacy?

I spend a lot of time talking about the fierce urgency of immigration reform: to schools, to community organizations, to institutions, to anyone and everyone who will listen. I have also spoken on behalf of politicians and political platforms that I believe are best equipped to effect substantive immigration reform (and by “substantive,” I mean reform that would provide a path to legalization and citizenship for the undocumented and wind down the preposterously expensive and unproductive obsession with militarizing the border).

What do you think your life would have been like had you stayed in the Dominican Republic? Do you plan on visiting?

I have an agonizingly hard time with counterfactuals. I think I would have found my way to the humanities somehow, both because my parents are such ravenous readers and because they were in a position—thanks to their middle-class employment in Santo Domingo—to send me to good schools where books and book-learning are treasured. (The emergence of a virulently anti-intellectual discourse in Santo Domingo might have impeded that humanistic self-realization—but then again, as Richard Hofstadter pointed out several decades ago, anti-intellectualism is a fixture of American life too.) I’ve wanted to visit the Dominican Republic for years but have been kept in the United States by the precariousness of my status. If/when my green card arrives, I will be making regular trips to Santo Domingo: partly to visit family, partly to pursue a project on the reception of Greco-Roman antiquity in the Dominican Republic that is keeping me very busy these days, and partly to continue agitating against the Dominican government’s treatment of Dominicans of Haitian descent (the subject of a July 2015 piece I wrote for The Guardian).

In light of all that you have been through, if you could say something to your childhood self, what would it be?

Aeneas’s counsel to his men in Book 1 of Vergil’s Aeneid: not the famous line forsan et haec olim meminisse iuuabit (“Perhaps one day it’ll be pleasing to remember even these things”—my high school Latin and Greek teacher’s encouragement to me when I was feeling down), but durate et uosmet rebus seruate secundis (“Bear up, and preserve yourselves for better things”).

Of all your many accomplishments, of which are you most proud?

Undoubtedly because of some masochistic reflex, I can’t work on one long project without nursing along another to provide justification for my procrastination (now get ready for the #humblebrag): as a Princeton senior I completed two 100-page theses, one in classics and the other in the Woodrow Wilson School; many moons later, and in keeping with the principle that all good things come in pairs, I submitted the final draft of Undocumented and defended and filed my Stanford dissertation in the same academic year. In a lighter vein: as a Princeton senior I participated in the first episode of the short-lived trivia campus show “Sixth Quintile”—and won on a final question about Gabriel García Márquez, if memory serves right.

I am not so much “proud” as I am relieved by the fact that after seven years Missy still puts up with my hot mess.

Classical literature and rhetoric fascinated you from an exceptionally young age. What is it about this writing that held—and continues to hold—such appeal? If you could recommend one ancient work to your readers, which would it be and why?

At the time of my earliest exposure to them, Greek and Latin literatures and cultures allowed me to indulge my imagination and fly away into a world some 2,000-plus years in the past. In the years since, I’ve come to see the study of Greco-Roman antiquity as a necessary and indispensable tool for responsible civic engagement. I don’t endorse ascriptions of transcendent value to Greco-Roman antiquity, preferring instead to see what value resides in classical alterity as negotiated through many centuries of contestation, disagreement, policing, and effacement; besides, I’m a rank hedonist, so in the end classical literature and rhetoric keep me interested because they give me great pleasure. But I see this pleasure as an occasion for the exercise of social responsibility and for the testing and recalibration of the field that I’ve come to love. If classical texts are indeed capable of accommodating a multitude of voices (and I’m one of those who believe that they do), then that capaciousness is best brought out by confrontation with the social and ethical demands of the here and now.

I always find singling out any one ancient text for recommendation hard. I’ve already sung Homer’s praises. Plenty of people still read the Odyssey, but not as many read the Iliad; so go read about the wrath of Achilles! Or spend some time in the company of that ethnographic genius Herodotus. On the Latin side, the prospect of a pumpkin-complexioned president has forced me to console myself with the satirical genius of Seneca’s Apocolocyntosis and Petronius’s Satyricon.