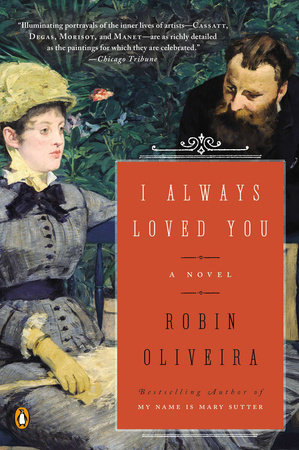

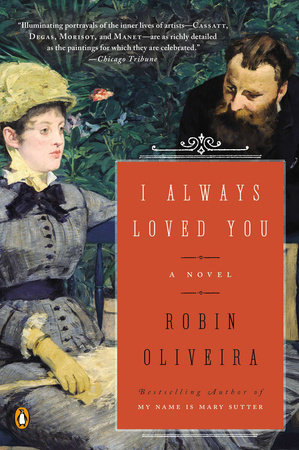

I Always Loved You Reader’s Guide

By Robin Oliveira

INTRODUCTION

“Mary thought that the art of love might just be blindness: the willingness not to see the truth of anything, to blur life’s sharp edges and drift on an impression of one’s own making, to act as if the life you lived was the life you wanted” (p. 196).

Paris, 1877. Mary Cassatt is at a crossroads. An American expatriate, Cassatt has spent the last several years in Europe, studying painting and working to establish herself as an artist. When none of her pieces are accepted into the annual École des Beaux Arts Salon, she is crushed and contemplates returning to America. But soon after, Cassatt meets her idol, Edgar Degas, a forceful and charismatic man, who overturns all her plans.

A few days before they are introduced, Degas notices a lone woman at the Salon. “The mystery woman was not beautiful . . . but her strict self-possession appealed for its singularity alone” (p. 25). He attempts to speak to her, only to lose her in the crowd. So when a friend presses Degas to meet an ardent admirer, the usually unflappable artist is stunned when Cassatt turns out to be the very woman he had pursued.

Although he had never met her in person, Degas had been struck by Cassatt’s work. He invites her to abandon the Academy and exhibit the following year with a nascent group of renegades who call themselves the Impressionists. “You will no longer have to subject yourself to the parsimonious Salon jury; you will paint what you wish to paint” (p. 43).

Instead of giving up art, Cassatt finds herself sipping champagne with members of Degas’s coterie, including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Édouard Manet, and Auguste Renoir. Cassatt longs to throw herself into new paintings and live up to Degas’s faith in her talents, but complications unexpectedly arise.

Cassatt’s father, mother, and invalid sister, Lydia, announce that they are leaving Philadelphia and will soon join her to live in Paris. The news brings Cassatt both joy and anxiety. She dearly loves her family-especially sweet-tempered Lydia-but she is expected to find and furnish accommodations that will satisfy both the family’s budget and her father’s capricious tastes.

Two women buoy Cassatt during this difficult time: Abigail Alcott, a friend and the sister of Louisa May Alcott, and Berthe Morisot, the only other female Impressionist and Manet’s sister-in-law and former mistress. Morisot tutors Cassatt on how to navigate the fractious Impressionists and, in particular, cautions her against succumbing to Degas’s charm. “You haven’t known him long enough to know that his regard can easily be withdrawn” (p. 93).

Initially, Cassatt is reluctant to think ill of Degas-and all Paris knows that Morisot herself is still in love with her husband’s brother. Why should Cassatt listen? Soon enough, however, she discovers the truth behind Morisot’s cryptic warning. Nothing-and no one-is more important to Degas than his art.

Painstakingly researched and dazzlingly rendered, I Always Loved You is a bravura performance by the New York Times bestselling author of My Name Is Mary Sutter. Through the dual prism of Cassatt and Degas’s unconventional romance and Morisot and Manet’s tortured affair, Robin Oliveira awakens a bygone Paris animated by the indelible personalities and passions of the men and women who changed art forever.

The New York Times bestselling author of My Name Is Mary Sutter, Robin Oliveira holds a BA in Russian and an MFA in Writing. She lives in Seattle, Washington.

Your previous novel, the New York Times bestseller My Name Is Mary Sutter, was also set in the nineteenth century. What is it about this period that captures your imagination?

The nineteenth century, in human terms, is fairly recent, and in historical terms is well documented in both the details of everyday life and historical events, rendering research relatively easy. I’m very interested in mixing fact and fiction, in setting my fictional characters in a realistic, historically accurate landscape. Nineteenth-century guidebooks, newspapers, photographs, diaries, street maps, etc., are all readily available; earlier centuries’ are less accessible. My characters adhere to real train and boat schedules, museum hours, and eat at contemporary restaurants. There is something grounding for me in having my characters operate in the same circumstances as those who lived in the nineteenth century. And I suppose I have a romantic notion of life then, which is probably less based in reality than I’d like to think.

What inspired you to intertwine Cassatt’s story with that of Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot?

In the structure of a novel, a subplot expands the main plot by contrasting and mirroring the story arc of the main characters. That is to say, the subplot comments on, reinforces, and delineates the main story by illustrating a different approach to the same conflict. In I Always Loved You, one of the conflicts is impossible love between soul mates. Once you undertake a study of the lives of the Impressionists, the pairing of Cassatt/Degas and Morisot/Manet is quite obvious. I am but one of many students of Impressionism who have recognized the parallel dynamics between the two couples. From a writer’s point of view, I was thrilled to discover the connection, because it served my literary needs very well: their differing circumstances and approaches to their similar predicament presented the perfect plot and subplot.

As a writer, it must have been fun to write the scene in which Degas and Zola debate the superiority of their respective art. Zola says, “Here is the difference between writers and painters. You are handicapped by your medium, paint, whereas a writer is a savant of sorts, using our more facile medium of words to inquire about and observe any subject. . . . Words reign” (p. 77). Do you agree with the argument he expresses?

I believe that paint is as facile and powerful a medium as words. The Impressionists revealed their own politics and views on contemporary society just as Zola’s essays and novels did; their themes mirrored one another. Zola’s realist novels L’Assommoir and Nana commented on modern life in the same way the Impressionists’ paintings did. No one can look at Degas’s In a Café and not understand his politics, nor can one look at any of Pissarro’s peasants-at-work paintings and not recognize his socialist leanings. Painters and writers alike were commenting on modern life with equal force.

The Impressionists both reviled and revered Zola. A compatriot of change, he was one of the first to champion their exhibitions, but he was often severely critical and arrogant in his critique; he also cruelly portrayed his childhood friend Cézanne in the novel L’Ouvre. I gave Zola those words in I Always Loved You to show that this conflict became an essential element of their interactions.

After Mary Cassatt’s first exhibition with the Impressionists, she is crushed by an abundance of negative reviews, including one that said, “The work of Madame Mary Cassatt betrays a preoccupation with attracting attention, rather than an attempt to paint well” (p. 200). Are they based on the original reviews or are they verbatim excerpts?

All the reviews are verbatim excerpts, with the caveat that I was their translator and, since I am not a native French speaker, may have made some errors. Wherever possible, I include the actual documents that pertain to whichever piece of historical fiction I’m writing. For instance, in My Name is Mary Sutter, I hunted down the original Sanitary Commission report on the Union Hotel Hospital, which took some doing. In the case of Mary Cassatt’s reviews, there was such a plethora of available authentic contemporary reviews that I deemed invention irresponsible. And the critics were so creatively insulting! I don’t think I would have been as original. And I loved that some of the critics also got her name and marital status wrong. That irked Cassatt and certainly would have irked me. Furthermore, the critics differed so greatly from one another in their opinion of her work; it was a pleasure to reveal Cassatt’s varied critical reception. I couldn’t have altered the reviews in any way that would have improved on the originals.

Lydia Cassatt suffered from a painful and lingering illness that goes unnamed in the novel. Does history record what it was?

It is believed that Lydia Cassatt died of what was then called Bright’s Disease. This disease title encompassed several conditions of inflammation of the kidneys, but the specific illness that afflicted Lydia cannot now be accurately identified from this distance in time. Nephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, or hypertensive nephrosclerosis are all possibilities. Modern treatment offers a variety of medications and antibiotic and, in the worst cases, dialysis, but these treatments were unavailable then. Lydia’s symptoms progressed and led to renal failure and premature death.

Degas’s losing battle with macular degeneration is one of the most tragic aspects of the novel. How many years did he live after he was no longer able to paint?

It is difficult to know exactly when Degas gave up painting, but the decline is generally believed to have been complete by 1909. Prior to that, he had begun to work only on very large canvases and smaller wax sculptures (Edgar Degas, Rizzoli). He died in 1917.

Is there any documented proof that Cassatt and Degas had-however briefly-a love affair?

The only documented proof would have been a letter or, failing that, a diary entry that we could authenticate. Since Cassatt burned all their letters before her death, there is no way of knowing for certain what went on between them on any given night of their lives, just as we cannot know for certain what happens in the lives of our neighbors or friends. What we do know is that they shared an uncommon love of art and one another that kept them emotionally tied until their deaths, despite the volatile nature of their relationship. My portrayal of a night of passion is, of course, conjecture, but given the nature of friendships between men and women, I believe it is well within the realm of possibility.

In your Author’s Note, you write about being in Paris and unexpectedly seeing a clay mask taken of Degas’s living face. What are some other highlights of your research trip?

There were many other wonderful moments, especially in the basement of the Musée d’Orsay. Aside from the startling mask, the most poignant objects were the series of Degas’s increasingly darker smoked eyeglasses, which highlighted for me how great his visual handicap was and its inexorable progression. Of equal importance was finding Degas’s last studio and apartment, where he lived and worked in his last years and where he died. I visited Morisot’s and Manet’s common grave at the Passy Cemetery; they rest together in the same grave with Suzanne, Édouard’s wife, and Eugène, Morisot’s husband and Édouard’s brother. This eternal connection cemented for me how intimately entwined they were in life. Cassatt’s footprint in Paris is less defined, but I was thrilled to look up at the Avenue Trudaine apartment and imagine her life there, as well as walk in her footsteps to her first separate studio, which, ironically, was situated on the site of Degas’s last studio.

What are you working on now?

Another historical novel. I can’t really talk about it as it’s still taking shape, but it will begin in the nineteenth century and take place in Albany, New York, Saint Lucia, Paris, and St. Petersburg, Russia.