One of your earlier novels, A Friend of the Earth, also tackled environmental issues. How long have you been interested in environmentalism and animal welfare? Like Dave LaJoy, did you experience a particular moment that awakened your interest?I suppose I've been interested in biology and the environment all my life. I grew up in suburban New York in a time when there was still abundant forest, and I roamed that forest with my eyes wide in wonder. (That forest, my own very specific one, has now been carved up into one-acre estates for some very nice but to my mind absolutely unnecessary homes.) Even now, after many years of living on the West Coast, I still find myself seeking out nature for solace and regeneration, whether it be the ocean down the street or the wild mountains of the Sierra Nevada. As for a particular defining moment, I can't point to one, though with regard to animal welfare I will never forget what Isaac Bashevis Singer had to say on the subject: "Every day is Auschwitz for the animals."

While your writing often addresses volatile issues, you never present clear ideological statements or endorsements of either side of an argument. Privately, however, you must have opinions on the issues you're writing about; has the process of justly representing both perspectives ever influenced or changed your own opinions?

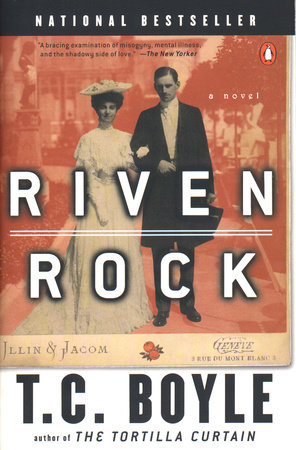

As I have said elsewhere, I do not believe that politics or advocacy and art make for an congenial mix. Fiction is meant to invite the reader to inhabit a space and contemplate a world and its issues as he or she will. It is not the place of the author to lead them by the nose (or any other body part, for that matter). That said, readers of my novels, from The Tortilla Curtain to A Friend of the Earth to When the Killing's Done, or stories like "Hopes Rise" or "After the Plague," should, I think, have an idea of what I believe in and what I stand for, though none of that should be relevant to his or her enjoyment of or engagement with a given novel or story.

Is FPA, the animal-rights activist group in the novel, inspired by any real-life counterparts such as the Animal Liberation Front? Do you think the aggressive and sometime violent tactics used by similar organizations ultimately help or hinder the cause of environmentalism and the humane treatment of animals?

Yes, I am quite consciously thinking of radical environmental groups here, just as I was back in 2000 with my novel about ecoterrorism and global warming, A Friend of the Earth. I can't say whether these groups are advancing or hindering the cause—on the one hand, organizations like Earth First! do bring attention to problems such as clear-cutting and do achieve results, though those results are often as much due to the efforts of mainstream environmental groups as their own; on the other hand, the attention is often negative, as their subversion of the rule of law may be construed by many as a sort of vigilantism. I ask myself, What would Edward Abbey say?

Within your exploration of the themes of population control and playing God, pregnancies and strong mother-daughter relationships figure prominently. How did the theme of motherhood and ecology come together for you?

As this is an interpretive question—or leads to interpretation—I will try to step around it. I very much like your pointing to some of the thematic links in the book, the unfolding of which I do hope will give readers pleasure. Of course, we do live on Mother Earth and we are animals who have been able to discover, through our keen intellects, the sole purpose of life as all other living things understand it: to reproduce.

It seems that there is an inherent conflict in Dave's opposition to slaughtering the rats and pigs, in that not destroying them will eventually destroy the native species; further, he relocates animals of his choosing to the islands. He believes that Alma is playing God, but don't his actions in effect do the same thing?

I will leave this for the reader to decide. The epigraph of the book, from Genesis, should give a clue. I wonder what our true relation to other creatures actually is—even the ones that parasitize us. Pity the poor mosquito (tick, leech, botfly) that only wants the very same things we do: to discover warmth, nutrition—yes, even love—and to raise a brood to inhabit the next and coming generation.

That nature suffers at the hands of humanity is a central point of the novel, but there are many instances of nature's overwhelming people; an example would be the significant role that the ocean plays in the plot. Why did you create this juxtaposition?

Who can step out the door without being overwhelmed by his own tenuousness in the scheme (or, rather, lack of scheme) of things? We are subject to random forces, and all our art, our beauty, our science and wisdom will come to nothing in the end.

Is there significance in the fact that Beverly and the rats arrive on Anacapa in the same fashion? Do you see humans as an invasive species, like the rats and feral pigs?

Again, this is a (wonderfully) leading question that I am not at liberty to answer. Pick up the globe, spin it on your index finger and answer for yourself. But isn't this the central conundrum of environmentalism? As Ty Tierwater, protagonist of A Friend of the Earth, says: "To be a friend of the earth, you have to be an enemy of the people."

Considering that you preface the novel with a quote from the Bible concerning man's God-given dominion over the natural world, and that Dave's boat is named Paladin after Charlemagne's Christian warriors, what connections do you see between the novel and religion?

Religion is voodoo, just as is science, its modern replacement. We live—and die—in a mystery, a mystery that both religion and science seek to address. But all we have, really, is our culture, our family, our art. Everything else comes in shades of black and blacker.

Alicia asks Alma, "What if we just left everything alone like the world was before us—like God made it. Wouldn't that be easier?" (p. 103). Is it reasonable—or even possible—to return the earth to its previously undamaged state? Does setting environmental ambitions so high doom all attempts to frustration and failure?

No. In fact, the restoration on Santa Cruz Island is one of the truly remarkable success stories of modern environmental activism. The indigenous fox, unique to this ecosystem, was a heartbeat from extinction when biologists discovered the final cause in a whole chain of man-made catastrophe—and the fox is now thriving once again. And all this, from imminent danger of extinction to recovery, came in the tiniest fraction of a wink of time. What can I say but hallelujah! The loss of any organism (smallpox?) is a loss forever, and we are all impoverished as a result.

There was a real-life attempt to eradicate feral pigs from the Channel Islands. Was it this endeavor that appealed to you as the basis for a novel?

Please see the response immediately above. Yes, it was this serpentine and, to a large degree, absurd concatenation of events that inspired me to explore the situation and write When the Killing's Done. I could not have done so without the cooperation, guidance and friendship of the naturalists and biologists involved, to whom I am deeply indebted.

What is your writing process? How long does it take to complete a novel, from initial idea to completed work? Do you work on multiple projects simultaneously?

My writing process is my life. Since I first discovered the miracle of fiction and of writing fiction, I have devoted myself to it with all my heart and soul. The world and our lives in it are mysterious and the only way I can begin to address that mystery is to create worlds of my own, to dream a dream and present it to you so that you can dream it too. As for the other two questions: 1) As long as it takes. 2) No. But then each project is different, each story or novel spinning out in its own orbit. My job is to follow it to completion and then follow the next.