-

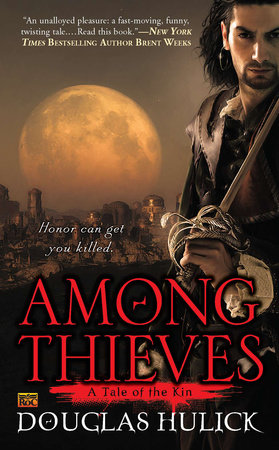

Published on Apr 05, 2011 | 432 Pages

Published on Apr 05, 2011 | 432 Pages

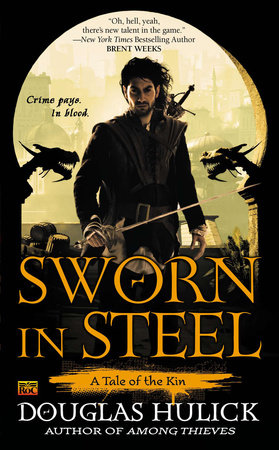

Drothe has been a member of the Kin for years, rubbing elbows with thieves and murderers in the employ of a crime lord while smuggling relics on the side. But when an ancient book falls into his hands, Drothe finds himself in possession of a relic capable of bringing down emperors-a relic everyone in the underworld would kill to obtain.

Author

Douglas Hulick

Douglas Hulick has been reading fantasy literature for almost as long as he can remember. He suspects this penchant for far-away lands of yore led, in part, to his acquiring a B.A. and M.A. in Medieval History, and likewise to his subsequent study and teaching of European Historical Martial Arts. It most certainly helped result in his authoring several novels, including Among Thieves: A Tale of the Kin.

Learn More about Douglas Hulick