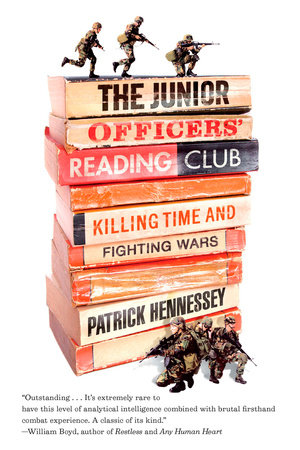

READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

Patrick Hennessey grew up on war stories. The son of an officer who had served in the first Gulf War, and named after a grandfather who was “a retired Cavalry officer [and] veteran of the Normandy landings” (p. xiv), he knew more than most cadets about what the future held when he began training at Britain’s elite Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Still, nothing could prepare him for the twinned horror and exhilaration that he would encounter as a platoon commander on the bloody fields of Afghanistan and Iraq.

After graduation, Hennessey is posted in the Grenadier Guards, Inkerman Company heading for Kandahar. “What we were dreaming of was getting out there and having a fight” (p. 11). Instead, they are detailed to train an Afghan National Army battalion. Hennessey’s military life up until now has been larded with periods of stifling boredom, but nothing as intensely frustrating as being confined to the safety of camp full knowing that the battle is elsewhere.

There Hennessey and his fellow junior officers informally come together in the eponymous club of the memoir’s title. All too soon they are scattered to postings in the thick of the action they’ve been hungering for, and some of them are wounded or killed. Thrust into positions of command, first in Iraq, then in Afghanistan, Hennessey continues to reflect on the questions that drew them together, and the often overwhelming responsibilities they’ve now assumed. What draws someone to the military life? How has the nature of warfare been altered by modern technology? Is the romanticism of war necessary? What’s the best soundtrack to a raid—gangsta rap or heavy metal?

In the end, Hennessey offers no hard answers, only the hard-won reflections of a man who comes of age amidst unbelievable violence, and—for his gallantry—becomes the British army’s youngest captain. “I can already feel both how glad I will be when it is over and how much I will miss it. How difficult to convey to anyone that matters something which they will never understand, and how little anything else will ever matter” (p. 249).

ABOUT PATRICK HENNESSEYPatrick Hennessey was born in 1982 and joined the army in January 2004. On operational tours to Iraq in 2006 and Afghanistan in 2007, he was promoted in the field to become the army’s youngest front-line captain and was commended for gallantry. Patrick is currently studying law and hopes to specialize in conflict and international humanitarian law. He lives in London.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONSHennessey frequently mentions experiencing boredom—both before and after he joins the military. Do you think that the men and women who are drawn to soldiering have a higher or lower tolerance for boredom? Do you think this affects their performance on the battlefield?Hennessey writes, “American books include The Day of the Locust and Brett Easton Ellis’s Rules of Attraction and Glamorama…We have these to remind us of the greed and the label cultures we defenders of the West are fighting to uphold” (p. 129). Does Hennessey believe that he is fighting a just war? Should a soldier who is willing to die and kill for his country believe in the truth of his cause?References to war movies as well as books and music permeate Hennessey’s memoir. Does popular culture have too much influence over the way that war is perceived and waged? Is this a recent development?Hennessey shares that he found other soldiers’ homemade “mini epics…more vivid, more real and more motivating than all the reportage and training and lectures in the world” (p. 95). How do you think their existence affects, if at all, the general public’s perceptions of the war?If you were going to war, what books would you want to have with you?Has the Internet alleviated or exacerbated the loneliness of war?Is it reasonable for the British and American armies to expect trust from the Afghan National Army troops?What is your take on the “hearts and minds” (p. 167) approach to war? How would you feel if soldiers from a foreign country were engaging in battle in your homeland?Besides Hennessey’s personal dislike of some of the embedded journalists, he feels that “they hadn’t earned the right to broadcast our [whining]” (p. 181). Do you agree with his assessment, or does the public have a right to know what is happening behind the scenes of a war?What do you make of the complete absence of female soldiers in Hennessey’s narrative?After feeling alienated from friends and family during his first R&R back home, Hennessey is happy to be back amongst comrades. Then, “the thought hit me: what if I’ll only ever be able to have real and honest conversations with [fellow soldiers] in the future? What if an invisible curtain has come down between me and all the people and things I thought I held close?” (p. 236). Are Hennessey’s fears justified? Does the government provide adequate support to returning soldiers?How does The Junior Officers’ Reading Club compare to other war memoirs that you’ve read?Were you surprised by Hennessey’s decision to resign from the army after the start of what promised to be an illustrious career? What would you have done in a similar situation?