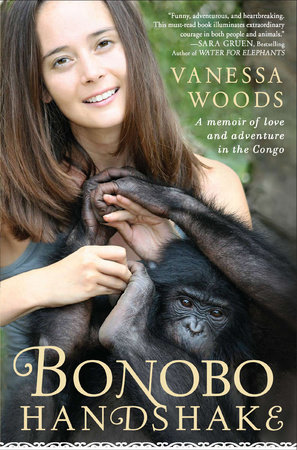

Author Q&A

Q. Even before you met Brian, you rescued chimps in Uganda and chased monkeys in Costa Rica. What is it that draws you to working with primates?

They remind me so much of humans. I know I’m not supposed to anthropomorphize, but especially with chimps and bonobos, they share 98.7% of our DNA, a lot of them is human. I feel like I can understand them, in ways I couldn’t understand a bug or a sea sponge.

Q. Currently, bonobos only live in Congo. Did they once occupy a broader habitat? If so, does their peaceful nature undermine their ability to survive amongst more ferocious species?

The Congo Basin, where bonobos live, was once larger, and when it shrank, bonobo range shrunk also. But bonobos aren’t threatened by other species, because they don’t share their habitat with chimpanzees or gorillas. I can’t imagine an encounter between chimps and bonobos would work out well for bonobos, so that’s lucky, and because they don’t have gorillas, a lot of the food they depend on, an herbaceous root, is theirs alone.

Q. You argue inconclusively with Brian about whether humans can learn “to be one people” (p. 156). How can the knowledge that all bonobos innately trust one another help to improve our own sense of trust?

When it comes to cooperation, which is essentially what trust is all about, we tend to think of it as cognitive. But what we found in our experiments was that cooperation is constrained by emotions, or tolerance. I think we have very strong emotions that prevent us from cooperating with people we see as being not like us. So people of different races, religions, sports teams—the lines are incredibly fluid. What we can learn from bonobos is that if we are more tolerant, then cooperation will come easier. We can be one people, but first we have to get our emotions under control.

Q. How have the released bonobos fared in their new home?

Great! The release has been a smashing success. No one has died, there have been two babies (conceived at Lola, so we are still waiting for our first wild birth), and the bonobos forage, roam their habitat, and live just as we hoped they would.

Q. What was it like going back to work with chimpanzees after your time with the bonobos?

Crazy. Chimps are so focused on the food and there is a lot less sex and play with chimpanzees. Physically they are so much more demonstrative: there are displays like pant hoots and they are more intimidating physically than bonobos. It is also interesting to sit down and watch chimps and how they interact with one another with male dominance and occasional aggression towards females. With bonobos it is just the opposite!

Q. You endured many difficult moments during your time at Lola ya Bonobo—from the deaths of Mikeno and Bolombe to the time you had to stand back and let a wildlife trader disappear with his kidnapped bonobo baby. Was there any point at which you just wanted to give up and leave?

No, because by then I had fallen in love with the bonobos. You never want to give up on someone you love. If anything, it made me more determined to keep going back. Even when I am in the ‘States I do everything I can to help bonobos. I spend a lot of my time writing grants and running the adoption program and just doing anything else I can.

Q. How it is that “chimps are endangered when they’re in Africa, but as soon as they are born in or smuggled into the United States, they lose their endangered status?” (p. 232)

That is a quirk of US legislation to enable biomedical facilities to test on them. The Humane Society is trying to get that status changed. What is really important is getting legislation to changed to chimps as pets, which is a much bigger problem than having chimps in biomedical facilities. Chimps in biomedical facilities is on its way out. It is very expensive and researches can’t use chimps for as much research as they thought. But it is way too easy to buy a chimp off the internet, and once they reach adolescence they become unmanageable.

Q. Based on the results of the study you initiated, it was discovered that “baby bonobos have incredibly high testosterone…; [And] the highest testosterone level found in the 2007 tests was in Masisi, a two–year–old–female” (p. 255). In general, we equate testosterone with aggression—and with males. Can you explain how higher testosterone levels correlate with the bonobos’ peaceful dispositions and their matriarchal social structure?

That is difficult because the testosterone actually correlates to sexuality. Testosterone isn’t linked to the matriarchal society or peacefulness of the group, and has more to do with their sex drive.

Q. Despite your misgivings about life in America, you and Brian fall “in love with North Carolina” (p. 237). Do you think that you will ever return to live in Africa?

We didn’t really live in Africa to start with. We would just go to visit to do research. Would I ever live in Africa? Who knows? I love the Congo and the Congolese but America is really my home now. And I’m lucky that every year I get to go back and visit Congo.

Q. What can the average person do to help save the bonobos from extinction?

Go to www.friendsofbonobos.org and they can adopt a bonobo. Just by buying the book will also help because part of the profits go to Friends of Bonobos. But the number one thing they can do to help bonobos is to talk about them. The greatest obstacle is people not knowing about them which makes it harder to save them in the first place.