READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

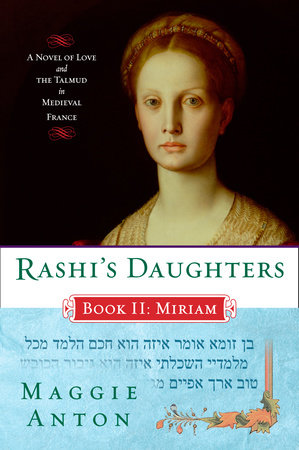

In the latter half of the eleventh century, the renowned scholar Salomon ben Isaac (or Rashi) breaks with tradition by teaching each of his three daughters, Joheved, Miriam, and Rachel, the intricacies of the Talmud. When Miriam loses her betrothed and childhood study partner, Benjamin, she feels as if her life has come to an end. And yet familial and societal pressures demand that she move past his death and choose a husband. So when handsome Judah ben Natan appears in the French city of Troyes, seeking a wife who is both modest and a scholar, it appears as if fate, or Le Bon Dieu, has only good fortune in store for the apprentice midwife.

But while Judah is a devoted Talmud scholar and quickly becomes a valued member of Salomon’s yeshiva, he wrestles daily with desires that conflict with his religion and the vocation he adores. Meanwhile, Miriam faces censure from her community as she becomes the first woman in Troyes, and one of the first in Europe, to perform brit milah—ritual circumcisions.

Rashi’s Daughters, Book II: Miriam picks up where its acclaimed predecessor, Rashi’s Daughters, Book I: Joheved, left off. InBook II, Maggie Anton continues to follow this fascinating trio of sisters as they defy the expectations and opinions that confine them, all while studying and revering their heritage through their devotion to the Talmud. This second installment of the Rashi’s Daughters series raises intriguing questions about women, sexuality, and tradition, while presenting a vivid picture of medieval France, and giving us insight into the timeless nature of loss, and of love.

ABOUT MAGGIE ANTONMaggie Anton was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California. Raised in a secular, socialist household, she reached adulthood with little knowledge of her Jewish religion. All that changed when David Parkhurst, who was to become her husband, entered her life, and they both discovered Judaism as adults. In the early 1990’s, Anton began studying Talmud in a class for women taught by Rachel Adler, now a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. She became intrigued with the idea that Rashi, one of the greatest Jewish scholars ever, had no sons, only three daughters. Slowly but surely, she began to research the family and the time in which they lived. Legend has it that Rashi’s daughters were learned in a time when women were traditionally forbidden to study the sacred texts. These forgotten women seemed ripe for rediscovery, and the idea of a book about them was born.

A CONVERSATION WITH MAGGIE ANTONQ. How did you gain your expertise on medieval Jewish life and, in particular, the lives of women during that period?A. I started my research three years before beginning to write. However, I have been constantly doing more research and incorporating what I’ve learned into what I’m writing. I actually changed the ending of Book I: Joheved the month before it went to the printer because I learned something new about medieval brit milah.

Q. What scene (or scenes) came to you first when you wrote Joheved’s story, and what scene(s) did you first visualize when you began Miriam’s story? How did your experience of writing Book I: Joheved differ from your experience of writing Book II: Miriam?

A. I first visualized what came to be the opening scene, with Joheved in bed with the cat, and also the scenes where Leah accuses the servant of stealing and where Rashi’s family learns to make parchment. For Miriam, I first visualized the night where she seduces Judah and he thinks she’s a demon. I had never written anything before Book I: Joheved, so I had a huge learning curve and it took me ten drafts. Book II was easier; I knew much more about plot and character development.

Q. What is it like working on Book III: Rachel (which is due out in bookstores in 2009), knowing that this is the last of Rashi’s three unusual daughters, and therefore the end of the trilogy? How hard will it be to leave this particular cast of characters and their extraordinary narrative?

A. Actually, I’m still learning lots of interesting things about medieval Jews as I research Rachel’s story, perhaps more than I can use. So depending on how successful the trilogy is, I may decide to write Rashi’s Granddaughters. In any case, I expect to keep studying Talmud for many more years, so Rashi and his family will continue to speak to me.ence of Ruth Stone’s poem “Romance” that I found inspiring the summer I read it over and over. And of course Virginia Woolf and Jane Austen.

Q. What other subjects are you interested in writing about? Do you have any other historical figures or time periods, and any other projects, in mind?

A. When I first decided to write Rashi’s Daughters, I had in mind another possibility, a historical novel about a woman mentioned many times in the Talmud, Rav Chisda’s daughter, who was married, in turn, to scholars who headed the two great Talmud academies in Babylon. I think the time period (500 CE) when the Talmud was redacted is also a fascinating one that few people know about. So I still want to tell her story.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONSThe author, Maggie Anton, opens her novel with a prologue that explains the social, political, and financial status of Jewish men and women in eleventh-century Europe. Also, it summarizes events that we might have read about, in detail, in Rashi’s Daughters, Book I: Joheved. For those who haven’t yet read Book I: Was this prologue enough? Did you find it difficult, or relatively easy, to jump right into Miriam’s story? (For those who have read Book I: Did you find any of Book II helpful in refreshing your memory?)

Similarly, Anton includes a glossary of terms at the end of her novel. Evaluate the glossary as a point of clarification—was it essential to your comprehension and enjoyment of the novel? Consider the ways in which Anton weaves the Hebrew words into her characters’ dialogue, and determine how many (and which) of the terms can be learned strictly through context

The Talmud is a collection of Jewish laws, followed by detailed commentary on those laws by different rabbis. (For more about the Talmud and the Torah, visit Anton’s website at www.rashisdaughters.com.) For readers unfamiliar with Judaism, how did the quotations from the Talmud’s tractates aid your understanding of the religion and its laws? Did any of the laws or customs surprise you? Which of these did you ascribe to the time period (eleventh century) and its tendency toward superstition?

While the narrative is set in medieval France, its subjects and themes are contemporary in nature. In particular, discuss Miriam’s multiple roles as midwife, mohelet, mother, and spouse, and Judah’s conflict between his homosexual feelings and his religious fervor. How can we, in the twenty-first century, relate to their predicaments?

One of the novel’s primary subjects is loss: loss of loved ones; loss of choice; loss of reputation; loss of property; etc. What is Anton saying about the nature of loss, based on the different ways she presents it in this novel? Develop a statement of theme by drawing on specific examples from the book.

Miriam’s marriage to Judah is one of compromise, but—as she observes at the end of the novel—out of her sisters, she is the only woman who is able to live in the same house as her husband throughout the year. In what additional ways is her marriage to Judah positive, if not ideal?

Additionally, consider whether you believe that Miriam was truly Judah’s bashert, or fated companion. Discuss also the betrothal of Isaac to Zipporah, daughter of Shemayah, and Joheved’s belief that if Isaac and Zipporah are bashert, there’s nothing she can do to stop them from marrying, and if they aren’t, there’s nothing that she needs to do. What does the rest of the book tell us about fate? In particular, does fate have anything to do with love?

Compare Judah’s relationship with Elisha to his relationship with Aaron, and discuss your reaction as each relationship progressed throughout the book. Did you expect Judah’s story to end differently than it did? Was there a point when you believed that Judah would act on his feelings? Do you think his final decision was made because of his strength of character, one of the trappings of God’s will, or simply a matter of chance?

Compare the eleventh-century attitude toward homosexual desire to that in the twenty-first century. People at the time considered the desire to be normal while acting on it was a sin. Did this surprise you? Why or why not?

Discuss the Notzrim, or Christian, characters in the book. How do Emeline de Méry-sur-Seine, Guy de Dampierre, Count Thibault (never seen, just mentioned), and the midwife Elizabeth help us understand the relationship between the Christian and Jewish communities in mid-eleventh-century Europe? How do these characters also serve to highlight the differences between these two cultures? How do their relationships help put history into perspective for us?

Discuss, too, the ways that the three sisters represent different female archetypes, in terms of physical appearance and in terms of character and spirit. Also, do you find any other uses of symbolism in the book?

All three of Rashi’s daughters are strong-willed, intelligent women, but Miriam appears to be the sister least ruled by her emotions, and yet, ironically enough, the most empathetic. Discuss the contradictory parts of Miriam’s nature, and how they combine to make her an interesting, vivid, and realistic heroine.

Finally, how does this book compare with other historical fiction you may have read? What makes it unique, and what have you learned from it?