READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

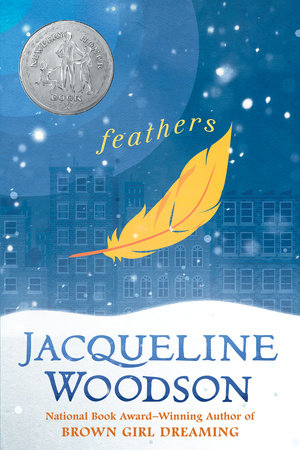

It’s been a long and snowy winter for Frannie and her classmates, and studying poetry can make it seem endless. “Hope is the thing with feathers …” That’s how one poem begins, but Frannie is not really sure what to make of it until a boy as white and quiet as the falling snow steps into her world. After a winter like this one, nothing will ever be the same again . . .

ABOUT JACQUELINE WOODSON

Born on February 12th in Columbus, Ohio, Jacqueline Woodson grew up in Greenville, South Carolina, and Brooklyn, New York and graduated from college with a B.A. in English. She now writes full-time and has recently received the Margaret A. Edwards Award for lifetime achievement in writing for young adults. Her other awards include a Newbery Honor, a Coretta Scott King award, 2 National Book Award finalists, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Although she spends most of her time writing, Woodson also enjoys reading the works of emerging writers and encouraging young people to write, spending time with her friends and her family, and sewing. Jacqueline Woodson currently resides in Brooklyn, New York.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Feathers is set in the 1970s. Although the civil rights movement has already happened, there still seems to be a deep divide between black and white in the story.

“There weren’t white people on this side of the highway. You didn’t notice until one appeared. And then you saw all the brown everywhere. And then you started to wonder.” (p. 16)

At one point when thinking about her neighborhood, Frannie says, “We have everything we need here.” Yet she also points out that it is an all-black community.

Frannie doesn’t seem to mind living the way she does, but her brother thinks about building bridges that would cross the gap between their neighborhood and the white neighborhood.

Trevor is the meanest kid in Frannie’s class, but she is also able to see glimpses of another side of him. She says, “I saw that, even though he was mean all the time, the sun still stopped and colored him and warmed him—like it did to everyone else.” (p 21)