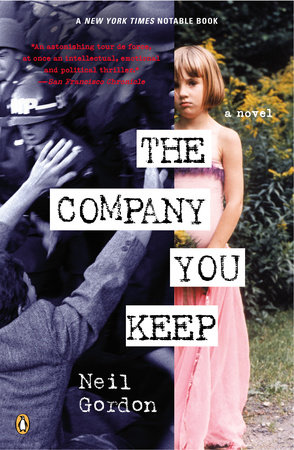

The Company You Keep Reader’s Guide

By Neil Gordon

INTRODUCTION

The Company You Keep is a strikingly original novel, both in the story it tells, of radical leftist fugi– tives unable to escape their pasts, and in the way it tells it, through a series of emails, written by different narrators, offering multiple perspectives on the same events. The emails are all addressed to Isabel Montgomery—daughter of former radical, James Grant, now a progressive lawyer in upstate New York—and are designed to convince Isabel to return from England to testify at a trial in Michigan. The nature of the trial, and indeed the true identity of several of the novel’s key figures, is kept secret for much of the book, building suspense as the story explores the past—the bombings, robberies, and revo– lutionary ideals of the Weather Underground—and casts an anxious eye toward the future.

A young reporter searching for a story discovers that James Grant is actually Jason Sinai, a prominent former member of the Weather Underground still wanted on murder charges stemming from the botched Bank of Michigan robbery in 1974 in which a guard was shot and killed. Now that he’s been identified, Jason must give up the relative safety he has painstakingly constructed for a perilous life on the run. He travels across America and into his own complicated past in a desperate attempt to elude the FBI and to explain the choices he made, decades before, to his daughter Isabel, who he abandoned in a New York hotel room when she was seven. In his first email to her, he writes: “I don’t deny that I was a bad parent. I’m not writing to excuse that fact. I’m writing, and so are the others, to tell you why.”

The novel is, in the broadest sense, about the meaning, morality, and efficacy of the Weather Underground. Throughout the book, the major characters look back on and debate the group’s actions, and whether or not those who remain fugitives should be punished. In a sense, the Weather Underground is on trial in the novel, both its aims—to stop the war in Vietnam and establish social and racial equality at home—and its explosive methods.

Jason himself argues that the Weather Underground was right about everything—race, the environment, the war—but that the lofty ideals and revolutionary fervor of the period ultimately led to no lasting changes, that American has in fact only gotten worse. The journalist Benjamin Schulberg thinks most of the weathermen were “pricks” but that their violent actions were justified by the illegal war in Southeast Asia, the draft, and the oppression of black Americans. For Benjamin’s girlfriend, Rebeccah, the Weather Underground’s actions are simply a matter of breaking the law. She argues that context isn’t relevant and that the fugitives from that time deserved to be judged just like any other criminals. Jason’s former lover Mimi still holds fast to the principles of the antiwar movement and argues that the Weather Underground deserve to be punished only if those who killed the students at Kent State and murdered Black Panther Fred Hampton are brought to justice. If all murder is wrong, she says, all murderers, including those in the government, should be held accountable. But the author Neil Gordon ultimately invites readers to enter this debate and decide for themselves how to view the actions of the Weather Underground, both as it’s represented in the novel and historically.

In a masterful blending of fact and fiction, The Company You Keep brings one of the most tumultuous eras in American history vividly to life, imaginatively examining the morality and consequences of the attempted revolution and the motivations, regrets, and emotional costs of living underground for those who fought it.

Neil Gordon is the author of two previous novels, Sacrifice of Isaac and The Gunrunner’s Daughter, as well as the forthcoming You’re a Big Girl Now. The author of numerous reviews and essays, he is literary editor at The Boston Reviewand, currently, a professor of literature at The New School in New York and The American University of Paris, where his is also vice president and dean.

Q. Why did you choose to tell the story of The Company You Keep through a series of emails and from a variety of perspectives?

This wasn’t my original structure for the book. I began writing it in one single voice, Jason Sinai’s, and then Mimi Lurie’s imposed itself on me and I found myself splitting the narrative between the two. Slowly, the other voices crept in, one after the other, and, in time, I understood why. It was simply that this is how the story came to me.

I was, during the first two years of writing the book, traveling extensively to find and talk to the people who lived the reality of the Vietnam war—whether members of the anti–war movement or veterans of the war itself—and in each interview I was hearing a different version of the same history from a different perspective and in a different voice. And in each, there was the same element of exhortation: to each of these people, it was naturally very important that I believe in their version of history. All of these people were slightly older than me, and so I felt myself very much in Isabelle Grant’s position: being lectured on American history by her elders and betters. From there, it just became a natural choice to reproduce, for the reader, this strong experience of listening to many different perspectives from many different voices.

Q. Why were you drawn to write a novel about the Weather Underground? Were you aware of radical leftist groups when you were growing up?

For people my age, and older than me—the generation who lived through Vietnam—the Weather Under– ground was a very potent part of our experience of the 60s and 70s. It’s hard, today, to explain exactly why. In order to do so, I’d have to reproduce the experience of living through the Cold War days. The vicious years characterized by Joe McCarthy and his persecutions of supposed American “communists” were just a few years behind us. COINTELPRO—the policy of internal policing, harassment, and jailing of left–ist Americans—was an ongoing governmental program. The Civil Rights movement, and the escalating protests against the war in Vietnam, had revealed a level of brutality in our government’s treatment of its citizens that was shocking to anyone who believed in American democracy: you only have to look at the Freedom Rides in the south or Kent State to see how awful it was for those of us who had been brought up to believe that we lived in the greatest democracy of human history to see that, as Donald Duncan said in Ramparts Magazine about Vietnam, that “the whole thing was a lie.” And Vietnam itself—the fact that our government had the right to force young Americans to go and participate in a brutal, unjust, and illegal war, was a reality that the entire draft–age population of the country, and their families, faced on a daily basis. We could watch the reality of terrifying firefights on television and across this country there were young men—boys, really—who knew that in a few short months it could be them being forced to carry a gun and shoot it at other human beings or be shot themselves, maybe have their right leg torn off, or their arm, or be hit fatally in the stomach and die in unimaginable agony. These were real, tangible possibilities. And, as the mobilization against the war in Vietnam grew larger and larger—as national figures like Martin Luther King and Walter Cronkite came out against the war and Americans of every generation joined the opposition— the response of the Johnson and Nixon administrations was to grow increasingly militant and increasingly oppressive, which made it clear that the principled, legal, and democratic opposition to the war by millions of American citizens was having no effect whatsoever.

So when a group of young people came forward and said that it was no longer enough to continue to lead normal lives, interrupted by the occasional march on the Pentagon; that we simply could not go on as citizens of this country; that the fight against the slaughter taking place in Vietnam and against the continu– ing oppression of African Americans, had to become the center of our lives, and that the traditional tools of revolution—the tools, after all, that the American revolutionaries had used to create this country—were now the proper tools of this struggle, many, many people responded to this with a great deal of sympathy.

I don’t mean to say that they were right—there are a lot of reasons to debate whether the Weather Un– derground was right in any of their analyses, or any of their actions. The use of violence in political protest is not an easy subject to resolve. In the contexts contemporary to Vietnam, there was political violence being practiced all over the world: South Africa, Cuba, Palestine, Algeria, and in each case a different analysis pertains. In the American context, I’d say, in fact, they were likely wrong, and that the paradigm for effec– tive protest was offered by Martin Luther King, not by the Weather Underground. But that’s a debate, and anyone who goes honestly into it will find themselves having to listen carefully to arguments on both sides before they come to their own position.

Q. What particular challenges come with writing fiction about actual historical events, mixing fact and imagination?

Well, getting it right is the first challenge. It requires you to learn the history in its most obvious sense— what happened, when—and then in a deeper sense: what did those events actually mean to the people around them. You have to understand the events as they were understood by the people who lived them, not as they were understood in retrospect by historians. We know, today, that the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolu– tion was based on a lie: that the attack on the USS Maddox in the Tonkin Gulf that gave the Johnson ad– ministration the right to deploy our armed forces in Vietnam—the attack actually never happened. Bush had his lie about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, Johnson had his lie about the attack on the USS Maddox. But who knew what, and when? The resolution was not repealed until 1971—by then, thousands of Ameri– cans had gone to fight in what they thought was a justified war. This is what a novelist must understand and reproduce. And it’s not just on one side: I have a profound, abiding respect for any American who went to fight in Vietnam. You come to that respect, though, by understanding not the history, but how they lived the history, what they believed and how they came, as individuals, to be there in Vietnam.

But I think the most profound challenge is one of judgment. When a novelist writes political characters, their job is not to judge right or wrong but to try to live the experience of their characters with the deepest sympathy possible. During the writing of this book, I met and became friends with people who had killed people in Vietnam and people who had broken the law protesting the war in America. None of them have simple ideas about what they did then. I can’t think of a single veteran I’ve ever met who still fully believes that the war was justified; nor can I think of more than one or two veterans of Weather who don’t question what they did then. I was even once invited to a university class where the professor, a Vietnam veteran, had invited a leading member of Weather give a guest lecture so his students could understand both points of view. People are complex, and it’s a novelist’s job to explore that complexity.

And history is complex. As a novelist, I want to be able to experience what my Vietnam veteran friends lived, just as I want to be able to experience what their opponents in Weather lived. Neither of them were right. Both participated in terrible things. And I could have been either of them. As a novelist, it’s not my job to judge people, but to try to inhabit their experience and make it alive for my readers. If they wish to judge, that’s up to them.

Q. Did you base any of your main characters on real people? Would the journalist Benjamin Schulberg be the character you most identify with?

No, none of the characters are based on real people. They’re all invented, and when I wanted a real per– son in there, well, I put a real person there. I don’t identify strongly with Benny—I like him, and maybe he has my sense of humor more than any character—I’m also kind of a jerk. But the character I live the most closely in this book is Mimi Lurie. Not in her experience, of course, but in her emotions.

Q. The novel is pervaded by a kind of lyrical nostalgia and at times regret. What is appealing to you about telling the story from the vantage of the present, looking back on the past?

There is a great pathos to the history of the American left. Its death is the saddest story of our country. Throughout our history, men and women have stood up for the highest ideals of democracy: fairness to all, opportunity for all, and the moral principles that guide our country. And all have been, to a degree, shot down: whether really shot down, like Fred Hampton, or imprisoned, like Eugene Debs, or persecuted, as

is happening now to Norman Finkelstein. It’s a terribly sad story, and when we look at it from the vantage of today, where America, for all its power, has near–pariah status throughout the world, it can only make us long for the lost ideals of our country, and think with great nostalgia of those who risked their lives to defend them.

Q. Do you see many parallels between the Occupy Wall Street protests and the protests of the 1960s and 70s?

I don’t see a parallel, but I see a strong connection. This is hard to explain, but I’ll try. The main criticism of the Weather Underground by people of the left is that it broke up the movement against the war in Vietnam. Prior to 1969, the SDS—Students for a Democratic Society—had been huge and peaceful movement in America.

But when Weather broke up SDS, which they did violently, undemocratically, and with huge cruelty, they destroyed what could have been an enormous, powerful progressive movement in this country—so the argument runs. And from my point of view, the American left never recovered. From then on it was charac– terized by factions, by an inability to agree on priorities and actions, by ineffectiveness, and by high levels of internal dissent.

And we see that’s true today, too. Such a simple thing the Occupy movement is saying—such a simple kind of injustice they’re pointing out: that the riches of our country are being reserved for the very few, and our elected government is not representing the rest of us. But why is it only being said in Zucotti Park and not in the Capitol Building? Why do the conservative and ultra–conservative movements in our country manage to run candidates and influence policy and law, while the left–wing movements have neither influ– ence nor power? I believe that when Weather broke up the national SDS movement, it contributed centrally to the lasting decline of the American left, which we see today in how correct, but ultimately how small and powerless the Occupy movement is.

Q. At the end of the novel, Billy Cusimano muses: “With parents this good—parents like Jason, Molly, the Osbornes, McLeod, and even, in his own small way, Billy himself—maybe it would be their children who’d at last, at long last, do better with this rotten, corrupt world” (p. 403). Do you feel hopeful that future gen– erations will succeed where their parents failed? Where do you think the United States is headed politically?

I don’t know where we’re headed politically—it’s hard to feel that it’s anywhere good, but I am just a novel– ist, not a political analyst. What I do know—because I can observe it—is that the generation of my children, which is roughly the same as the generation of Billy’s children, is the heir to enormous social advances with roots in the anti–war movement and cultural revolution of the 60s and 70s. When my children speak to me today about a friend they’ve just met, they never think of telling me if they’re black or white or straight or gay. They are free of so many of the prejudices of the 50s that continue to plague our country. Ask my kids if they think gay marriage is a hot topic? They think it’s absurd: of course same sex couples should have the same rights as heterosexual couples. So there is reason for hope in the social progress that we’ve made since the Vietnam days.

But political progress? It’s hard to imagine that there’s been any at all. And it’s hard to imagine a future in which this is going to change radically. Something profound about America was summed up for me last year when I had the chance to visit the Shatila refugee camp in Beirut. A middle aged Palestinian man in– vited me into the school he runs for tea. He had lived his entire life in the camp, which is not a nice place to– day, and has been a much less nice place in the past, particularly during the Lebanese Civil War when it was the site of slaughter by Israeli and Lebanese Christian forces, both backed by our country. “I hate America,” he told me. “But I like Americans.” That sums up the strange, paradoxical status of our country.

Q. Have you encountered any criticism of your novel based on political reactions? Have any former mem– bers of the Weather Underground—Bill Ayers, Bernadine Dohrn, etc.—responded to the book?

I won’t talk about the reactions from participants in the history I wrote about—that would be a violation of their privacy. Their responses were thoughtful and generous. There’s one thing I got wrong in the book, and readers corrected that. I appreciate the corrections and feel bad about the error. The most interesting thing to see is the right–wing reactions on the web, which take some finding because they’re very marginal. There are wounds in this country from Vietnam that will never heal—Jane Fonda’s visit to North Vietnam in 1972, for example. There are millions of people in this country who will never, ever forgive her for that. In some places, my book twisted a knife in those wounds and there was reaction. And then, there have been very thoughtful and interesting reviews on the left, in magazines like Dissent and Counterpunch, where smart people have taken the book as the opportunity to reconsider the real questions raised by Weather in the light of contemporary American politics, and those have been, of course, very gratifying to read.

Q. During his 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama was widely criticized by the right for his associa– tion with Bill Ayers. What’s your sense of how the Weather Underground is regarded now?

That’s pretty interesting. On one hand, Ayers is a retired distinguished professor in the University of Illinois system—a state system, mind you. This is a huge accomplishment. And then, he’s an invited speaker all over the world—all over—on issues educational and political. This means that there are people all over the world who may or may not agree with Ayers’ political past, but who think of him as an important, reputable, and expert person who deserves to be listened to.

On the other hand, there are people who say that Ayers’ past in the Weather Underground is domestic terrorism, and that even talking to him in a Hyde Park living–room is proof of some kind of disloyalty—that Obama had discredited himself by having met and talked to Ayers. And this about a President who was elected by a majority of our country—our democratically–elected, legitimate, President of the United States.

That shows how toxic the Weather Underground is in today’s political spectrum. But it shows some– thing far more important than that, too. It’s hard not to ask oneself: which are the real Americans in this question? If Ayers is a domestic terrorist, why is he not in jail today? He stands convicted of no crime, of no illegality, and thousands of our fellow citizens want to listen to what he has to say. Do we believe in the First Amendment or don’t we? Do we believe in our court system or don’t we? Do we believe in the demo– cratic process or don’t we? And if we do: then why do we try to try to shut Ayers up and try him in the public court when he has been cleared in the real court; why do we try to delegitimize a President that our fellow citizens have elected in the democratic process?

Q. In a long speech to Benjamin, near the end of the novel, Jason says: “in every possible way—race, war, the environment—we were right. Our government has rolled over that dream, every single day since the sixties. Every single day it’s gotten worse. . . . If this country had made the three central ideas of the Port Huron Statement—antiwar, antiracism, and anti–imperialism—the law of the land, today we’d be living in a safe, just, and prosperous society” (p. 365). What’s your own view of the Weather Underground, the posi– tions and the actions they took? Would you essentially agree with what Jason says here?

What Jason says here is indisputably true. If you read the Port Huron Statement—the basic statement of political values of SDS, mind you, and not written by the Weather Underground— you’ll read a sane, sober, literate and highly principled document by smart, educated, young people. There’s nothing in the Port Huron Statement that’s not true today, and Jason’s words are a simple statement of fact. Antiwar: from Vietnam to Iraq, this country has squandered its riches on useless ideological wars and impoverished its core commitments to education and social services in the process. Imagine the public school system we could build with the amount of money we spent in one week in Iraq. Imagine the kind of health care services we could provide to all Americans with a fraction of the money we spent in Afghanistan. I now live in France where every citizen has full health coverage and a free education from kindergarten through to their Ph.D. Why don’t we? Antiracism: the profound racism of our country—the marginalization of African Americans, Latinos, and other minorities—continues today to violate everything we believe in and everything we stand for. And as for anti–imperialism, people who have fought for their freedom all over the world see us as hav– ing supported oppressive regimes everywhere: the Somazistas in Nicaragua, the Israelis in Palestine and the Maronite Phalange in Lebanon, the Shah in Iraq, Pinochet in Chile . . . the list goes on and on. Remember, we even supported Saddam before we decided he was our enemy. So it’s a very simple statement, and very true.

But personally, no, I don’t think highly of the positions the Weather Underground took and I don’t believe that political violence was an effective or appropriate tool in the American context. As a novelist, I understand. As a citizen, though, I think that they were wrong in virtually everything they did. I’m not saying that I might not have joined them in that error—I may have, though I like to think that then, as now, I would have been more open to the example set by Martin Luther King. But in retrospect, we can see that they were very badly in error.