READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

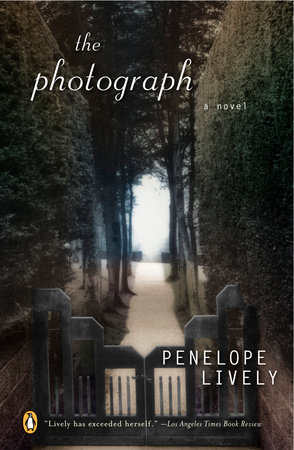

Booker prize-winning novelist Penelope Lively has been praised for creating characters whom readers are reluctant to part with and for a Jamesian complexity that is at once intellectually compelling and emotionally riveting. In The Photograph, her thirteenth work of fiction, she takes her narrative mastery and psychological insight to new, and seldom achieved, heights.

The Photograph is an unflinching and unforgettable story of the many ways the past intrudes upon the present and the present alters the past. When Glyn, a landscape historian, stumbles upon a photograph of his deceased wife, Kath, holding hands with another man, his understanding of the past is “savagely undermined.” Reading the past, uncovering and deciphering its strata, is his stock in trade, but now it is his own personal landscape, and the history of his marriage, that he must reinterpret. He veers from emotional vertigo to an obsessive need to know what kind of woman his wife really was. Why did she have an affair? Did she have other lovers? Was their whole life together a lie? His search takes him back into his life with Kath, and her absence becomes the most powerful presence in his life, rising up before him, speaking to him, leading him to discoveries that reveal much more—and much more disturbing truths—about himself than about his wife. Though dead, she is the novel’s most eloquent character, the still center around which the lives of all the other characters begin to swirl. Who was she, this beautiful woman who seemed to draw and hold the gaze of everyone who saw her, who seemed carefree and clearly happy, a burst of color and uncontainable energy?

And why did she have to die so young?

A taut and suspenseful psychological narrative, written with Lively’s unmistakable nuance and insight, The Photograph is above all a profoundly moving meditation on the mysteries of time, memory, and the instability of the past.

ABOUT PENELOPE LIVELY

Penelope Lively grew up in Egypt but settled in England after the war and took a degree in history at St Anne’s College, Oxford. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and a member of PEN and the Society of Authors. She was married to the late Professor Jack Lively, has a daughter, a son and four grandchildren, and lives in Oxfordshire and London.

Penelope Lively is the author of many prize-winning novels and short story collections for both adults and children. She has twice been shortlisted for the Booker Prize; once in 1977 for her first novel, The Road to Lichfield, and again in 1984 for According to Mark. She later won the 1987 Booker Prize for her highly acclaimed novel Moon Tiger. Her novels include Passing On, shortlisted for the 1989 Sunday Express Book of the Year Award, City of the Mind,Cleopatra’s Sister and Heat Wave. Penelope Lively has also written radio and television scripts and has acted as presenter for a BBC Radio 4 program on children’s literature. She is a popular writer for children and has won both the Carnegie Medal and the Whitbread Award.

A CONVERSATION WITH PENELOPE LIVELY

Could you describe the genesis of The Photograph? How did the story and characters come to you?

I have had to empty two family homes during the last few years—first, the house that had been my grandmother’s since 1923, and then my own country home, which we had lived in for over twenty years. Both were large houses, so that nobody felt constrained to throw things away. As a consequence there were cupboards and drawers and shelves piled high with papers. Going through these, I kept coming across some letter or document that surprised me or conjured up the past in some way. I can’t say that I ever came across any revealing photograph, or indeed anything else of that order, but I kept thinking how betraying such detritus can be—potential time bombs in a file or at the back of a drawer.

So that was the initial prompt for The Photograph. After that, it was a question of hunting for the narrative and the characters. I know that I wanted a central figure who was the key to the whole story, but who was not there anymore, and who would be seen entirely through the eyes of others. A woman, definitely—someone compelling. I’m intrigued by the way in which physical appearance can often direct a person’s life; things happen differently for a beautiful woman than for a plain one. So Kath arose—an exceptionally attractive woman for whom perhaps her looks were a disabling factor.

Do the themes of time and memory, the changing relationship between past and present, have an especially deep hold on your imagination?

Yes, indeed. I’ve always been fascinated by the operation of memory—the way in which it is not linear but fragmented, and its ambivalence. We cannot do without it, but it can also be a liability. In different ways, this has been the theme of several of my novels—Moon Tiger, Treasures of Time, Passing On—but I keep seeing new ways of exploring it. The Photograph is concerned with the power that the past has to interfere with the present: the time bomb in the cupboard.

When Glyn finds the envelope containing the photograph of Kath and Nick, he wonders if Kath had planned this moment. Is it purely chance that he discovers the photo, or are we meant to feel that he was fated to do so?

It seems to me that everything that happens to us is a disconcerting mix of choice and contingency. We make choices but are constantly foiled by happenstance. It is indeed by chance that Glyn comes across the photograph; he might not have done so then, and perhaps not at all. A fateful accident—both that he found it, and that it survived for him to find.

A landscape historian seems the perfect profession for Glyn. Is this an area you’ve always been interested in, or did you research the subject specifically for the novel?

I think that Glyn is a character who has been waiting to happen to me. I have long been interested in landscape history, and when younger and more robust I used to do much tramping of the English landscape in search of ancient field systems, drove roads, indications of prehistoric settlement. Towns and cities, too, which always retain the ghost of their earlier incarnations beneath today’s concrete and glass. So I do know a fair amount about landscape history, and therefore what Glyn’s career pattern might have been and how he might see the world and think about it. I do like to embed a fictional character firmly in an occupation. After all, we are all of us driven by work—it occupies our days and directs our lives. But if you are writing about a character’s working life you must do so convincingly. Research. Background work. Libraries—plus a great deal of asking around. I have written of historians more than once, an archaeologist, a paleontologist, an anthropologist—as well as an editor, the proprietor of a plant nursery, a librarian, a schoolteacher, and various others—all of which has involved fascinating and enlightening inquiry into how other people’s lives are run. You learn a lot, writing fiction.

Why did you choose to write Polly’s chapters in the form of dramatic monologues?

I wanted Polly to stand apart from everyone else—a sharp, distinctive voice. She is younger—another generation—and her vision of events is significantly different. The natural thing therefore seemed to be to let her speak for herself, very directly. That kind of monologue is something of a challenge—finding the right note, the right language, but also exhilarating. I enjoyed Polly.

How do you see The Photograph in relation to your other novels?

Every novel generates its own climate, when you get going. In The Photograph, I was trying to write a book that would be multifaceted, in a way that I have not really done before. Conventional forms of narrative allow for different points of view, but for this book I wanted a structure whereby each of the main characters contributed a distinctive version of the story. I have experimented before with contrasting evidence—the sense in which different people experience or interpret an event in completely different ways (in Moon Tiger, for instance) —but this method is a new take on that. The pleasure of writing fiction is that you are always spotting some new approach, an alternative way of telling a story and manipulating characters; the novel is such a wonderfully flexible form. When I was planning The Photograph—always a lengthy process for me, with a year or two of making copious notes—I knew that this book needed several voices, quite possibly contradicting one another, so that it would reflect the way in which there is never any single truth about any person, or about any sequence of events, but as many as there are observers or participants.

The Photograph says much about the shifting nature of past and present. Do you find it to be true that the present and the past are continually influencing and changing each other?

We all need a past—that’s where our sense of identity comes from. Even quite small children build up a picture of their origins. Getting to know someone else involves curiosity about where they have come from, who they are. Equally, we require a collective past—hence the endless reinterpretations of history, frequently to suit the perceptions of the present. The present hardly exists, after all-it becomes the past even as it happens. A tricky medium, time—and central to the concerns of fiction.

What writers have been most important to your own work?

I’m tempted to say, everyone I have ever read, because it is only through reading that you discover your aversions and affinities. When I was young, the favored writers—on my side of the Atlantic—were those who never used one word when ten would do, practitioners of a florid, verbose, expansive style such as the Sitwells (all three), Norman Douglas, Christopher Fry. I read dutifully but uneasily. And then I discovered writers like Henry Green, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Elizabeth Bowen, and others, and realized that what I admired was accuracy—the use of the perfect word, the exact phrase. Accuracy and economy.

Since then, I have just read and read—but, that said, I suppose there is a raft of writers to whom I return again and again, not so much because I want to write like them, even if I were capable of it, but simply for a sort of stylistic shot in the arm. Henry James, Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, Saul Bellow, John Updike, Patrick White, Alison Lurie, Carol Shields, Barry Unsworth, Evelyn Waugh, Anne Tyler, William Trevor . . . and others. Affinities and addictions change over time, too—you can fall out with a particular writer, and fall in with a new discovery. All I know for certain is that reading is of the most intense importance to me; if I were not able to read, to revisit old favorites and experiment with names new to me, I would be starved—probably too starved to go on writing myself.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS