READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

INTRODUCTION

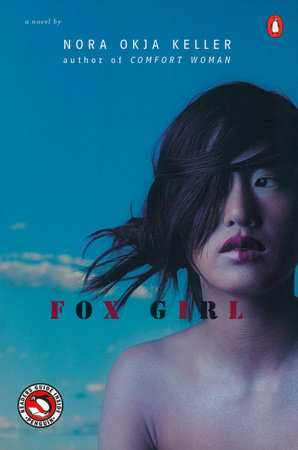

Nora Okja Keller isn’t one to shy away from difficult subjects. Her first novel, Comfort Woman, dealt with the experiences of women forced into sexual slavery for the Japanese military during World War II. Keller’s latest novel, the second installment of a planned trilogy, takes a hard look at the complex history between Korea and the United States.

Set in a military camp town in 1960s Korea, Fox Girl is about the lives of mixed-race teenagers—literally products of the Korean War—coming of age in a seemingly dead-end world of poverty, vice, and despair. Known as “throwaway children,” they’re alienated from a Korean society that values purity above all, and abandoned by the American soldiers that fathered them.

In America Town, cultures converge and clash. Coca-Cola sits on store shelves next to kimchee. In the school run by missionaries, young “half-halfs” are taught that America is better than their homeland. Meanwhile, even as the civil rights movement gains momentum in the U.S., in America Town white and black GIs are segregated. The Korean prostitutes and bar girls pander to all of them, naively believing that if they play their cards right, one will propose marriage someday. Kids hustle black-market goods and pimp their own mothers, hoping to make enough money for a ticket to America. In all these schemes, the goal is the same: escape.

Hyun Jin, one of the three main characters in the novel, is determined to get out of America Town and break free from the brutality of her own existence. After being disowned by the parents who raised her, she descends into an abyss of self-loathing, prompting her to follow her best friend Sookie down the path of prostitution. When Hyun Jin sells her virginity in a transaction that essentially amounts to gang rape, she finally understands what Sookie meant when she instructed her to “[let] the real self fly away.” Becoming numb to what she sees as her destiny allows Hyun Jin to endure it.

As she slowly learns the details of her history, Hyun Jin begins to recognize the precariousness of all relationships and forms a sort of family with Sookie and their teenage pimp, Lobetto. Devastated when she miscarries her own baby, Hyun Jin clings fiercely to Sookie’s unwanted child, promising to raise it as her own, determined to break the cycle of abuse and abandonment.

Fox Girl is a dark, often relentlessly graphic story that challenges the reader to extract its ultimately redeeming message of survival and transformation. Betrayed by her family, her society, and sometimes her friends, Hyun Jin must do whatever she can in order to survive, and in the process she finds that her strength of will transcends what she felt was her fate, what she thought was in her blood. Like the mythical fox that turns itself into a girl, Hyun Jin is determined to transform the ugliness of her life into beauty.

ABOUT NORA OKJA KELLER

Nora Okja Keller was born in Seoul, Korea, and now lives in Hawaii with her husband and two daughters. She received the Pushcart Prize in 1995 for “Mother Tongue,” a piece from her first novel, Comfort Woman, winner of a 1998 American Book Award.

A CONVERSATION WITH NORA OKJA KELLER

How have the different audiences in Korea and in the States responded to Fox Girl?

Since I write about a time and place that I am not personally familiar with, I sometimes worry about authenticity; there is only so much research you can do. So when Fox Girl first came out and I started to meet the first readers of the book, I half expected to be denounced. Actually, I think that’s the fear of most writers, no matter how established.

At the start of the book tour, I was scheduled to do a radio interview with an African-American man who had been stationed in Korea at the time Fox Girl was written, and I thought “uh-oh,” here it comes: he’s going to tell me I got it all wrong. But when I walked into the studio, the first thing he said was, “I’ve been waiting thirty years for someone to tell this story. I feel like it’s a part of my history.” And he shared with me two photo albums full of his time in Korea, full of America Town. He even pointed to one picture of a group of biracial children and said, “Look, there’s Lobetto! Any one of those kids could be him!”

That experience touched me deeply, and reminded me to trust that if I do the research and write from the heart, the writing will lead me true.

As the daughter of a Korean mother and German-American father, did personal experiences of your own help you develop your characters? Which character do you identify with most, and why?

Every character is born inside the writer, from personal experiences, from different aspects of the personality. And I do start by trying to imagine how I would react if I were in the same situations that I place my characters. But as each character develops, they take on a life of their own, one that is very different from mine. So, while some of the characters in my novels are hapa, or mixed-race, as I am, they don’t necessarily represent “me”—my history or my feelings—in any way.

How did you come to focus on the relationship between Koreans and black GIs as opposed to GIs of any other race?

In the late sixties and early seventies, racial tensions—between black U.S. servicemen and white U.S. servicemen, and also between black servicemen and the local Korean residents—were at their height in the segregated America Towns. The racial lines were so sharply drawn that the black soldiers and the women who worked in the all-black bars risked being beaten if they tried to “cross over.”

The Korean prostitutes were highly sensitive to the racial divisions among the soldiers, just as they had to be sensitive to all things American. And because white servicemen outnumbered black servicemen, most bars and most prostitutes were “white only,” which perpetuated the discrimination. The Koreans living in the camptowns were mimicking and then assimilating the racist language and attitude of white soldiers towards blacks.

The people existing at the lowest rung of America Town’s social hierarchy were the “GI girls” who serviced black soldiers. The children from these unions weren’t even on that ladder; they were invisible, considered neither Korean nor American. I wanted to acknowledge their existence, to give them a voice in Fox Girl.

Will your next book focus on Myu Myu, or will we see any of the same characters from Fox Girl?

The next book will be a sequel focusing on Myu Myu—and yes: some of the characters from Fox Girl will reappear, though perhaps not in the same form; we see people from new perspectives.

Was it difficult to write from the perspective of a very young girl? Are there specific processes you employ to reach that point of view in your writing?

No, since I was a young girl once—long, long ago—and I keep that girl within me still. Also, I have two daughters who keep that perspective fresh.

How has living in Hawaii (as opposed to the mainland) affected your writing?

Hawaii has a strong tradition of “local” literature, where writers explore what it means to belong to this place, and how you can retain your ethnicity and culture and still be “local.” Also, an island is small; pretty much everyone in Hawaii’s writing community knows or knows of everyone else. We know where we all live, and it’s all close by.

Which makes it easy for beginning writers to find the support to keep writing. A dozen years or so ago, I was lucky enough to hook up with a great writing group called the Bamboo Ridge study group. One night a month, we try to get together to talk about the work we are doing (or not doing), about Asian-American writing, about local literature—and to drink wine.

What are your thoughts on the state of Asian-American literature?

I went through high school and most of college without reading a single book written by an Asian American. I wasn’t even familiar with that term; in the seventies and eighties, we were called “Oriental.” Then in 1986, I read Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston and went: “Whoa!” Here was a person writing close to home—my home. That book opened up a hunger in me for other books written by Asian Americans, and what I found was a hundred year history of Asian-American literature that was going unacknowledged.

Now, twenty years later, Asian-American literature is being offered at some high schools and most colleges across the nation. And Maxine Hong Kingston is a staple in American Literature courses.

After Kingston, who was the “It” Asian in the seventies and Amy Tan in the eighties, there has been a proliferation of Asian American authors from all ethnicities—Korean, Vietnamese, Filipino, as well as Chinese and Japanese—so that our national understanding of what is “Asian American,” and by extension “American,” has had to expand. And that’s always a good thing.

Who do you see as your intended audience?

I don’t think about audience when I write. If I imagined thousands of eyes reading each word as I wrote it, I think I would put the pen down right then and there.

What writers do you most admire? Are there any specific books over the years that have been especially formative in terms of your development as a writer?

I had a solid education in the American classics, which when I was growing up meant: Steinbeck, Faulkner, Whitman, Hemingway. Each one of those writers influenced me in some way, but I couldn’t visualize becoming a writer myself until I read people who were more like me: female, non-white, and alive. So, as I mentioned earlier, Kingston opened up this awareness of possibilities for me. Then there was Cathy Song—a Korean-Chinese poet from Hawaii!—who has since become a close friend. And, of course, there are those writers who just seem to exist on a higher plane: Toni Morrison, Isabel Allende, Gabriel García Márquez.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS