READERS GUIDE

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. When Hélène first arrives in Saint Homais, Father William talks about her being “uncommitted,” and asks her if there’s anything he should know that would prevent her from being active in the church. What do you think would have happened if she had told the priest the truth?

2. Discuss the various ways in which the people of St. Homais react to the news of the murder charges against Hélène, and why.

3. In the end, do you think Hélène ever achieves clarity or resolution? Has she made a new beginning? Is it ever really possible to leave the past behind?

4. Nathan wants Hélène to accompany him on his dealings because “people trust a man when he is with a woman like you. They trust her and it rubs off and they think he must be a good man if she’s with him” (p. 154). Do Hélène’s moral boundaries shift when she decides to work with Nathan? How so?

5. Hélène learns early on “the importance of the first few notes” (p. 35) in music, and, by extension, the importance of first impressions in business and otherwise. How does she put that to use throughout her life?

6. Hélène and Nathan visit an Indian agent to buy an Indian transformation mask. Discuss the concept of Nathan as transformer, someone who becomes “something or someone else” (p. 160).

7. Has Hélène learned to be as duplicitous as Nathan?

8. What effect does war have on the characters and how they behave?

9. Hélène refers to “the healing power of money” (p. 161). In what way is that true and in what way has money also corrupted her and Nathan, to greater or lesser extents? How does Hélène and Nathan’s relationship change over time? Do you think Nathan truly loved Hélène? If so, why did he cheat her?

10. Why do you think Hélène let the dogs go after Nathan’s accident?

11. If you ever found yourself in Hélène’s position, what would you have done?

12. Do you agree with the judgment in Hélène’s case? In her own mind, what happened was a terrible act of kindness.

13. Do you consider Hélène powerful and independent in dictating the terms of her own life or is she simply a victim of fate doing the best she can under the circumstances?

14. Discuss the role of duty and honour in the book and how it dictates certain decisions for Hélène and various turns of events.

15. Which era of Hélène’s life did you find you could most relate to and why?

Suggested Reading

The Strange Ways of Inspiration

I was living in Johannesburg when I first learned about pianos. The man I learned from was nearly twice my age; his name was Jacques Franklin. He was from France, via Vietnam and Australia. All of us were from someplace else, via someplace else. There were five or six of us, and we lived in a big brick rooming house on Albemarle Road, with a kindly blue-rinse landlady and a good cook.

Jacques was an itinerant piano tuner; he was often gone for weeks, travelling the countryside in a ten–year old, sand-scoured Volkswagen beetle, searching for pianos that were out of tune. Because of the climate, he told us, many were. His prized possession was a brown leather case with his tuning forks, his wrenches and tweezers, his strips of felt.

It seemed a highly unusual occupation, especially under the circumstances, and so I asked him one day to take me along on one of his swings. I would pay for half the gas and provide an extra water container for the back seat. He agreed, and soon we set off, south into the Karoo, baked earth shimmering like a cool lake in the distance, dust devils and protea shrubs by the roadside. Often the road was just a two-track in the sand; no rain in the area sometimes for months, but every farmhouse we came to had a piano in the parlour. Radio was unreliable, the old vinyls were scratched, and so the piano was both entertainment and civilization. Often they were uprights, sometimes grands: Bechsteins, Broadwoods, Chickerings, Blüthners. And because the pianos were so important, Jacques was always welcome. They asked us in and sat us down and gave us sweet milk tea and cornbread with prickly pear jam, and sometimes if it got too late they gave us dinner and made up rooms for us.

When Jacques went to work in those hot, dry, wall-papered parlours he became a different man from the one I knew from the dining room and the noisy billiard room back on Albemarle Road. He became an old-style family doctor, listening and probing here and there, and within minutes the piano had told him all that was wrong. Pitch, touch, damping, loose bits here and there – whatever the problem, Jacques knew how to fix it. He was the first true master I ever saw at work, and I never forgot it. His instant understanding, his knowledge and his quick hands and his intuition – it was near magic.

At the time I suspected that all these impressions were unique, priceless, really, but I didn’t know what to do with them just yet. So I put them away on the high shelf for another time.

Years later I was working in France, staying at a pension in Nice. There was a Bösendorfer in the music room, and most evenings one of the guests or sometimes the owner’s wife played it. One day a young accordeur came to tune the piano, a woman maybe in her early thirties in a long skirt and her hair piled high. She didn’t use tuning forks, just stood at the keyboard and bent her head to the piano and slowed herself down; I could see that from the other room, that pause, the going inside herself. And then she would touch a key several times and pause and reach to shift the pin, and strike that key again. It took her less than an hour. In the end she sat down and played Chopin, and there was another image of a master for the high shelf.

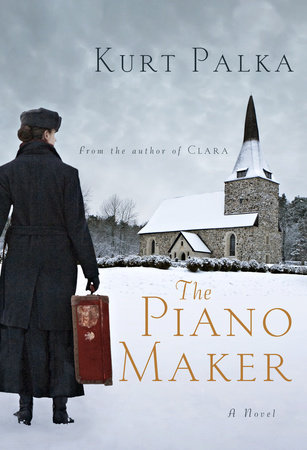

And finally, again years later, I was living in Edmonton, working as a producer and story editor for the CBC, and from there we covered many oil and gas stories in the far north. Minus fifty degrees Celsius at night, ice fog for days, brutal weather. It was there I began to wonder how one might survive an accident in such a wilderness, and from that single thought, from a single haunting image of a horrific mishap that would not leave me, the idea for my new novel The Piano Maker came into being. My research took me back to those early impressions and then to France and to England, and finally to the north shore of Nova Scotia, the French Shore, where it all came together. I drove back to my little farm house outside Mahone Bay, and began to write.

Kurt Palka

2015