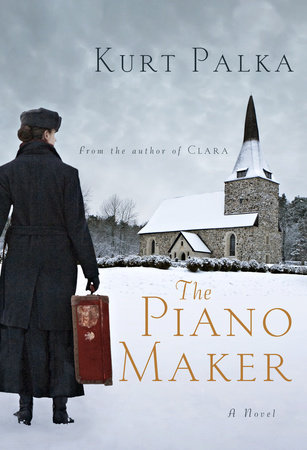

The Piano Maker

By Kurt Palka

By Kurt Palka

The Strange Ways of Inspiration

I was living in Johannesburg as a young man when I first learned about pianos. The man I learned from was twice my age; his name was Jacques Franklin. He was from France, via India and Australia. All of us were from someplace else, via someplace else. There were five or six of us, and we lived in a big old rooming house on Albemarle Road, with a kindly blue-rinse landlady and a good cook. Jacques was an itinerant piano tuner; he was often gone for a week or two, travelling the countryside in a red, ten–year old, sun-bleached Volkswagen beetle searching for pianos that were out of tune. Because of the climate, he told us, many were. His prized possession was a brown leather case with his tuning forks, his wrenches and tweezers, his strips of felt.

It seemed a difficult career, and because I was already interested in people who’d singled out an unusual purpose for themselves and then stuck with it no matter what, I asked him one day to take me along on one of his swings. We drove south into the Karoo: dust devils and protea shrubs by the roadside which was often just a two-track in the sand; no rain sometimes for months, but every farmhouse we came to had a piano in the parlour. Radio was unreliable, the old vinyls were scratched, and so the piano was both entertainment and civilization. Often they were uprights, sometimes grands: Bechsteins, Broadwoods, Chickerings, Blüthners. And because the pianos were so important, Jacques was always welcome. They asked us in and sat us down and gave us sweet milk tea and cornbread with prickly pear jam, and sometimes if it got too late they gave us dinner and made up rooms for us.

When Jacques went to work in those hot, dry, wall-papered parlours he became a different man from the one I knew from the dining room and the noisy billiard room back on Albemarle Road. He became an old-style family doctor, listening and probing here and there, and within minutes the piano had told him all that was wrong. Pitch, touch, damping, loose bits here and there – whatever the problem, Jacques knew how to fix it. He was the first real master I ever saw at work, and I never forgot it. His instant understanding; his knowledge and his quick hands and his intuition – it was near magic.

At the time I already knew that all these impressions were pure gold, but I didn’t know what to do with them just yet. So I put them away on the high shelf for another time.

Years later I was working in France, staying at a pension in Nice. There was a Bösendorfer in the music room, and most evenings one of the guests or sometimes the owner’s wife played it. One day a young accordeur came to tune the piano, a woman maybe in her early thirties. She didn’t use tuning forks, just stood at the keyboard and bent her head to the piano and slowed herself down; I could see that from the other room, that pause, the going-inside-herself. And then she would touch a key several times and pause and reach to shift the pin, and strike that key again. It took her less than an hour. In the end she sat down and played Chopin, and there was another impression of a master for the high shelf.

And finally, again years later, I was living in Edmonton, working as a producer and story editor for the CBC, and from there we covered many oil and gas stories in the far north. Minus forty degrees Celsius at night, ice fog for days, brutal weather. It was there I began to wonder how one might survive an accident in such a wilderness, and from that single thought, from a single haunting image, my novel The Piano Maker took off. Research took me back to France and to England, and finally to the north shore of Nova Scotia, the French Shore, where it all came together. I drove back to my little farm house outside Mahone Bay, and began to write.

Kurt Palka

March 2015

Author

Kurt Palka

The Autumn of Madame Hélène is Kurt Palka’s ninth novel, following the bestsellers The Piano Maker, Clara, shortlisted for the Hammett Prize, The Hour of the Fox, and The Orphan Girl. His work has been published throughout the Commonwealth, and in nine countries in Europe and Asia.

Learn More about Kurt Palka