Author Q&A

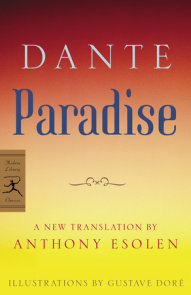

Conversation with ANTHONY ESOLEN, translator of Dante’s INFERNO

1. What attracted you to Dante’s work?

Dante is arguably the greatest poet who ever lived; I think only Homer and Shakespeare deserve mention in the same breath. It is hard to find a poet whose art is as severe, as precisely chiseled, and as intellectually well-defined as is Dante’s, yet at the same time his art possesses a kaleidoscopic complexity that staggers the imagination. Each of these qualities is rare enough. To find them at once in the same author, writing an epic about the ultimate questions, is–well, all I can say is that we will not see his like again.

2. What made you interested in doing translations?

Once, when I was a graduate student attending a party given by a professor of German, I met a young man who said he was studying Georgian, the language spoken by the natives of the Caucasus mountains. "Why on earth would you do that?" I asked, thinking I’d come upon another harmless academic snob. His answer shamed me. "One of the greatest living poets in the world lives in Georgia. He writes epics in Georgian, and I want to translate them into English so that other people can read them." Of all the things that academics do–some good, some bad, many simply vain and useless–I could hardly think of anything of greater value than to devote your talent to so humbling a task. Then, years later, my wife Debra suggested the same thing to me, and that is when I started work on Lucretius.

3. Is Dante difficult to render well in English? What were some of the challenges you faced as a translator, and what are you trying to achieve with this translation?

Dante is difficult, period. I think, though, that once you get over the issue of rhymes, English is actually a pretty good language into which to translate the Commedia. (I love German, but I do shudder to think of Hell in the Teutonic tongue!) English is a peculiar language, after all: it contains its good stock of short, brusque, German or Middle French words, enriched by an enormous stock of words derived directly from Latin or from the Romance languages. So the vocabulary, with all its subtle semantic and tonal shades, helps a lot, as does that most supple tool, English iambic pentameter.

What was I trying to achieve? I want to make people fall in love with Dante–really fall in love with him, and not just pretend to in order to score points at a literary soiree. For that, you need swift and vigorous but also musical verse. And I’m hoping that that’s what I’ve provided.

4. Why iambic pentameter?

Nothing else will do. Free verse won’t do; non-metrical (that is to say, free but not too free) verse won’t do, either. Music must somehow be translated into what retains traces of the music. Iambic pentameter is the natural meter of English narrative poetry, imitating most faithfully the rhythms of our speech, and it is capable of extraordinary variation (consider the uses to which Shakespeare put it in his plays). We are fortunate to have it.

5. What kind of research did you do for this translation, and how did you go about doing it?

For the translation, I consulted many Italian editions of Dante, especially those whose notes brought out most clearly the meanings of his coinages or of strange dialectal words. As for the rest of the book, let’s just say that for a year I had twenty volumes of Aquinas cluttering up the office.

6. Why has the INFERNO been so influential and admired over the ages and in our own time?

Well, for a while Dante did go out of fashion: too medieval, you know. With the important exceptions of Milton and Blake, he really did not have many admirers among English writers from the Tudors to the end of the eighteenth century. The English Romantics and their Victorian followers rediscovered his greatness–or at least they found the story of Dante and Beatrice to harmonize with their own beautiful, dreamy, half-sickly love of the chivalric past. That was in England; in Italy, Dante has been the poet who defined both language and nationhood. But I think that modern readers are attracted to Dante because they find in him what the modern world cannot offer: a cogent and coherent vision of the universe.

7. Why, in this new translation, did you include the “sourcebook” that presents Dante’s most important religious sources?

I’m a professor by trade and know what sorts of ancillary material I would want, and have wanted, in books I assign the students to read. Also, I think that you miss much of the joy of a work of art when you cannot walk a little way into the world that gave it birth.

8. What do you want readers to take away from this new translation?

A love for Dante, and maybe a clearer view of that great peak of intellectual and artistic achievement: the Middle Ages.

9. What are you working on now?

Don’t tell my editor, but I’m taking a break! Actually, I’m going to be writing the introduction and the notes to my translation of Paradiso, while revising the completed translation. Purgatorio is finished and ready to be printed.

10. What other languages do you speak fluently and/or translate?

How fluently I speak it, I’d best let the natives judge, but I do speak German too, and read French, Anglo-Saxon, Latin, and some (New Testament, which is the easy stuff) Greek. I’ve translated Lucretius (De Rerum Natura; Latin) and Torquato Tasso (Gerusalemme Liberata; Italian), and one of these days I’m going to make good on a threat to translate into English verse a passel of Anglo-Saxon poems not named "Beowulf".