READERS GUIDE

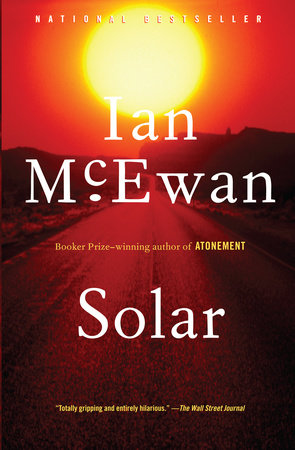

The introduction, discussion questions, and suggested further reading that follow are designed to enhance your group’s discussion of Solar, the new novel by Ian McEwan, Booker Prize winner and bestselling author of Amsterdam and Atonement.Introduction

Solar approaches the largest and most important of themes—global warming—through the very particular lens of Michael Beard, a disheveled physicist floundering in the aftermath of a career that had brought him the Nobel Prize many years before.As the novel begins, Beard’s fifth marriage is unraveling. But this time, in a reversal of roles, it is because his wife is having an affair. Infidelities are Beard’s stock-in-trade, but being cuckolded is a new and unsettling experience for him, and it seems part of larger downward trend in his life. He still speaks at conferences, lends his name to scientific institutions, and leads a government program devoted to developing clean energy. But he does all these things in a halfhearted way and is largely indifferent to the problem of global warming. That all changes when Aldous—an earnest postdoc who is passionate about both climate change and Beard’s wife—enters the picture. After a freak accident, Beard is left with Aldous’s ingenious plans for creating solar energy by imitating the process of photosynthesis. He sees a chance to reestablish his prominence as a physicist and save the world while he’s at it.

But Michael Beard is an unlikely savior. His personal life seems to reflect not the solution to the problem of global warming but the cause of it. He is a man of immoderate appetites—for women, for acclaim, and, most irresistibly, for crisps. Dangerously overweight, he still cannot control his desire for fattening foods or alcohol. He vows to go on a diet, again and again, and repeatedly he fails. He is, like the species to which he belongs, an expert rationalizer and a skilled avoider of unpleasant facts. There is a blotch on the back of his hand that is ominously growing and darkening, and yet Beard, even though he is a scientist, cannot bring himself to take the proper medical action. He hesitates while the melanoma grows and threatens to metastasize. His doctor tells him that not thinking about the blotch won’t make it go away—a warning that could just as accurately be directed to those who prefer not to think about global warming. In short, Beard embodies many of the characteristics of a civilization addicted to comfort and unable to change its course even as it is heading toward the cliff. That Beard sees himself as the man to create a way of harnessing solar energy sufficient to halt the climate catastrophe adds a layer of irony to the story that strikes at the heart of the human predicament. Beard is himself symptomatic of the narrow self-interest that keeps human beings from putting the health of the planet above their own desires.

The remarkable achievement is that McEwan manages to make Beard such a sympathetic character—though at times he comes closer to being pathetic than sympathetic. We watch with a kind of fascinated uneasiness as his self-created disasters threaten to pull him under, and yet with a kind of admiration and good humor, too. Perhaps because he is, in both his weaknesses and strengths, so much like us.

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. Beard loves physics in part because he believes that it is “free of human taint” (p. 10). In what ways does the novel complicate this belief? In what sense is Beard’s own work “tainted” by human entanglements?

2. The narrative structure of Solar is mostly chronological. What effects does McEwan achieve by occasionally departing from a straightforward chronological progression?

3. Beard claims he does not believe in the possibility of “profound inner change” (p. 77). Does he remain unchanged over the course of the novel?

4. How does McEwan manage to make Beard such a sympathetic character despite his many foibles? What are his most salient character flaws?

5. Why is Beard so attached to preserving what he calls his “unshareable core”? (p. 307). Why does he find it impossible to tell Melissa that he loves her? Why do his marriages keep falling apart?

6. In what ways is Solar a satirical novel? What are its main satirical targets? How, for example, do postmodernists come off in the book?

7. What are some of the funniest moments in Solar? How does McEwan create such brilliant comedic effects?

8. Look at the encounters between art and science in the novel, those occasions when Beard squares off with people from the humanities—novelists, folklorists, postmodern feminists, etc. Who gets the better of these confrontations? Is the book as a whole making a point through its depiction of these encounters?

9. What is the significance of the entropy in the boot room on board the ship that is holding the conference on climate change? What does this chaos and carelessness suggest about humanity’s ability to stop global warming?

10. Beard has a remarkably clear conscience; he is largely untroubled by his affairs and deceits, his theft of Aldous’s ideas, his framing of Tarpin, etc. Why is he so free of the guilt that might afflict most other men?

11. Several times during the course of the novel it appears that public infamy—born of journalists’ insatiable desire for controversy and Beard’s own willingness to step into it—will doom Beard’s career. What enables him to emerge from these disasters relatively unscathed? Will he be as lucky getting out of the mess he’s created at the very end of the book?

12. How surprising is the ending of the novel, particularly the final sentence? What is the swelling sensation that Beard feels in his heart as his daughter approaches him? What is likely to happen to Beard next?

13. How does the appendix containing the presentation speech for Beard’s Nobel Prize alter the way Beard is finally viewed? Why would McEwan choose to attach this appendix to the body of the novel?

14. Solar is in many ways a picaresque and at times farcical novel, and yet it also engages a theme of major importance—global warming. What is the connection between personal and planetary catastrophe in the novel, between the meltdown of Beard’s personal and professional life and the kind of greed, dishonesty, rationalization, and failure to face facts that has resulted in the climate crisis? What is the significance, in this context, of Beard’s inability to moderate his eating habits and his sexual pursuits?

15. What does Solar contribute to our understanding of climate change?

(For a complete list of available reading group guides, and to sign up for the Reading Group Center e-newsletter, visit www.readinggroupcenter.com.)