Author Q&A

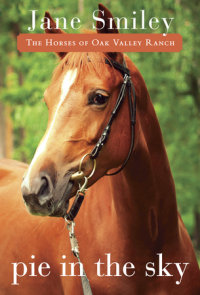

A Conversation with Jane Smiley(From Publishers Weekly’s “Children’s Bookshelf,” 8/13/09)By Joy Bean You obviously love horses. Is this the kind of book that you would have liked to have read as a child?

JS: Well, it’s more or less the kind of book I did read. When I was a child in 1960 – I was 10 and 11 that year – there were plenty of horse book series. I loved them all and read them all. I read the Black Stallion series, and other Walter Farley books. There were others more geared to girls, like Silver Birch, about a troop of Girl Scouts in Wisconsin. I ate them up. I also read Nancy Drew and other series. That was what kids’ literature was back then.

Did you have or ride horses while growing up?

JS: When I was really little in suburban St. Louis, there was a pony riding area. The people there would stick me on a pony and make it move. I started doing that when I was five and then after that I made my mom take me to a particular stable and we would ride there. When I was 11, I started taking lessons. I was always doing something horsey.

What made you want to write for a younger audience?

JS: My editor, Joan Slattery, pointed out to me that there were no horse books for girls anymore. As soon as she said it, it opened up this whole world to me. It was time to return to my roots.

I thought of the fact that where I live in California, it is the center of a different type of horse training that is going on. I had recently seen the film My Friend Flicka, in which they break the horse the old-fashioned way. They wear the horse down until it can’t fight anymore. They consider the horse “broke” then. But where I live, it is the center of a different kind of training that was started by two men, Bill and Tom Dorrance. Starting in the 1960s, they were observing horses and they saw how they relate to one another. They inferred what the horse’s body language was saying to each other. They are hierarchical and they saw how one might bring himself to be the boss of the group. The two of them, especially Tom, took these lessons they learned from horses and applied it to horse training.

This type of training, the encouraging of horses to cooperate, hasn’t been portrayed in a book for girls before. I also read a wonderful book about the domestication of animals called The Covenant of the Wild by Stephen Budiansky and the author talks about how domesticated animals retain their play instincts. You can train them to do a job that’s fun, not just do a job. Horses will jump jumps because it’s play for them.

The character of Jem Jarrow is based on Tom Dorrance. I met him once. He was a small, modest guy who was a genius with horses.

Abby has to deal with a strong-willed father as well as a strong-willed horse. Did you set out to write the book with these two relationships changing side-by-side throughout the novel?

The book is part of a series of three or more books. The horses come and go and it just happened that I wanted to talk about the Tom Dorrance way of training in the first book. I wanted to talk about the contrast between the old way of training and the new way. I’ve already written volume two and working on volume three now. Other aspects of Abby’s life are in future books. A new trainer comes in. Abby has to learn how to jump, but I did want to get Jem Jarrow in there so that his ideas could influence the way the readers would see horses.

Abby has a tense relationship with her father. She continually stands up for herself, even though she is scared to do so. The father seems to be a little more lenient with Abby than he was with her older brother. Is that because she is a daughter, or because she has proved herself as being smart and level-headed with the horses?

It’s because she’s the daughter. The father relies on Abby to get the job done and she does get the job done. When challenged by his son, the father isn’t able to handle it. At some point in the book, I mention that the son and father get along, that they’re cut from the same cloth. Then it’s no surprise that when the son decides to be his own boss, the father can’t handle it. All those men—the father, the son, the uncle who comes to visit—their relationship is uneasy. With all of them, no one is going to be told what to do. We all know families like that, where the girls get a pass.

You add a lot of horse care information into the book, without it reading like a how-to book. Was this intentional? Did you want readers to come away from the book knowing about the dynamics between a horse and a person?

JS: One of the things that the father and Uncle Luke epitomized was that a horse was mechanical. If you said back in the 1960s that a horse had thoughts or could be like a person, people would just laugh at you. When I was a child, my parents bought me the World Book Encyclopedia set. The article on the horse had a chart of animal intelligence, and horses’ intelligence was on the bottom and I really resented that. Pigs were at the top. My experience with horses is that they’re really smart and they’re thinking all the time. What I want to do throughout the whole series was to have Abby see the horses as individuals and not machines and that the world they live in is interesting and the way they see the world is interesting.

Did you know all of the horse information you wrote about from your experience with horses, or did you have to do research for the book?

JS: I knew most of it because I’ve been working with trainers for 15 years or so. Since I moved to California in 1996, I’ve had these trainers that were trained by Tom Dorrance himself. In writing the book, I asked them to do what Tom would have done. They were able to help me by telling me certain lessons I should write about.

I found it impressive that Abby has a lot of work to do every day and she seems to do her work without any fuss.

JS: She does! I set the book in the 1960s because things have changed a bit. I don’t know if a child today would do so much work. Maybe they would, but I felt like this was normal for a child back then. I don’t think living on ranches is so much a part of our world anymore and that’s why I set it in the 1960s.

Have you ever had a horse like Ornery George? How did you deal with him?

JS: Yes, and I did not deal with it very well. I had made quite a sophisticated analysis of him, but that didn’t protect me from being dumped by him. I worked with him for four years. It was like living with a man who had an abusive childhood. He loves you and was attentive to you, but there is always the moment when he could betray you because he has to protect himself. A horse can have a bad childhood, but fortunately their childhoods are much shorter than ours.

Do you plan on writing any more books for younger readers? Any ideas about what you might like to write about?

JS: This series has got my interest now, so I’m not really thinking of that. But I did try to sell a book to my editor about yawning, and it would put kids to sleep all over the world. She thought it was boring.