Best Seller

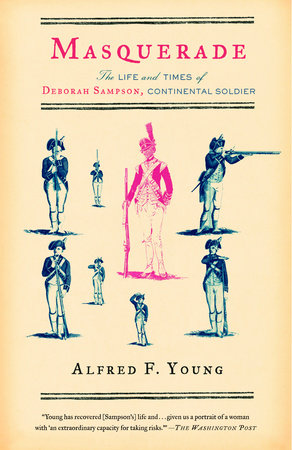

Masquerade

Paperback

$22.00

Published on Mar 08, 2005 | 432 Pages

Author

Alfred F. Young

Alfred F. Young was professor emeritus of history at Northern Illinois University and was a senior research fellow at the Newberry Library in Chicago. He lives in Durham, North Carolina. He passed away in 2012.

Learn More about Alfred F. Young