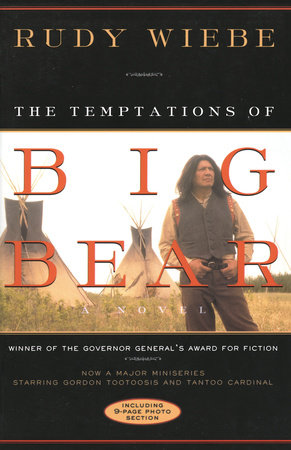

Temptations Of Big Bear

By Rudy Wiebe

Early in his writing career, Rudy Wiebe’s imagination was caught by a heroic character of Cree and Ojibwa ancestry whose birthplace was within twenty-five miles of where Wiebe himself was born 110 years later. The man’s name translated into English was Big Bear, and he came to be the subject of one of Wiebe’s most highly praised works of fiction. A modern classic, Wiebe’s fourth novel is a moving epic of the tumultuous history of the Canadian West. The book won the 1973 Governor General’s Award, and in the 1990s was made into a CBC television miniseries based on a script co-written by Wiebe and Métis director Gil Cardinal, shot in Saskatchewan’s Qu’Appelle Valley.

From the early days of North America, European settlers forced Natives aside, taking over their land on which they had lived for thousands of years. Big Bear envisioned a Northwest in which all peoples lived together peaceably, and in the 1880s made history by standing his ground to keep his Plains Cree nation from being forced onto reserves. The buffalo food supply was vanishing, but Big Bear led his people across the prairie, resisting pressure to cede rights to the land and give up freedom in exchange for temporary nourishment. The struggle brought starvation to his followers, tearing apart the community and eventually his own family. The story follows Big Bear’s life as he lives through the last buffalo hunt, the coming of the railway, the pacification of the Native tribes, and his own imprisonment.

Wiebe’s magnificent interpretation of Western Canadian history encompasses not only his hero’s struggle for integrity and justice but also the whole richness of the Plains culture.

Author

Rudy Wiebe

Rudy Wiebe was born on October 4, 1934, in an isolated farm community of about 250 people in a rugged but lovely region near Fairholme, Saskatchewan. His parents had escaped Soviet Russia with five children in 1930, part of the last generation of homesteaders to settle the Canadian West, and part of a Mennonite history of displacement and emigration through Europe and Asia to North and South America since the seventeenth century. In 1947 his family gave up their bush farm and moved to Coaldale, Alberta, a town east of Lethbridge peopled largely by Ukrainians, Mennonites, Mormons, and Central Europeans, as well as Japanese, who ended up there during WW II.Rudy Wiebe read as much as possible from an early age; his first reading materials were the Bible, the Eaton’s catalogue and the Free Press Weekly Prairie Farmer; he also recalls listening to his parents’ stories of Russia. By Grade 4, he had read through the two shelves of books available in the one-room schoolhouse. Growing up, he enjoyed Les Miserables, Toilers of the Sea, David Copperfield, Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Greek myths and Norse legends. Later an admirer of Faulkner, Márquez, Borges and Tolstoy, Wiebe has always held to the fundamentals of plot, character and, above all, story. He believes stories should begin in the specific and local but expand into “a human truth larger than any individual.”Wiebe won his first prize for fiction while studying literature at the University of Alberta, where he enrolled in a writing class and began producing poems, plays and stories. His winning story in a Canada-wide contest recounted a young boy’s response to the death of his sister – based on Wiebe’s own experience – and was published in the magazine Liberty in 1956. After earning his B.A., Wiebe left for the ancient University of Tübingen in West Germany on a Rotary Fellowship to study literature and theology, an experience that increased his respect for older and richer communities. Tena Isaak of British Columbia joined him there and they were married. The couple travelled in England, Austria, Switzerland and Italy before returning to Edmonton, where Wiebe completed his M.A. in creative writing. His thesis grew into his first novel, Peace Shall Destroy Many. In 1962 Wiebe earned a Bachelor of Theology degree from the Mennonite Brethren Bible College; he considered becoming a minister. He was editor of Winnipeg’s Mennonite Brethren Herald when Peace Shall Destroy Many was published. Many conservative ministers and Mennonites in small towns objected to the novel’s frank and at times unflattering portrait of community life, and there was considerable opposition to the book. “I wasn’t exactly sacked as editor . . . but the committee came to me and said ‘Ahem.’ I resigned.” The strength of this reaction made him think hard about the power of the written word, and reinforced his sense of wanting to be a writer.Wiebe then was invited to teach at a Mennonite college in Goshen, an agricultural town in Indiana with a large Mennonite and Amish population, where he would be Assistant Professor of English from 1963 to 1967. Goshen College was a lively and stimulating intellectual community where Wiebe committed himself to writing, study, teaching and travel. “I encountered men and women of real perception . . . really literate Christians who saw themselves as Jesus’s followers and at the same time were acquainted with the thoughts of others and had brought that kind of understanding to bear on what it means to be a Christian. The best thing that ever happened to me was the meetings we had every two or three weeks in one home or another – seven or eight of us, a psychiatrist, a couple of theologians, a couple of literary people. There were the best theologians there, I think, the Mennonite Church has ever had.” Wiebe published his second novel, First and Vital Candle, and began to explore the western United States and the Mennonite settlements in Paraguay. He returned to Edmonton as a professor in creative writing and English at the University of Alberta, and immersed himself in Canadian literature. He wrote reviews, essays and articles, edited anthologies and was soon established as a major figure in Canadian letters. In 1973, his novel The Temptations of Big Bear won a Governor General’s Award. Since then he has continued to win the highest praise for his books of fiction and non-fiction. He has written numerous film and television scripts, lectured internationally from Denmark to India, and given readings from Adelaide to Puerto Rico to Helsinki and Igloolik. For thirty years he taught literature and creative writing at colleges and universities in Canada, the United States and Germany. Now retired from teaching, his former students include such accomplished writers as Myrna Kostash, Aritha van Herk, Thomas Wharton and Katherine Govier. Wiebe was called the first major Mennonite writer to place his community’s experience in a broader framework. Mennonites assert the fundamental authority of Scripture, especially the New Testament, as a practical guide to life. But while Wiebe imbues his work with a deep moral seriousness, his focus has always been on narrative. “I never consciously think of writing a so-called Christian novel. I don’t think Albert Camus ever thought of writing an existentialist novel, either. I think of getting at, of building, a story.” As a prairie writer, he has often concerned himself with Native stories, feeling place of birth to be more important than blood ancestry. “Those Mennonite villages in Russia are my heritage, but not my world. The world I feel and sense in my bones is the bush of northern Saskatchewan, of prairie Canada.” Native spirituality, with its vital links to the physical world, has always attracted him. But his fiction manages to transcend nationality and locale to explore the struggles of communities and individuals; his books and stories have been translated into nine European languages, as well as Chinese, Japanese and Hindi.Whatever Wiebe’s focus in a given work, he has always chosen ambitious themes, and his work rewards readers with an intensity seldom rivalled. He is a voice of Canadian fiction that cannot be ignored, and whose work promises to endure.

Learn More about Rudy Wiebe