READERS GUIDE

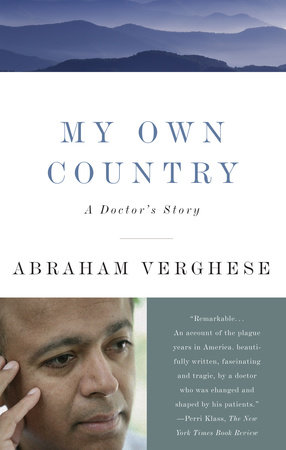

The questions, discussion topics, and author biography that follow are intended to enhance your group’s reading of Abraham Verghese’s My Own Country. We hope they will enrich your understanding of a book that is rich in themes for stimulating group discussion.Introduction

In My Own Country, Abraham Verghese, a young Indian doctor born and educated in Ethiopia, tells of the four years he spent in a Tennessee town as a specialist in infectious diseases. His story begins in 1985, when he arrives in Johnson City, Tennessee, a quiet town in a mountainous region. At that time, Johnson City’s inhabitants had heard about AIDS, but saw it purely as a big-city problem, and had no idea that the disease could invade their own community, a "typical" Southern town with little experience of illegal intravenous drug use or overt homosexuality. But no community, as this book eloquently demonstrates, is immune to AIDS, and the disease had already made its way to Johnson City, silently infecting a number of people. By 1989, Verghese was caring for more than eighty HIV-positive patients; unlike most specialists, who focused only upon their areas of expertise, he was the patients’ primary care provider. And because the nature of the illness forces the doctor to confront and deal with intimate, private issues, Verghese found himself becoming intensely involved with the unique personal story of each patient’s life. Verghese shows us the patients’ struggle to deal with their illness, and vividly shows how their loved ones cared for them, even as both the patients and their families had to deal with societal prejudice. While some patients gave in to the disease, many found that being diagnosed as HIV-positive was not the end of their lives but the beginning of a new existence which, because of its precariousness, was more intense and far more precious.Caught up in these dramas, Verghese found himself drifting dangerously away from his wife, who was fearful of AIDS and felt shut out by her husband’s preoccupation with his patients’ lives. Verghese’s attempts to save his marriage and his simultaneous search for a home, for his "own country," finally lead him away from the Tennessee he has grown to love, and where he had hoped after years of wandering to put down roots at last. But though Verghese must move on, in a spiritual sense he does find his "own country"–in his vocation as a healer. My Own Country, while it incorporates the stories of many patients, is primarily the story of a doctor and his very personal journey.

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. Verghese describes the early eighties, before AIDS had spun out of control, as "a time of unreal and unparalleled confidence, bordering on conceit, in the Western medical world," [p. 24] in which doctors felt they had achieved "mastery over the human body"

[p. 25]. How does the reality of AIDS undermine this ultra-modern, technological ideal of medicine? How does Verghese’s idea of the doctor’s role change during the course of the narrative? Do you believe that his turning back toward the older ideal of treating the whole patient, body and soul, might be a harbinger of a general medical trend?

2. When Verghese arrives in Johnson City, he says, "I knew no openly gay men. I only knew the stereotype" [p. 23]. What changes does his attitude toward homosexual men undergo during his years at the Miracle Center? How does Verghese’s initial perception of himself as an outsider in Johnson City make him especially sensitive to his patients’ problems with their families and community?

3. Johnson City in the mid-eighties is "a place where Jerry Falwell’s pronouncement that homosexuals would ‘one day be utterly annihilated and there will be a celebration in heaven’ was taken as a self-evident truth" [p. 56]. Yet when AIDS strikes people they love, many inhabitants of Johnson City prove remarkably supportive. How does their personal contact with the disease work to falsify the "gay" stereotype they previously held? Does Verghese, simultaneously, succeed in breaking stereotypes about "Falwell country" that readers themselves might hold? What other stereotypes does Verghese undermine in his story?

4. Verghese’s story indicates that to feel part of a group is vital to human survival and well-being. How do the various groups Verghese describes–the gay community, the TAP support group, the church, the medical fraternity, the expatriate Indian community–nourish and strengthen their members? Are they always nurturing, or do they also put up barriers between their members and the outside world? Is Verghese himself fully a member of, fully at home in, any of these groups?

5. How do the different members of Gordon’s family react to his homosexuality and illness? How does each, in his or her different way, cope with Gordon’s condition? In what way does Gordon typify the "generation of young men, raised to self-hatred" and their collective "voyage, the breakaway, the attempt to create places where they could live with pride" [pp. 402-403]?

6. "I heard different but strangely similar versions of this story from families of gay men: There was always the God-given talent that accompanied their God-given sexuality, always the special creativity and humor" [p. 92]. Verghese speculates on two possibilities: these qualities might be as biologically determined as sexuality, or they might be developed to compensate for the men’s essential difference. What do you think of these ideas?

7. What is Verghese’s reaction to Gordon’s and Will’s visions of Jesus? How does religion affect the way these patients deal with their disease? Does it help them to fight? Does it help them to come to terms with defeat? Does it ever hinder them from facing their problems truthfully?

8. Verghese comes to see AIDS "as the litmus test for nurses and physicians, a means of identifying who would and who wouldn’t" [p. 105] provide treatment and, in so doing, risk their own health. Is there an excuse for the hostile attitude of nurses who don’t want to treat AIDS patients? Should people who have committed themselves to careers as doctors or nurses be morally obligated to treat any and every patient? In Johnson City, just how deeply does the hospital staff’s attitude towards AIDS change over the course of the four years Verghese describes?

9. When Ethan Nidiffer explains why he didn’t alert his dentist to the fact that he was HIV-positive, Verghese admits that he "could certainly see his point of view" [p. 306]. What is your point of view on this issue? How much responsibility lies with the patient, and how much with the dentist? Should patients always be obliged to inform their doctors that they are HIV-positive, even if that means they may not find treatment?

10. How do Gordon, Fred, Ethan, and Raleigh differ in their visions of themselves as gay men and as part of a larger gay community? Can you see any parallels with Verghese and his own search for a community, a home?

11. Will and Bess Johnson see themselves as "innocent victims" of the disease–as opposed, by implication, to the gay men who also suffer from it. How might you explain Verghese’s complex reaction to this notion? Do the Johnsons strike you as essentially more "innocent" than the gay men in the narrative? This issue relates to the way the cancer patients at the VA hospital are perceived as dying with honor, while so many HIV patients harbor feelings of shame. How are the concepts of honor and shame, innocence and guilt, addressed by the TAP members? By the Johnsons? By Rajani? By Verghese himself? Do these attitudes reflect those of the larger American culture?

12. Do you agree with Bess and Will’s decision that secrecy about their HIV infection was vital? Why were they so overwhelmingly concerned with secrecy? What makes them able to draw comfort from their church even while assuming that their fellow church-goers would not stand by them in their illness? Do you blame Bess and Will for not speaking out and trying to help others who suffer from the disease, or do you think that they had every right to their privacy?

13. Because of his work, Verghese comes to believe that "our moments of true safety are rare." Is such a knowledge a handicap, or can it bring increased strength? How does the enormous change in Vickie McCray’s life and character relate to this knowledge?

14. Do you believe that the situation Verghese describes in Johnson City accurately represents the situation for AIDS sufferers in the United States as a whole? If you have any experience with the disease, do you find that patients feel isolated, feel the need to keep their condition a secret? In your own community, does compassion outweigh prejudice? Are there adequate support resources for the HIV-positive? How do different members of the local and national government treat this volatile issue?

15. At the end of the book, Verghese states that AIDS work will always be his vocation. How does Verghese’s powerful sense of mission and his unselfish giving of himself affect his family life? Is the sort of schedule he has undertaken necessarily incompatible with a full family life? How might a busy doctor’s wife and children share in his professional life?

16. When Verghese arrives in Johnson City, he feels he has found a home, his "own country" [p. 46]. Does he still see it in this way at the end of the book? If so, why does he leave? How does the Malcolm Cowley poem placed at the beginning of the narrative apply to Verghese’s personal quest?

About this Author

Abraham Verghese was born in Ethiopia in 1955, of Southern Indian, Christian, parents. He attended medical school in Ethiopia, worked as an orderly in various hospitals in the United States, then went to India to complete his medical education. In 1980, he returned to America. He did his internship and residency in Johnson City, Tennessee, went to Boston to train as a specialist in infectious diseases, and returned to Johnson City to practice his specialty. It was there that he unexpectedly found himself dealing more and more, finally almost exclusively, with HIV and AIDS, which soon became his metier, the focus of his career. He spent four years in Johnson City, 1985 through 1989, becoming an expert on the disease.In 1990, Verghese moved to Iowa, where he worked at the University of Iowa outpatient AIDS clinic. He also attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and while there he was encouraged to turn his Johnson City experiences into a book. Verghese is now Professor of Medicine and Chief of Infectious Diseases at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center in El Paso, Texas.

My Own Country is Verghese’s first full-length book. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, The North American Review, Sports Illustrated, Story, and many medical journals.