READERS GUIDE

Introduction

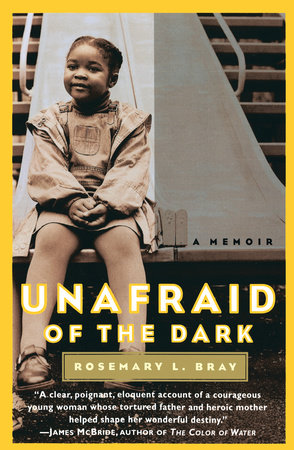

How much hardship can you heap on a child before she gives up? Reading Rosemary Bray’s memoir, Unafraid of the Dark, you might be tempted to answer: however much you do, she simply won’t.The bigger answer, the one that can be applied to most people, is that the human spirit can survive deprivation in many forms as long as it’s sustained in other important ways. Perhaps, as in Bray’s case, by a mother and father who believe fiercely in the value of education. Or by libraries where books are free to all who choose to visit. Or by a teacher, maybe just one in twelve or sixteen years of schooling, who looks at a student and says, you’re special. Or by welfare payments that may cover only the bare minimum of rent and utilities, but allow a mother to stay home, close to her children, while she scrimps, scrambles, and saves for all the other things the family needs to survive.

Bray’s mother was such a welfare recipient in Chicago in the 1960s. She raised Bray and her brothers and sister in an apartment that was too small and too cold, but her ADC payments allowed her to stay home and raise them. To walk them to school in the morning and pick them up in the afternoon. To put them to work beside her on Saturday mornings to keep the apartment spotless and smelling of bleach, and then herd them to the library as a reward for work well done. To use a portion of those welfare payments for Catholic school tuition because the Chicago public schools were not doing the job they needed to do–educating all children, black and white.

But those same welfare payments forced Bray’s father to become one of a legion of “shadow men” who left through the back door as the ADC caseworker walked in the front door, since the state “frowned on the presence of men” in homes receiving welfare payments. A complicated man, a “relentless worker who gambled, not a gambler who occasionally worked,” Bray’s father alternately beat his wife and children and encouraged his daughter to study harder, do better, and make something of herself in a white man’s world. She did.

Bray graduated from Yale. She became an editor at a national magazine, Essence, before she turned twenty-five. She was an editor at The New York Times Book Review. She overcame her wariness of men and marriage and mothering to create a loving partnership with her husband and create a family too, raising her young boys with the same sense of security, warmth, love, and high expectations her mother gave her, and without the fear and anger that her father and poverty added to the mix.

Bray’s story is an inside look at how the welfare system, for all of its serious flaws, helped raise families up by guaranteeing them some basic support. And it is a warning of the damage we’ve done by dismantling that system in such a sweeping motion.

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. The author writes, "My mother’s endurance was a mystery to me….[W]hat I never understood was how she was able to do what she did for as long as she did it." (p. 10) In what ways does she have a better understanding of her mother’s endurance by the end of the memoir?

2. Talk about the author’s point that one of the basic flaws in ADC was that it wasn’t designed originally as a permanent social insurance program like Social Security. Do you agree or disagree? And why?

3. The author notes that her mother and other African-American women of that generation felt their lives were less important than the lives of the children they raised. Is this a truth that still exists today? That transcends economic and racial barriers?

4. The author’s father beat her and terrorized her family. He also encouraged, demanded, and instilled a love and respect for books and learning. If the reverse were true (a loving father who had no respect for learning) how might her life have been different? Do you think she would have accomplished what she has?

5. Welfare made the author’s father a "shadow man." Talk about this phenomenon and what it does to men and to their families.

6. Talk about the changes that occur in the author’s perceptions and understanding of her home and neighborhood every time she ventures farther from it.

7. Is the author more like her father than not? In what ways?

8. How can a teacher change a student’s life? How did her teacher at Francis W. Parker School do that for the author? Talk about experiences you’ve had with an inspirational teacher.

9. Talk about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.–the author’s perceptions of him and her understanding of the movement for racial equality and how it changed at different points in her life. Can you chart such points in your life?

10. The author writes that she learned to "negotiate a way of belonging in this largely white, culturally very different world without abandoning the rest of my real life." (p. 106) What price does she pay for doing this? Is there a choice for African-Americans? Do white people ever have to do the same?

11. Diversity and integration? Or, separatism and co-existence? At what points in the book does the author feel one way or the other is best?

12. Talk about the author’s pragmatism regarding affirmative action. Talk about the current state of affirmative action–the arguments for and against it.

13. When the author enters the workforce, she has to deal with a whole new breed of problem–an unsupportive boss. Talk about this as a reality of life. Is it worse, or more common, for African-Americans?

14. Free of her husband, her children grown, the author’s mother chooses to be a companion and helper to a wealthy white woman. How does the author come to terms with this? How would you?

15. Talk about the author’s relationship with Royce in Harlem. Would you have helped in the same way?

16. Talk about the difference between the world of men and the world of women. In the African-American community, who pays a bigger price for day-to-day existence? For achieving dreams?

17. Talk about Evangelical Christianity as a faith that leads Christians "not to a larger embrace of the world…but to a profound sense of hopelessness…. Their great love of God had ruined them in the company of humanity." (p. 262)

18. The author considers "color-blindness in America both an insult and a lie." (p. 263) Do you agree? Why or why not?

19. The author notes that Shelby Steele argues for forgetting and forgiveness in regard to racial issues. The author argues that "consciousness is the only path to forgiveness and reconciliation." (p. 268) What do you think?

20. Talk about the welfare reform bill of 1996. Do you agree with the author that it is a "betrayal of our interests as women." (p. 274) Have your feelings about this been influenced by reading this memoir or from your personal experience with welfare?