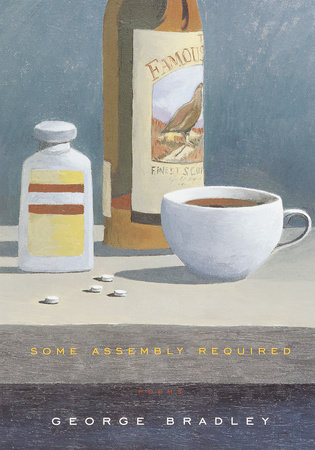

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Alfred A. Knopf staff and George Bradley

AAK:Please explain the title of this new collection?

GB:It was a title that was arrived at out of expedience: the book previously carried the title "For the New Ark", which drew mostly puzzled stares and long silences in reaction. My editor, Deb Garrison, suggested the current title, which is taken from a poem in the book. The poem is written in two parts, alternating on the page and requiring the reader to assemble the whole; as a title for the book, the implication is that the purchaser of the package will have to do some work; the reader is expected to do his part.

AAK:How is this collection different from your others?

GB:I don’t know that it is much different, except that it necessarily reflects what has happened to me over the past five years. No breakthroughs, no grand artistic advances, no new visions. Just a process of continuing into middle age, what with people dying around one and the human responsibilities piling up. Whether I like it or not, it is more mature.

AAK:Why did you choose to focus on topical subjects such as the environment and the media?

GB:I didn’t, really. Only some of my poems are entirely connected to the immediate world in that way. The others use the immediate world as a place to start from, as a springboard. Of course, that doesn’t mean that one can get along without reality. You have to start somewhere. As Wallace Stevens puts it: "The real is only the base, but it is the base."

AAK:In poems such as "A Poet in the Kitchen", you seem to reflect on your own life. Does this poem have autobiographical elements?

GB:Yes, the poem has autobiographical elements, as do most of my poems. But it is the poem that counts, not the autobiography, and as a result the poet will always tailor the autobiographical elements to fit a notion of art. To take the poem you ask about, "A Poet in the Kitchen," the apartment as described is indeed as it was in almost every detail (well, the painted chair was actually done with oil paint squeezed directly from the tube rather than Day-Glow, and the first two artists mentioned are in fact acquaintances of mine rather than people whose work was included in the clutter); but it doesn’t matter, because I would have altered any and all details as necessary. I loath the notion of the "true story." There’s no such thing. Art is artifice, and the poets are makers, not just livers. But yes, there really was a cockroach in the wall.

AAK:What role does humor play in your work?

GB:Humor is a form of uneasiness. It’s the reaction of people in an uncomfortable position, the resort of the helpless, the threatened, the weak and the doomed. Those adjectives pretty much sum up the human predicament, and so humor is a human and humanizing reaction to the difficulties of everyday life. Humor is a form of ambiguity, and ambiguity is the stuff of poetry.

AAK:Do you have a favorite poem in this collection? If so, which, and why does it stand out from the others?

GB:Hmm. Favorites get chosen for all of the wrong reasons. For example, there’s a poem in my previous volume with Knopf called "Paideia." Prior to book publication, it used to come back regularly from various magazine editors with notes of minimal politeness (not, I assure you, an unusual event); but once it came back from a very well-known magazine with a little letter admonishing me for sending in something so flippant. Well, it is flippant, but it’s also deeply serious. The poem instantly became a favorite of mine, and in fact it’s proven popular at readings. In the current volume, there’s a poem called "Apologia" which operates in some of the same way. Otherwise, I tend to like the poems which are too abstract for most people, because to me they seem to address what I’m interested in most directly. In the current volume, "Spagyric" would be one such.

AAK:You’ve been a construction worker, a sommelier, and an ad copywriter. How did you end up as a poet?

GB:I like to think I have done these things, not been them. It’s the norm rather than the exception for poets to dabble in many professions, because being a poet is just like any other job, except that you don’t get paid for it. The way to become a poet is by persistence unto folly. The poem, "How I Got in the Business" in the current volume takes a look at all this. As for how I’ll end up as a poet, I don’t know, but one shudders to think.

AAK:Are your presently working on a new collection of poems? If so, could you tell us about it?

GB:The poet is always working, because the poet is always observing. Emerson says the poet’s mind is like a branch sticking out into the current of a stream: all manner of objects accumulate there, though more or less at random. But poets are not novelists or non-fiction writers. They don’t work up a project with their agent and hire a research team. They just plod along day by day until the pages in their manuscript approach book length. The accumulation doesn’t make good copy, and even the selection committees for fellowship and foundation grants like poets to describe the book in process. Poets then have to invent something that sounds good. What are they meant to say, the truth? "I want money so I can stare out the window a long time, read some other poetry, look at my list of title ideas, and see if an idea arrives." Staring out the window is what I do. Walking around town is what John Ashberry does. A lot of poets drink too much while waiting for ideas; drinking too much while listening to loud music was what Hart Crane did.