TEACHING GUIDE

NOTE TO TEACHERSIn

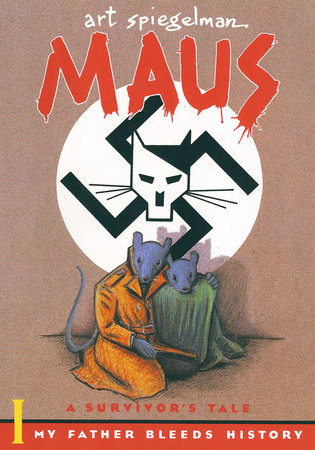

Maus I: My Father Bleeds History Art Spiegelman has simultaneously expanded the boundaries of a literary form and found a new way of imagining the Holocaust, an event that is commonly described as unimaginable. The form is the comic book, once dismissed as an entertainment for children and regarded as suited only for slapstick comedy, action-adventure, or graphic horror. And although

Maus includes elements of humor and suspense, the horror it envisions is far worse than anything encountered in the pages of Stephen King: it is horror that happened; horror perpetrated by real people against millions of other real people; horror whose contemplation inevitably forces us to ask what human beings are capable of perpetrating—and surviving.

Maus has recognized the true nature of that riddle by casting its protagonists as animals—mice, cats, pigs, and dogs. As Spiegelman has said (in an interview in The New Comics, p. 191): "To use these ciphers, the cats and mice, is actually a way to allow you past the cipher at the people who are experiencing it." When

Maus first appeared as a three-page comic strip in an underground anthology, the words "Nazi" and "Jew" were never mentioned. Spiegelman’s animals permit readers to bypass the question of what human beings can or cannot do and at the same time force them to confront it more directly. His Jewish mice are a barbed response to Hitler’s statement "The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human." His feline Nazis remind us that the Germans’ brutality was at bottom no more explicable than the delicate savagery of cats toying with their prey. And although Vladek Spiegelman and his family initially seem even more human than the rest of us, as the story unfolds they become more and more like animals, driven into deeper and deeper hiding places, foraging for scarcer and scarcer scraps of sustenance, betraying all the ties that we associate with humanity.

Many books and films about the Holocaust founder on its hugeness: those caught up in it blur into a faceless mass of victims and victimizers. But

Maus is the particular story of one survivor, Vladek Spiegelman, a young man who treated his mistress badly and may have married for money, whom we first see in his stubborn, tight-fisted, infuriatingly manipulative old age. Because he is not a saint, what happens to Vladek is all the more horrible. And by its very nature the comic book is a specific medium, in which even the slightest background details tell a story of their own. Students who read

Maus will come away knowing the workings of the ghetto black market, the architecture of false-walled bunkers, and what was happening in the town squares where Polish Jews lined up patiently for deportation. They will know the words on the sign above the gate to Auschwitz: "Arbeit Macht Frei"—"Work Makes You Free."

In addition,

Maus is the story of the aged Vladek’s tortured relations with his son, Artie, who is both a character in this book and its narrator; with his first wife, Anja, who killed herself twenty-three years after leaving Auschwitz; and with his long-suffering second wife, Mala, who reminds Artie that Vladek’s cheapness and paranoia are not wholly attributable to his ordeal. The elderly Vladek’s conversations with his son give the Holocaust narrative a frame and also an ironic depth. Vladek and his son are at odds, and what stands between them is Vladek’s unexamined past, which has left deep wounds in both of them.

Maus is subtitled "a survivor’s tale," and the survivor is not just Vladek; it is also his son. In reading this simple book, students are driven to ask large and complex questions about the nature of survival, about suffering and the moral choices that people make in response to it. They are compelled to consider the terrible relation between history and the real human beings who are history’s casualties.

ABOUT THIS AUTHORArt Spiegelman is co-founder/editor of

Raw, the acclaimed magazine of avant-garde comics and graphics. His work has been published in the

New York Times,

Playboy, the

Village Voice, and many other periodicals, and his drawings have been exhibited in museums and galleries here and abroad. Honors he has received for

Maus include a Guggenheim fellowship, and nomination for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Mr. Spiegelman lives in New York City with his wife, Francoise Mouly, and their daughter, Nadja.

DISCUSSION AND WRITINGPrologue1. What is your first impression of Vladek Spiegelman? What does his remark about friends suggest about his personality? How does it foreshadow revelations later in the book?

The Sheik1. What has happened to Artie’s mother?

2. How does Vladek get along with Mala, his second wife? What kind of things do they argue about?

3. How long has it been since Artie last visited his father? What do you think is responsible for their separation?

4. How does Vladek respond when Artie first asks him about his life in Poland? Why might he be reluctant to talk about those years?

5. On page 12 we see a close-up of Vladek as he pedals his exercise bicycle. What is the meaning of the numbers tattooed on his wrist? How does this single image manage to convey information that might occupy paragraphs of text?

6. Describe Vladek’s relationship with Lucia Greenberg. How was he introduced to Anja Zylberberg? Why do you think he chose her over Lucia?

The Honeymoon1. What is Vladek doing when Artie comes to visit him? How does his health figure elsewhere in the book?

2. How does Vladek become wealthy?

3. What does Vladek see while traveling through Czechoslovakia?

4. Why does the artist place a swastika in the background of the panels that depict the plight of Jews in Hitler’s Germany (p. 33)? Why, on page 125, is the road that Vladek and Anja travel on their way back to Sosnowiec also shaped like a swastika? What other symbolic devices does the author use in this book?

Prisoner of War1. When Artie refused to finish his food as a child, what did Vladek do? How does he characterize Anja’s leniency with their son?

2. Why was Vladek’s father so reluctant to let him serve in the Polish army? What means did he use to keep him out?

3. What is the meaning of the beard and skullcap that Vladek’s father is shown wearing in the panels on page 46? What happens to his beard later on?

4. How does Vladek feel after shooting the German soldier?

5. How did the Germans treat Vladek and other Jewish prisoners after transporting them to the Reich? How was this different from their treatment of Polish P.O.W.’s?

6. What is the significance of Vladek’s dream about his grandfather? What recurring meaning does "Parshas Truma" have in his life?

7. How does Vladek arrange to be reunited with his wife and son? What visual device does Spiegelman use to show him disguising himself as a Polish Gentile?

The Noose Tightens1. Describe the activities depicted in the family dinner scene on pages 74-76. What do they tell you about the Zylberbergs?

2. Although Jews were allowed only limited rations under the Nazi occupation, Vladek manages to circumvent these restrictions for a while. What methods does he use to support himself and his family?

3. During the brutal mass arrest depicted on page 80, Vladek is framed by a panel shaped like a Jewish star. How does this device express his situation at that moment?

4. What happened to little Richieu? When Vladek begins telling this story on page 81, the first three rows of panels are set in the past, while the bottom three panels return us to the present and show the old Vladek pedaling his stationary bicycle. Why do you think Spiegelman chooses to conclude this anecdote in this manner?

5. What happened to Vladek’s father? What does the scene on pages 90-91 suggest about the ways in which some Jews died and others survived?

Mouse Holes1. This chapter and the one that follows both have the word "mouse" in their titles. And, in fact, in the concluding sections of this book Spiegelman’s mice seem to become more "mouse-like." How does the author accomplish this? What reason might he have for doing so?

2. Why does Artie claim that he became an artist?

3. How does the comic strip "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" depict Artie and his family? How did you feel on learning that Artie has been hospitalized for a nervous breakdown? Why do you think he has chosen to draw himself dressed in a prison uniform? What is the effect of seeing these mice suddenly represented as human beings?

4. Why did Anja finally consent to send Richieu away? Was his death "better" than the fate of the children depicted on page 108?

5. Describe the strategies that Vladek used to conceal Anja and himself during the liquidation of the ghetto. How did the Germans flush them from hiding?

6. What eventually happens to the "mouse" who informed on the Spiegelmans? What becomes of Haskel, who refused to save Vladek’s in-laws even though he accepted their jewels?

7. What does the incident on pages 118 and 119 tell us about relations between Jews and Germans? Does the knowledge that some Nazis fraternized with their victims make their crimes more or less horrible?

8. How did Vladek care for Anja after the destruction of the Srodula ghetto? Contrast his behavior toward his first wife, during the worst years of the war, with the way he now treats Mala.

Mouse Trap1. What does Vladek mean when he says that reading Artie’s comic makes him "interested" in his own story (p. 133)? Is this statement just a product of broken English, or does it reveal some deeper truth about what happens when we record our personal histories?

2. On page 136 Vladek says that he was able to pass for a member of the Gestapo but that Anja’s appearance was more Jewish. What visual device does Spiegelman use to show the difference between them?

3. Given the fact that the Spiegelmans are "mice," what is the significance of the panels on page 147, in which Vladek and Anja’s hiding place turns out to be infested with rats? Why might the author have portrayed this incident?

4. On page 149 Vladek is almost betrayed by a group of schoolchildren. What stories did Poles tell their children about Jews? How do you think such stories—and perhaps similar stories told by German parents—helped pave the way for the Final Solution?

5. Why does Vladek want to flee to Hungary? How are he and Anja eventually captured? What is the significance of the letter from Mandelbaum’s nephew (p. 154)?

6. Why does Artie call his father a murderer? Is he justified? Who else has he called a murderer, and why?

The characters of Maus I 1. What kind of man—or mouse—is Vladek Spiegelman? What details does Spiegelman use to establish his character? What traits do you think enabled him to survive events in which the overwhelming majority of Jews were killed?

2. The opening pages of

Maus portray Vladek Spiegelman as an old man. Only later, when Vladek is telling his story, do we see him as he was in his thirties. What differences do you see between the old Vladek and the young one who emerges in his memories? How do you account for these changes in his character?

3. How does Spiegelman establish the old Vladek’s "foreignness"? In what specific ways, for example, does his speech differ from his son’s? Why does the author show the young, remembered Vladek, as well as his family, speaking "normal" English?

4. How would you sum up the character of Artie? How would you compare him with his father? What things about Vladek irritate him? Which of Artie’s traits does Vladek seem incapable of understanding? In what ways do you think Vladek has influenced his son?

5. How does the author portray Anja as a young woman, and later as a depressed and suicidal older one? How are your earlier perceptions of her altered by the comic-within-a-comic "Prisoner on the Hell Planet"? If Anja had written a suicide note, what might it have said?

For in-class discussion 1. What does

Maus do that pure text narratives cannot? In what ways do Spiegelman’s crude drawings help us visualize things that words alone, or more "realistic" images, might be unable to portray? How does

Maus differ, both in its subject matter and visual format, from other comic books you have read?

1. One of the problems inherent in representing human beings as cats and mice is that animals have a narrower range of facial expression. Are Spiegelman’s animals as emotionally expressive as human characters might be? If so, what means does the cartoonist use to endow his mice and cats with "human" characteristics?

2. On page 23, Vladek asks his son to refrain from telling the story of his youthful involvement with Lucia Greenberg, claiming that "it has nothing to do with Hitler, with the Holocaust." Artie argues that this story "makes everything more human." Which of these statements do you agree with? Should the Holocaust be treated as an event so catastrophic that it makes private experience irrelevant? How do other books and films about the Holocaust, like Schindler’s List, Night, or The Painted Bird, deal with this predicament?

3. Why do you think some Jews assisted the Germans, either by policing the ghettos or by informing on their people (see pp. 113 and 117)? Why might Vladek still send gift packages to Haskel, who betrayed his in-laws (p. 118)? In Vladek’s place, would you do the same thing?

4.

Maus contains several moments of comedy. Most of these take place during the exchanges between Artie, Vladek, and Mala. But humor even finds a place in the ghetto and the bunker, for example on page 119, when the cake sold to the starving Jews of Srodula turns out to have been made with laundry soap. What is the effect of this humor? Was it inaccurate or "wrong" of Spiegelman to have included such episodes within his survivor’s tale?

SUGGESTED ACTIVITIES1. Keep a journal recording your responses to

Maus I. If you were initially startled or put off by seeing the cartoon format used in the service of material that is profoundly serious, did those feelings change in the course of your reading? At what point, if any, did you find yourself accepting Spiegelman’s visual and dramatic conventions? You may wish to put away your journal for a few weeks and then reread them, while skimming through

Maus a second time. Do the responses you first recorded still hold true? In what ways has the book stayed with you?

2. On page 33, a character says, "There’s a pogrom going on in Germany today." The Random House Dictionary defines "pogrom," a word of Russian origin, as "an organized massacre, especially of Jews." Elsewhere it defines "the Holocaust" as "the systematic mass slaughter of European Jews in Nazi concentration camps during World War II." How well do these definitions describe the events through which Vladek Spiegelman lived? Using independent research, describe the difference between a pogrom and the Holocaust. Why are such words—along with others like "victim," "survivor," and "genocide"—considered controversial today?

3. The situation of Polish Jews worsens steadily and dramatically throughout

Maus, a deterioration that is aptly summed up by the chapter heading "The Noose Tightens." Chart the progress of this escalation, citing specific incidents in the book. What happens to Spiegelman’s mice as they are forced deeper into "mouse holes"? In what way do they become more "mouse-like"? How might they have responded differently if the Germans had begun their program of mass extermination from the start?

4. Most art and literature about the Holocaust is governed by certain unspoken rules. Among these are the notions that the Holocaust must be portrayed as an utterly unique event; that it must be depicted with scrupulous accuracy, and with the utmost seriousness, so as not to obscure its enormity or dishonor its dead. In what way does

Maus obey, violate, or disprove these "rules"?

5. Over the next month, interview a parent or grandparent about an episode of his or her life. Record not only the story that emerges, but your responses to that story. In what way is that story also your own?

ABOUT THIS GUIDEThis teacher’s guide was written by Peter Trachtenberg. Peter Trachtenberg has taught writing and literature at the New York University School of Continuing Education, the Johns Hopkins University School of Continuing Education, and the School of Visual Arts.

COPYRIGHTCopyright © 1994 by PANTHEON BOOKS