A Conversation with Hampton Sides, Author of AMERICANA

Q: Why the title “Americana”?

A: The book has the feel of an extended road trip. I’ve spent much of my life roaming around observing the quirks of modern American culture. Putting together this collection has given me a chance to look back on more than a decade of dedicated wandering. I think “Americana” also reflects something about the country’s mood right now in this acutely interesting election year. Since 9/11, we’ve all heard that we live in patriotic times. As we muddle through two very complicated wars, deal with the hue and cry over the Patriot Act, and experiment with ambitious nation-building on the other side of the planet, we’ve never been more concentrated on the question of who we are as a nation. What do we stand for? What are our strengths? What about us is likeable and unique?

Q: What are some of those qualities?

A: I think of America not so much as a single country but as a constellation of groups out there competing for air time, energetically expressing themselves and luxuriating in their right to govern themselves. Freedom is that great vaunted word that’s always applied to our country—and rightly so. It’s what gave us our greatest quality: the impulse toward invention and the improvisational spirit to push out across all sorts of frontiers. This book, at its essence, is about American freedom. It’s about what we do with our freedom, how it gets translated—sometimes humorously, sometimes nobly—into American life.

Q: Jonathan Yardley called you “the scribe among our tribes.” What did he mean by that?

A: Much of my journalism is about subcultures. America is an archipelago of tribes, a land where people form national families of kindred spirits. That was one of the most perceptive comments Tocqueville made about America—that we form our own little fraternities with amazing ease. We make our own worlds. Observing those worlds has been one of my professional obsessions. I’ve sort of been an anthropologist of modern America, in a non-academic way. Whether it’s Marines or Tupperware salesladies, high end audiophiles or bike couriers, I’m fascinated by the hallmarks of the American tribe.

Q: Where do you think you cultivated this fascination?

A: It has something to do with growing up in Memphis, this humid cotton town on the river where black and white cultures have been in the blender, stuck on “puree,” for a long time. Birthplace of the blues, rock n’ roll, and soul. Watching the Elvis pilgrimage phenomenon well up after his death, the great freakshow with the fans coming to Graceland by the thousands every August—this gave me certain ideas at a young age about how quickly America spawns national tribes. It also made me pretty tolerant around odd people. A reviewer said my being from Memphis gave me “an aplomb in the face of exceedingly idiosyncratic behavior.” I like that.

Q: What do these tribes have in common?

A: Often they have an epic national reunion that brings them back, year after year. A lot of the stories in Americana are just me going to these pageants and festivals and feasting on the spectacle, the pure tribal wattage. Also, most of these groups have a charismatic founder, someone who had the force of personality to make an idea stick through time. Like Wally Byam, the founder of Airstream; Tony Hawk, the de facto king of skateboarding; Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet; Brownie Wise, who gave us the Tupperware party; or Ray Scott, the man put bass fishing on the national map. Many of the pieces in Americana are profiles of the patriarchs and matriarchs of their tribes.

Q: How did the idea of creating this collection come about, and why now?

A: After I wrote Ghost Soldiers, and became known for writing a certain kind of dark historical narrative, I realized there was a completely different facet of my writing that wasn’t getting out to readers. In my journalism, I often get myself into ridiculous situations, and I have a lot of fun with my subjects. This collection was a way for me to show other sensibilities that are a real part of who I am as a writer. There’s a lot of stuff in this book that, I hope, will make readers laugh. As for the timing, it was a question of when had I accumulated enough good stuff that would add up to something greater than the sum of its parts? And the answer to that was, Not until very recently. Although I’ve been working this vein for a decade, a third of this book was written in the last two years, after Ghost Soldiers was published.

Q: Are there thematic similarities between GHOST SOLDIERS and the material in AMERICANA?

A: The central theme of Ghost Soldiers is the limits of human endurance and the astounding ways in which people survive in the face of steep odds. That theme constantly crops up in Americana. Probably the best example is “Points of Impact,” a story that was nominated for a National Magazine Award, in which I follow the lives of three survivors of the World Trade Center disaster through their ordeals and recoveries. In the story “Ghosts of Bataan,” I go back to the Philippines to trace the route of the Bataan Death March with several characters from Ghost Soldiers. I found it humbling to walk the terrain with these extraordinary guys who’d survived that harrowing experience and lived to a ripe old age.

Q: You were going to embed with the Marines in Iraq but declined at the last minute. Why?

A: When I wrote about that for The New Yorker, people assumed it was protest journalism. It’s true that I had major doubts about the war. But that had little to do with it. I was just plain scared. I got over there and learned I was going to be on the front lines with an outfit called First Recon. If Saddam had WMD it seemed obvious he’d use them on us, the invaders. I felt like a lab rat, coming along to observe—and breathe—whatever Saddam might sling at us. The sum total of my experience with my chem equipment was a 30-minute seminar on a Kuwait tennis court, in which I learned, among other things, that if I barfed in my gas mask I was probably a goner. I stayed up all night at my hotel thinking about the disturbing logic behind this war and realized that—you know what?—I hadn’t signed a contract with the Marines and was free to leave.

Q: What did you do after you decided not to embed?

A: A few days after the start of hostilities, I began to investigate a story about the first American combat casualty of the ground war, who turned out to be a beloved Marine platoon commander named Lt. Shane Childers. One of the longest pieces in Americana (“First”), it’s a profile of his life intercut with a second-by-second depiction of his death in the Rumaila oil fields. Had I embedded, I would have been very close to where Childers died and likely would have encountered the same resistance that killed him.

Q: Many pieces here first appeared in Outside. What are your ties with the magazine?

A: I’m editor-at-large for Outside, which means they send me all over the planet on interesting projects. It’s a dream job, basically. Years ago, I was a full-time editor at Outside. It’s one of the most adventurous journals around and wins more than its share of National Magazine Awards. Outside publishes some of the best practitioners of non-fiction—people like Tim Cahill, Jon Krakauer, Bill Bryson, Ian Frazier, David Quammen. Working with some of these writers has been a huge influence.

Q: Aside from Outside, what other writers have had a major influence on your journalism?

A: Probably the biggest influence on my career was the late John Hersey, who, while he was at The New Yorker, wrote one of the masterpieces of narrative non-fiction, Hiroshima. Hersey was a teacher of mine at Yale, and a friend. He got me to see the possibility of journalism not just as a business but as an art form. I modeled “Points of Impact” after Hiroshima. And in the end, I decided to dedicate Americana to John.

Q: Of the pieces in AMERICANA, which has had the most profound influence on you?

A: Writing “Points of Impact” just devastated me. It forced me to understand 9/11 from the most excruciatingly personal perspective—from the point of view of three people who barely made it out alive and who will be forever stamped with the residue of that unbelievable day. I flew to New York a few days after it happened and spent months interviewing people. Until I met these survivors and heard their stories, I couldn’t fathom this event. It reminded me of the truism that history is, above all, personal.

Q: What were some of the more bizarre things you experienced during your travels?

A: Getting kicked out of the National Spelling Bee headquarters in Cincinnati for being a “satirist.” Witnessing the science-fiction theater the morning the Biospherians emerged from their geodesic ark in the Arizona desert. Maybe the most bizarre experience was being in a room full of 5,000 shrieking, squealing Tupperware salesladies in Florida as the company unveiled its new product line. It was as though a fever had swept the room. I was the only man in the whole convention hall and I felt at any moment the women were going to turn on me in a frenzy, like in The Bacchae, and rip me limb from limb.

Q: Is it true that GHOST SOLDIERS is now being turned into a movie?

A: Miramax has produced a film that’s based in part on my book as well as on other sources. Tentatively titled The Great Raid, it’s supposed to come out in the fall. It stars Joseph Fiennes, Benjamin Bratt, and Connie Nielsen, and is directed by John Dahl (The Last Seduction, Rounders). I’m a historical consultant, and what I’ve seen of it looks fantastic.

Q: What’s next for you as an author?

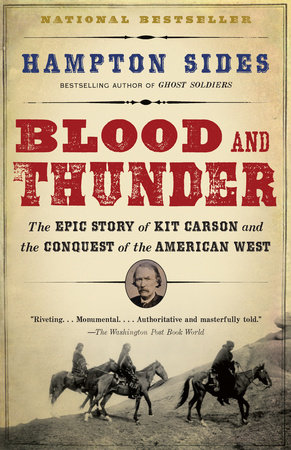

A: I’m working on a narrative history about Kit Carson and the conquest of the Navajos during the Civil War. You could say it’s about the ultimate American “tribe”—the Navajo Nation, which is basically a country unto itself. Like Ghost Soldiers, it’s a story about war and resilience during a long, hard exile—and finally, about redemption.