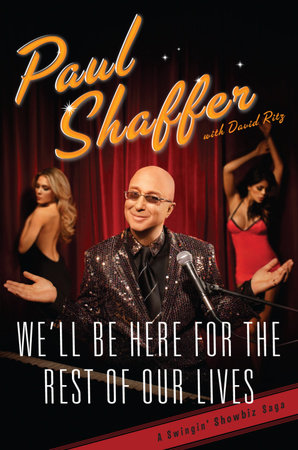

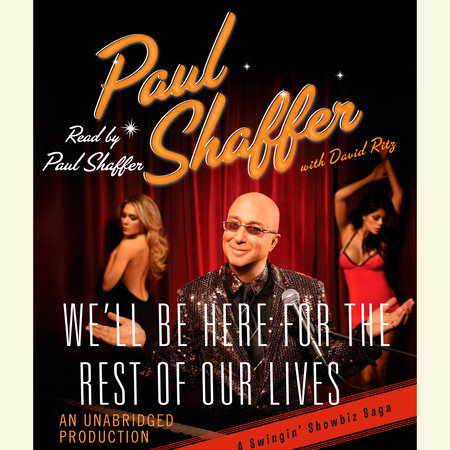

Author Q&A

A Conversation with Paul Shaffer

Author of WE’LL BE HERE FOR THE REST OF OUR LIVES:

A Swingin’ Show-Biz Saga

Paul Shaffer: I had the kind of Jewish parents who insisted that their kid be musical. My mother played Chopin, Rachmaninoff, and of course the Mary Martin and Ethel Merman at Carnegie Hall live album. On Sundays, my dad would put on the best jazz vocalists: his favorite Sarah Vaughn, Billy Eckstein and Ray Charles, who, he taught me, was a genius. For folks who lived up on the north shore of Lake Superior, their taste in music was pretty damn hip. They started me on piano lessons at six; my mother said, “When he can read English, it’s time for him to read music.” After one lesson, I started to pick out tunes on the piano by ear, fascinated to discover that the notes of the scale could be used to play songs that I liked, not just those I had to play for my lesson. Then I heard rock ‘n’ roll on the radio, and it was all over, I became obsessed. When I figured out the three basic rock chords, I could play all the songs. I would come home from school and bang them out on the piano as loud as I could, so the sound just got all up in my ears. When I got a little older, I didn’ t buy 45s, I just learned them off the radio. I would recreate the whole sound, all the parts, with my hands.

Q: How did the conflict between your parents’ love of music and your father’s dictum that “passion (for music) doesn’t equal income” affect you?

Paul: My parents were just as conflicted as I. As much as they impressed on me the need for a real job and profession, when I said, I have to give show business a try, they were secretly thrilled. They loved music and show biz. The popular Canadian comedy team Wayne and Shuster performed a bunch of times on “Ed Sullivan,” and my dad had been the vocalist for Wayne and Shuster when they did college shows. But it was the Depression, so he became a lawyer for the security. My first year at the University of Toronto, I had given up my rock band and didn’t have a musical outlet. I was very depressed, exhausted and sleeping all the time. Then I started playing in an esoteric jazz group and I cheered up right away. That’s when I knew that I had to give music a try. So I made that deal with my dad: Give me a year, then I’ ll go to grad school. I kept learning, opening up my ears beyond the strictures of rock and roll, started to love Coltrane, and appreciated the spirituality of it, the sense of searching and communicating through jazz. I was also playing topless bars, weddings, anything I could. Just before my year ran out, I fluked into this job conducting “Godspell,” the ‘70s rock musical of the St. Matthew gospel–Jesus set to a rock score.

Q: Right–doing a favor for a friend catapulted you from playing a seedy strip joint to a new career as musical director for the cutting-edge rock musical “Godspell” and then on to “NBC’s Saturday Night Live.” Tell us about that.

Paul: Steven Schwartz, the Broadway composer of “Wicked” and “Pippin,” changed my life. He hired me in Toronto for his show “Godspell” and said, “When this show’s over, I’m bringing you to New York; you belong in New York.” He got me my visa and I played for him in “The Magic Show” on Broadway. Then Howard Shore, the movie composer and later an Oscar winner for the “Lord of the Rings” score, called and said, “I’ m coming into New York to do a new thing called ‘Saturday Night Live.’ I need a piano player, you’re in town, and you already know a lot of the people on the show.” In “Godspell” in Toronto, I had met these superbly talented, funny people who are still my best friends–Martin Short, Eugene Levy, Andrea Martin, the late Gilda Radner, Dan Aykroyd, and Victor Garber. I knew John Belushi; he was one of first guys I met when I came to New York and Billy Murray’s older brother Brian Doyle Murray introduced me around to the National Lampoon crowd. I told Howard I didn’t read music that well. He said, “You’re a natural. I want you for what you can bring to it,” and he talked me into taking the gig. The next thing I knew I was on TV.

Q: Tell us how a near-fatal car crash led you to Letterman.

Paul: I did “Saturday Night Live” for its first five years, going from rehearsal pianist to writer of special musical material, to a featured player. I had learned a little bit of how to be funny from all of my friends; I cherished their humor to such a degree that some rubbed off I think. After five years, when everybody left including Lorne Michaels, it didn’t make sense to stay and start over with a new cast. I was freelancing, doing studio work that was also very exciting to me, working with Yoko Ono, Diana Ross, and Burt Bacharach. On the second day of a trip to Hawaii with my lovely girl friend Cathy, who is now my wife, I was seriously injured in a bad car accident and woke up in an oxygen tent in Honolulu. I went right back to work playing gigs and sessions, but it took three years to recover. Then I get this call about Dave Letterman starting a show that would air even later than Johnny Carson, which seemed perfect for me. I dragged myself in. Even to this day, Dave says, “Yeah, you were skinny; I didn’t know what the hell was wrong with you, but I knew I wanted to hire you.” He had seen some of the bits I had done on “Saturday Night Live,” specifically the skits with Bill Murray as the lounge singer. So, Billy was our first guest, and he sang “Let’s Get Physical” doing jumping jacks. He never rehearsed. I didn’t even know what key to play it in; I just guessed. I never thought that professional show business would be so seat-of-your-pants unrehearsed, but it sure was, and I was ready for it from experience with improvisational comedy–starting with a premise and running with it.

Q: As a musical director, what’s your worst nightmare? What is your favorite aspect of preparing for a special musical performance? For your nightly Letterman show appearance?

Paul: I have experienced my worst nightmare several times. The great Anthony Newley had come on Letterman when we had a running bit with celebrities singing their version of a theme song, written by Mancini, for when we answered viewer mail. Newley was always singing about “the clown, he’s crying on the inside, laughing on the outside,” so we started with him singing the mail song, and I’m playing by ear, and somehow I modulated into the “clown” section way above Newley’s range. But he’s such a pro and his ear is so good, he follows me into this new key, goes for this super-high ending note, and hits it. I think he hurt himself it was so high. I was just dying. Once, on “Saturday Night Live,” John Sebastian came up to the mike to sing his “Welcome Back” with the house band. The mike squealed with feedback, and he backed off, and it seemed like an hour went by on live television with those lead-in chords playing before finally we started again. On the musical performances, I just love every second; I love all kinds of music and I’ve gotten to play with everyone from Snoop Dog to Bruce Springsteen to Placido Domingo. On Letterman, I love that it continues to be just as unrehearsed as that first show with Bill Murray. Dave likes it that way. He is the quickest mind in show business, and I get to talk to him on air, and anything could happen, any night. That anticipation, that possibility is what keeps it fun.

Q: Do you ever wonder “what if” you had taken the George Costanza role that Jerry Seinfeld offered you?

Paul: You know, I’m the biggest jerk in the world for not calling back, but I had a little experience as a sitcom actor in the ‘70s on a show called “A Year at the Top,” produced by Norman Lear and Don Kirshner. It was going to be a Monkees-type show about kids in a band, and because I was musician, I got the part. Had it been a success, we might have been like the Jonas Brothers doing shows and records along with the sitcom, but there still wasn’t enough music for me. I was missing music; music really is where my heart is. Of course, it turned out to be the most beloved show and I’m happy to say things turned out OK between Jerry and me.

Q: What was the best piece of unexpected advice you ever received and who shared it with you?

Paul: The advice came from John Belushi. In “A Year at the Top,” my character was constantly walking into a scene being astonished by something, and the only way I knew how to act surprised was with my mouth agape. After the first show aired, Belushi said, “Stop acting with your mouth; use your eyes.” It was especially ironic because John then went on to make the Blues Brothers movie in which his eyes were entirely obscured by sunglasses for the entire film.

Q: Of your many memorable experiences with music and showbiz legends, celebrities, and royalty, which person would you say had the greatest impact on who you are as a musician? As an individual?

Paul: My favorite musician to play with certainly was James Brown. I was such a big fan of his as a kid, and I still am. He invented the sound that we’re still dancing to today, whether you call it house or techno or electronica–it’ s all his rhythms. Nothing really has changed except we use computers today, but it’s still James Brown. I never thought I would be in the middle of music that was so funky, when I got to play with him and he started to sing and shake his ass, you just couldn’t help but get funky. Playing with him was my biggest thrill.

As far as an influence on me–Miles Davis comes to mind. His music has always fascinated me, especially when he went electric and combined the funk rhythms of James Brown and Sly Stone with his own jazz–the hippest jazz on the planet. Then I got to play with him in the studio, and see him arrange. He was so encouraging. I was way out of my league playing with him in the first place, but he was straight ahead. He said to me, “If it ain’t funky, you can’t use it, right Paul?” That was one of the greatest compliments I ever got. I saw how he dealt with musicians to bring the best out of them. People used to complain about how Miles Davis would sometimes turn his back on his audience. I realized that he was presenting not just his own playing, but the music of his whole band. He was conducting, facing the band, bringing out the best in them, encouraging them. He had such confidence, he didn’t have to grandstand to steal the show; it was always about the sound for a jazz player like him. But then, he always looked great. He was quoted as saying, “When you come on stage, the audience has got to know you can play before you put the horn up to your mouth.” So appearance was very important to him, too.

Q: Who in the music world today would you like to hear more from?

Paul: There’s a record out there that I love that’s big right now–Keri Hilson’s “Knock You Down.” I like Pharrell Williams from the Neptunes. He is a producer, primarily; I like anything that he does. And I think that Britney Spears makes brilliant records. Some people put her down, but you can’ t argue with how terrific her records are–“Circus,” “Womanizer,” “Toxic,” I love all of those.

Q: What in the book will most surprise people to learn about you?

Paul: I think the Letterman show is very transparent, in that, you can tell how we’re feeling, what we’re thinking; it’s all right there. We are true reality television. I have a feeling that the Real Housewives are not so real after all; I think all these shows obviously have a story arc, with scene outlines, just like we had in “Spinal Tap.” Our show is absolutely real, so I don’t think anyone will be so surprised by any one thing. I’m living this incredible life, meeting and performing with the most gifted and talented people on the planet. I have been very honest, and I think a person might close the book and say, “Well, that explains everything.”

Q: Who and what inspired you early on toward music?