Author Q&A

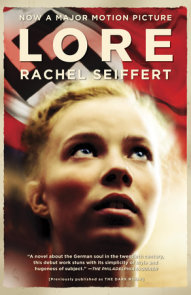

A Conversation with Rachel Seiffert,

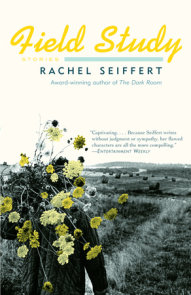

Author of THE DARK ROOM

Q: After working in film for a number of years, what drew you to writing? What led you to write THE DARK ROOM?

A: My film “career” is pretty speckled. I worked as an assistant editor, have edited, written and directed short films, and I also worked for 2 years as a project co-ordinator for an organisation which funds and supports new filmmakers. I wrote alongside all of these jobs, and like this combination: the privacy and freedom of the writing process, the collaboration and contact with other human beings in my working life.

As to what led me to write this novel:

I am half-German. I grew up in England, but was brought up bilingual, holidays and festivals were always celebrated German-style, and we visited Germany very regularly. I have always been close to my German family, despite the distance, and have always been aware of the German part of my identity.

My family was very open with me about the Third Reich and the Holocaust. My mother and her sister, for example, were both very active in the peace movement when I was a child, and so it was important to them both personally and politically that I knew what had happened, what was done.

At primary school, in England, I was bullied for being a “Nazi,” and so from a very young age, I had a strong sense that being German was bad, even before I really knew anything about the Holocaust. The desire to equate German with evil is persistent. Even within Germany, where I now live. There has been a steady rise in right wing violence since reunification and sometimes I hear people talking with despair, asking themselves whether this tendency might not be something inherent within Germans.

I think this is understandable. The scale of the Holocaust is incomprehensible. It is hard to believe that it was committed by human beings, that genocide is made up of millions of individual acts of murder. By naming the Holocaust an act of evil we dehumanize it. In doing so, we express our horror at what was done. But perhaps we also take away the very human element of individual responsibility. Nazis, however sadistic, however incomprehensible their politics and acts, however much they tried to mechanize death/murder, they were also human beings.

This is the seed of the book, as it were; the point of departure into fiction. The three protagonists in the novel offer three different perspectives on or approaches to this same, basic issue.

Q: In researching for this novel, did you, like Micha, the protagonist of Part III, interview many people and spend weeks reading library texts and watching documentaries? Did you run into many of the same difficulties as Micha?

A: Yes, I spent weeks reading books in libraries and watching documentaries, and spoke a lot with family members. I am not sure what you mean by difficulties. If you are asking whether it was painful, then the answer is yes. There were times when I could only read and not write, and times when I felt I couldn’t read or see any more.

Micha’s task is so painful because it is personal. The process is difficult for him because the things he reads, sees and hears all relate to the grandfather whom he loves so much. His search also hurts his mother, father, grandmother, sister and partner, and so he puts a great deal at risk by placing so much importance on uncovering the past. For Micha, and for those around him, his search does not necessarily bring clarity or certainty, but it certainly brings pain.

Q: Throughout the novel, there are numerous references to photographs, to cameras, and to the process of photography (taking and developing pictures), and to darkrooms. Did you choose this title to perpetuate this reference, and to connect the novel with the process of clarifying things (developing photos) and documenting things (taking photos, keeping photos)? What is the dark room? Why did you choose this title?

A: As you say, the title plays on the photo theme, but the dark room is also the place where memories and events too painful to recall are kept hidden. For Helmut, it is the uneasiness about the drain of people out of Berlin, the changing shape of his city home. For Lore, it is the unsettling connection between her parents, Tomas, and the photos of the concentration camps. For Micha, and for his family, it is the possibility of guilt lying very close to home.

The photo theme was not a conscious choice. I, like all people born after 1945, have a perspective on the Third Reich and on the Holocaust which is very strongly influenced by photos from the period. I grew up with family stories, and my visual memory bank is also full of family portraits and snapshots, but contemporary press and amateur photos also strongly inform what I know about that time. Mina, one of the characters in the third story, mentions a photo of a small boy taken at the liberation of Bergen Belsen — just one example of the images which are always there in my mind when I think about the Holocaust.

I am not sure that I am comfortable with the idea of my book “clarifying” and “documenting”. For one thing, it is fiction, and I think it is dangerous to lend any work of fiction too much authority. For me, the photo theme is more about the desire to clarify and document, and the impossibility of this process. Helmut’s pictures of the Roma being transported don’t show the full horror of the scene as he experienced it, for example, and Lore dreams about the emaciated bodies she sees in the newspaper photos, but does not understand who they were or who killed them.

Q: You call THE DARK ROOM a novel. What binds the three stories together?

A: Definitions are difficult. I don’t know how important that is to readers — it will be interesting to find out. I am not really sure what I call The Dark Room. “A novel”, “a novel told in three stories”, just “a book”, maybe. I suppose calling it a novel is convenient because that conveys that is prose fiction.

The word used to define the book is not important to me, but I do consider the book to be not three different stories, but a single, whole piece of fiction.

The stories are distinct, but related thematically. Family, responsibility, denial, love. For me, each informs the other, and this is one reason why it is a novel, a whole. That Micha’s family did not question the past, for instance, can perhaps be appreciated through Lore’s fear of connecting her parents to the crimes she hears people talking about on the trams.

I also don’t think that the significance of the Third Reich and the Holocaust can be appreciated from any one single perspective. Of course, they can’t be appreciated from one single book/novel, either, and certainly not just from mine! However, the idea of multiple perspectives informs my book, and is another reason why I consider it a novel — the three perspectives making one picture (of many). It was important to me that I cover both the Third Reich period and the present day in the book. It was also important that the characters and their stories should not be intertwined. By keeping the characters, stories and periods distinct, I wanted to give the book scope. Many thousands and millions of people in Germany were involved in Nazism, in however small a capacity. I wanted to give the reader a sense of how far the Third Reich reached, and how the repercussions of this period are still felt (and avoided) today.

Q: Helmut’s story takes place before and during the war; Lore’s story immediately after the war; and Micha’s story generations after the war. Besides their particular time and experience, what do each of the three characters symbolize?

A: Three different, but interrelated perspectives on Nazism.

Broadly speaking, the first section deals with issues of identity and belonging. Helmut wants to be part of the Nazi world, but can’t be. The second part concerns itself with innocence and awareness. Lore took the Nazi ideology for granted and is confronted with the crimes committed (by members of her family) in its name. The last section deals with the continued repercussions of the war and Holocaust on the present day, and tackles the problems of guilt and closure through Micha’s painful investigation of his grandfather’s past.

In the run up to publication, I have been surprised by the number of people who have asked me (both in Germany and abroad) whether people in Germany “still” have not come to terms with the Holocaust/Third Reich. I, in turn, am surprised that this should be a question. Of course, there are many people who say that we should stop talking about it and move on. Of course sometimes you get exhausted. Of course Germany now has a multicultural population, and many of its current citizens have no immediate relationship to the period. But the idea that the question could or should have been dealt with by now is surprising to me. Fifty, sixty years is no time at all in comparison to the scale of the crime. Two, three generations. And each generation, each individual has to find their own perspective. And each individual’s perspective will change through the course of his/her life. I feel we/I have hardly scratched the surface: so little is known of what happened to the Roma, for example, and not nearly enough has been done to investigate the perpetrators” experiences.

Micha especially symbolizes the questions which will not go away. It is a difficult area: Holocaust fatigue is dangerous. I hope my book does not tire the reader.

Q: Lore of Part II is one of the strongest, most memorable characters of the novel. How old is she when she travels across the breadth of Germany, from Bavaria to Hamburg, with her four siblings?

A: Fourteen. In my head. But if readers think she is thirteen, thirteen and a half, fifteen, doesn’t really matter to me.

Q: Lore’s age is just one of the many questions left unanswered in the novel. What happens to Helmut’s parents? Was Gladigau Jewish? What happens to Tomas after he leaves Hamburg? Why do you leave these hanging?

A: I’m afraid I am still going to leave those questions hanging! I’m not particularly fond of explanations — like lots of little dead ends in a story. I would like to let the reader find his or her own answers — I think the book has more life that way.

I have never been published before. It is very exciting to hear different people’s interpretations of the stories/characters. They can be surprising, puzzling, gratifying, irritating. I hadn’t anticipated this, and I really enjoy hearing how the stories I wrote take shape in readers” minds.

In terms of the period which the book concerns itself with:

I think it is important not to adopt an attitude of knowing everything — it is arrogant, and there is still so much left to be heard and said, and so much that we will never know. The generation which experienced and survived the period is dying, and for some members of that generation silence was the only course they were able or willing to take.

I can’t tell people what to think about the Third Reich or the Holocaust.

I can’t explain genocide, anti-Semitism, Facism.

I have written three small stories, from three specific viewpoints, and hope they raise wider questions. To take one of your questions as an example. Helmut doesn’t know what happens to Gladigau — he is just gone. If you, as a reader, ask yourself, was Gladigau Jewish? Then you have to ask yourself — if he was, then what happened to him? For me, answering those questions within the text is like finishing a process for the reader before it has even begun.

Q: What is next for Rachel Seiffert?

A: Who knows? Not me!