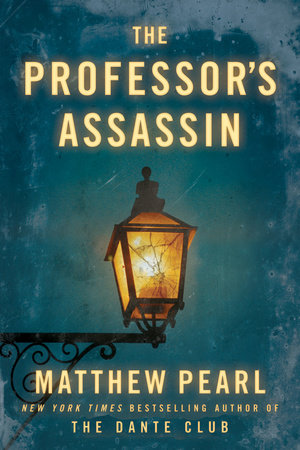

A Conversation with Matthew Pearl, author of THE DANTE CLUB

Q: Was there a historical Dante Club?

MP: Yes, and it was indeed centered around Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, America’s most revered poet of the 19th century. Longfellow had begun to translate Dante’s Divine Comedy as a way of coping with his wife’s tragic death. His friends and colleagues, many of whom Longfellow had inspired to read Dante, rallied around him. They called themselves the “Dante Club” and included poet and Harvard professor James Russell Lowell, author and editor Charles Eliot Norton, poet and publisher J. T. Fields, poet and Harvard medical professor Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, author and editor William Dean Howells, and Revolutionary War historian George Washington Greene. I couldn’t quite fit them all into the novel in a satisfactory way, however, and so Norton and Howells make only brief appearances. The members of the club would meet every Wednesday night at Longfellow’s house in Cambridge (which we can still visit!) to look over and critique Longfellow’s latest translations, and then adjourn for supper, often remaining until one or two in the morning. This somewhat informal group eventually inspired the formation of the Dante Society of America in 1881.

Q: What kind of research did you do to reconstruct the world of 1865 Boston?

MP: The central historical figures in the novel were writers — so lucky for me (or unlucky, depending on how you look at it) they wrote down everything. Letters, journals, notes, memoirs, I had endless entrances into their lives. I always find their comments about one another most intriguing and revealing, particularly when they’re critical about their friends. As for the rest of the world of 1865, everything helps. Historical maps, contemporary accounts of daily life, newspaper articles. When you’re writing historical fiction, you want to know what your characters would have had for breakfast, what kind of hats they would wear, how they might greet each other if meeting on the street.

Q: The novel is historical fiction. The historical circumstances of 1865 Boston and post-Civil War literary circles are interspersed throughout. What are the fictional elements of the novel, and did it ever seem as though they were intruding on the historical elements?

MP: As a writer of historical fiction, I believe you don’t want to fictionalize gratuitously, you want the fictional aspects to prod and pressure the history into new and exciting reactions. In The Dante Club, a series of murders, modeled after the punishments in Dante’s Inferno, disrupt life in Boston and Cambridge. This outbreak is the primary fiction of the novel, in addition, obviously, to the challenge it presents to the members of the Dante Club to react. However, I see this as very organic to the material. Dante, after all, designed his story as one in which a poet (that is, Dante himself), not a soldier or warrior, must descend into the bleak and horrifying terrain of Hell as the first step toward growth and redemption. I wanted to arrange a parallel descent for the Dante Club, to force them to confront the abyss present in their own day and society. Which really brings the fiction back to history: directly after the Civil War, crime and murder rapidly increased in American cities. So while the Dante murders are fictional, they reflect a very real, new sense of violence that had to be confronted at all levels of American culture.

Another example of fiction in the novel is the character of Nicholas Rey, the first African-American policeman in Boston. Although he is fictional, his situation comes from my research into the historical circumstances of early non-white police in the 19th century. I make a distinction between “accurate” and “authentic” when writing. Even when I’m not accurate, that is factual, I always try to be authentic.

Q: One review said the novel’s murders are gruesome enough to make Stephen King flinch. Is that true?

MP: I don’t think they’re quite that bloody! Part of what’s gripping about violence in narrative is that it often harbors secrets. Indeed, Dante’s Inferno is brimming with secret lives (and deaths) of its characters. The Dante murders jolt the Dante Club out of their steady and safe literary careers. As James Russell Lowell remarks in the novel, while they were translating Dante into ink, someone else translates Dante into blood. The violence is a signal of the power of literature — of the way in which literature can escape our control. Personally, I’m not a violent person at all. I’m a vegetarian! But if you see Stephen King, please give him a copy of the book and ask him what he thinks.

Q: Does a reader have to be familiar with Dante to enjoy The Dante Club?

Absolutely not! There are no prerequisites for the novel. I worked very hard with the goal of creating an engrossing story, whether or not you’ve ever read Dante or ever will. That said, I’m always excited to hear that the novel does end up making some readers want to read (or reread) Dante, or to rediscover Longfellow and his poetic peers of the 19th century. The characters in the novel are driven by a passion in literature, and so if the novel itself helps foster that passion in someone else, that’s an added bonus.

Q: You wrote the first draft of the novel while at Yale Law School, and then worked full time on the novel after receiving your law degree in 2000. Do you plan on practicing law?

MP: I was fortunate that Yale has a very open and creative law school. I took many courses outside the law school and every semester the students had a literature reading group. I was asked to lead one on “Dante and the Concept of Justice” and it was around that time that I began writing the novel. Being a law student meant constantly thinking about justice and punishment, in relation to the legal system and outside of it. This intersected with my literary interests in Dante, and I think both threads can be seen in The Dante Club. Although I don’t plan to practice law, I don’t feel I’ve left it completely behind. Recently, I wrote an article for Legal Affairs magazine on “Dante and the Death Penalty,” discussing how Dante’s use of justice sheds light on our debates about capital punishment.

Q: Although the events take place in 1865, the issues within the book feel very topical. Do you see a relation between the story of The Dante Club and any current trends or events?

MP: Definitely. Whether it’s the Columbine massacre or the assassination of John Lennon, we’re constantly asking ourselves whether art (literature, music, movies) can influence people to commit violence. And if so, then what? Do we prohibit that work of art? That’s a question the Dante Club must ask themselves. We have to ask ourselves how our communities can become healthier readers and audience members.

Q: Alexa.com recently listed The Dante Club as the number one bestselling book for reading groups. Is there something specific about the novel that would appeal to book clubs?

MP: I like to think of the novel as, in a way, being about a book club. The Dante Club was one of America’s most important book clubs, as their Wednesday night meetings ultimately led to our country’s first exposure to Dante’s poetry on a wide scale. There’s a remarkable power about reading together, reading collectively, that’s brought out by reading groups.

Q: What has been surprising about your experience of having the book published?

MP: Well, I’ve been contacted by some descendents of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Russell Lowell, two of the central figures who appear in the novel, expressing their delight at the novel and thanking me for bringing their ancestors to life. I lived with those characters for so long as part of my life it’s strange to actually hear from their families!

Q: With the release of The Dante Club, you have also helped reissue a new edition of Longfellow’s translation of Dante’s Inferno from Modern Library, for which you wrote a preface. How does Longfellow’s translation hold up these days?

MP: Longfellow’s translation is one of the most important, as it was the first translation of the Divine Comedy into English by an American. Since Longfellow was so famous, readers paid attention. The translation managed to introduce Dante to the country for the first time when it was published in 1867. Ironically, it did such a good job of inserting Dante into our culture, many translations followed and pushed Longfellow’s into obscurity. In fact, Longfellow’s translation had been out of print for over forty years until Modern Library reissued it alongside The Dante Club. Longfellow’s version is still one of the most accurate and faithful to Dante’s text. Pulitzer Prize winning poet James Merrill said he thought Longfellow’s was the best translation of Dante into English ever produced. I think it’s time to rediscover this remarkable product of America’s literary explorers!