Author Q&A

Del Rey: First of all, congratulations on winning the 2007 John W. Campbell Award for best new writer. It must have been an incredible experience not just to win but to be there in Japan to accept the honor.

Naomi Novik: It was amazing. Just the fact of getting nominated for the Campbell and the Hugo alone was fantastic, not to mention that it was a good excuse to go to Japan. You know, it’s a cliché that it’s an honor just to be nominated, but I profoundly felt that way. I was asked by an interviewer very early on, before His Majesty’s Dragon came out, which I would rather have: a New York Times bestseller or a Hugo Award. Well, I didn’t get a Hugo, but to me, the Campbell was just as much of an honor.

DR: And you didn’t do too badly with the Times, either. Your latest book, Empire of Ivory, debuted at #15 on the Times list, I believe.

NN: Those two things both matter deeply to me as an indication that people are reading my work and connecting with it. It’s extremely important to me as a writer that I feel I’m reaching people. I don’t need to be making a fortune, but I do want to feel that I’m not writing into the ether. And of course what it also means is the freedom to keep going. That’s the real reward, that I get to keep doing this.

DR: Empire of Ivory is the fourth book in the Temeraire series. Are you planning a definite conclusion for the series, or is it open-ended? And how far ahead do you plot things out?

NN: I definitely know in detail what’s going to be happening a couple of books ahead of where I am. And then I have a general game plan where I know that the books end with the end of the Napoleonic wars, and the series has a definite arc to it.

DR: What year are we in now?

NN: Empire ends in August of 1807.

DR: You’re not very explicit about exact dates in the books. Readers sort of have to infer what year it is by their own knowledge of history.

NN: Yes, I have a timeline myself, and you can pin things down pretty well by the placement of historical events like Trafalgar. But I generally don’t want to nail things down too strongly. For one thing, travel in this time period was very different. A sea journey, the same journey, might take four months or eight months, depending on what time of year you did it, what kind of weather you ran into, what kind of ship you were on, whether you just had bad luck. And it was very much subject to the vagaries of the wind and the sea, and so I actually take the liberty of letting journeys sometimes take however much time is best for my story, my narrative, because I am aiming for an historical affect.

DR: But of course you’ve introduced another means of travel that’s a lot faster than anything historically available.

NN: Right, although this is an interesting point that isn’t explicit in the books. Dragons don’t necessarily travel much faster than ships over long distances. Ships can make, you know, twenty miles an hour under the right circumstances. I’ve pinned the speed of dragons to the speed of pterodactyls, about thirty miles an hour. And that’s what I feel a really good dragon could make. Some of the larger dragons, like the Regal Copper, have clearly been bred for massive size, and they have the endurance but not necessarily the ability to get up to that speed. So dragons fly at different speeds. Dragons are, of course, much faster than horses or anything else when it comes to flying straight over land, simply because they can go over obstacles. So it does change transportation a lot. But because dragons have not, at least in the West, been fully exploited for this quality before the time of my books, it hasn’t made the world shrink.

DR: Empire begins with a good example of the effect dragons can have on transportation, when Temeraire and other dragons are used to bring allied soldiers out of the besieged city of Danzig . . .

NN: Exactly. At the end of Book 3, Black Powder War, the dragons are used to carry the garrison off. And it’s also in Book 3 that Napoleon really starts to take advantage of the speed and mobility of dragons to move his army much faster than before—and his army was already, historically, much faster than any of his opponents. Once Lien, the dragon introduced in Throne of Jade, has come to France, bringing with her the knowledge of Chinese dragon technology—not in the Western sense exactly, not mechanical technology, but the efficient methods the Chinese have developed to incorporate dragons into their society, which are far in advance of anything developed so far in the West—once this happens, Napoleon is very quick to grasp the advantages. And of course he possesses the power to simply impose drastic changes in the use and treatment of dragons, which in a Parliamentary system like England’s simply isn’t there. That’s what’s happening in Book 3, and that’s why the events I’m writing about start to veer off a lot more from the historical record. The advances from China are hitting the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, and it’s creating a kind of perfect storm, which at the moment is making Napoleon even more dangerous and overpowering than he was already.

DR: The existence of dragons is the main point at which your fictional 19th century departs from history, but there are also more subtle differences, most of which seem directly or indirectly attributable to the presence of dragons. The survival of Nelson post-Trafalgar seems worth mentioning in this regard. The impression is that there is no detail, however small, that you’ve overlooked in fleshing out your alternate world.

NN: Well, thank you. It’s one advantage of working with history that I have this fully fleshed-out, realistic world pre-made for me at the price of cracking a book or going online. And then what I generally try to do, if I feel like I see a departure from history, my first step is always to know what really happened in a given stretch of time or in the course of a particular event. Once I know what really happened, I think about how dragons would have affected it. I feel very strongly that for me, the point of departure really is that there are dragons. That’s it. Every other difference has to come out of that fundamental one. That’s the fun, what-if puzzle of the whole thing. And that constraint, I think for me, is a useful one. I like having that kind of restriction.

DR: It must be tempting to go beyond that though, sometimes.

NN: Of course. Sometimes I run into something from history that I’d like to change, because it’s inconvenient to my story, but I can’t see how do it and stay true to everything else that’s changed. So I force myself to work around it. Usually I find that I come up with some kind of third twisting solution that is more interesting than what I originally wanted to do.

DR: Each novel in the series has its own plot and thrust, but there are also grander plots, or themes if you will, that move through and beyond each book, giving the series as a whole a kind of symphonic aspect. Two I’d like to focus on, and they are closely related, are feminism and slavery. Again, as with the departures from history referred to above, these themes are bound up with dragons. Can you talk a bit about these two themes, and this aspect of your work?

NN: These are issues that confront every historical writer of this period. Anybody who enjoys this period and likes it has to deal with the fact that this was not a great place to be anybody other than a rich white guy. Not even just a white guy. You had to be rich, because class is also a major issue, although that’s one that I’ve dealt with somewhat less so far. I think one solution that writers do is to modernize. So that if you read a lot of Regency romances, for example, very frequently the characters are basically all modern in their attitudes. And I felt very strongly that was not the way I wanted to go. To me, that breaks the suspension of disbelief and the sense of world building. So then, all right, I have a situation where the world is a pretty sexist, racist, classist place, and for myself as a reader, what matters to me is that I don’t get the feeling that the author is sort of glorifying the sexism, racism, or classism of the characters. That if there are things that are bad, the author deals with them and responds to them. And for myself, to enjoy writing in this period, that’s one of the reasons why I love the idea of doing alternate history and using dragons as sort of a focal tool. Because it let me—in a way that I felt made sense, that didn’t break the sense of the world—it let me sort of fix some of this stuff.

DR: Not by waving a magic wand, but in a rational way that has its own logical development.

NN: Yes. I’m still writing in a world that has all these problems, but I like to feel as though I’m giving the reader and myself a sense of being able to see how this world developed. Addressing these issues or themes is something that really matters a lot to me. I believe you have to tell a good story first, and you have to have characters that you love, but also who are true to their time and place.

DR: Like Captain Will Laurence.

NN: Laurence is a guy who grew up within exactly this historical world, with all its problems, and without even having to think about the issues of his privilege or anything like that, without ever having to think of women as potentially his equals. I mean, certainly Laurence thinks of women as human beings, but always as a different class of humans. It would never have occurred to him that a woman could be a soldier. But despite all that, he remains open minded. I think fairness is kind of the keystone of his character. He tries very hard to do what is fair and what is right. I think that the Laurence of His Majesty’s Dragon will not recognize the Laurence of the last book, and yet it will still be the same guy. He’s being forced to change in some ways, in ways that are uncomfortable for him, and yet I think he’s dealing with it all in an honorable way.

DR: I know intelligence varies among dragon species, but are the smartest dragons any smarter than humans? Temeraire, for example, seems able to more than hold his own with human mathematicians, and there’s a delightful scene in Empire of Ivory where he and some other dragons devise a non-Euclidean geometry as a kind of game . . .

NN: Dragons have a slightly different intelligence than humans. That’s why non-Euclidean geometry comes much more naturally to them. Dragons probably have more capability in terms of spatial relations. But I would I say that there’s a range of dragon intelligence just like there’s a range of human intelligence. The two species have very different kinds of intelligence, and they think in different ways.

DR: Given the intellectual abilities of dragons, why haven’t they developed their own civilizations? It seems that their highest intellectual and social accomplishments depend upon human influence and impression. Without humans, they remain wild, feral creatures of varying intelligence—or so it seems thus far.

NN: That’s not quite the case, although I can’t answer this question fully without giving away some spoilers for Empire of Ivory and books still to come. But in Empire, for example, there is an African culture that’s very much a human/dragon cooperation, and there will be some very interesting developments when we get to Peru and the Incan civilization. And Arkady and the ferals that were first encountered in Black Powder and continue to play an important part in Empire have their own society. The difficulty for dragons is that they don’t have hands, to put it bluntly. They don’t have opposable thumbs. So that’s a limitation right there on the kind of things they can build for themselves, the kind of tangible artifacts that can go along with a sophisticated culture but aren’t absolutely necessary for it. The other thing is, dragons are by and large more laid back than humans. The evolutionary pressures on them have been quite different. Their preoccupations are very different from those of human beings. They care about their territories, about treasure, about their eggs. Actually, their love of treasure is I think an outgrowth of the valuation they put on eggs. In fact, treasure is one of the main ways that dragons negotiate with each other to establish the relationship bonds that can lead to an egg. Some of this behavior I based on birds, such as the bower bird, which spends an inordinate amount of time building an elaborate, highly decorated nest in order to attract a mate. Because dragons don’t really need to be afraid, except of other dragons. I don’t think that they’re as inclined to make war on each other. They’re very aggressive, obviously, and not at all shy about fighting, but there are fewer of them than humans, and therefore more space for every dragon to establish a territory. So there are all these reasons why they don’t create a massive society on their own, without some relationship with people.

DR: What about religions? Human religions don’t seem to hold much interest for dragons, though some of them seem fascinated by philosophy. Do dragons have their own religion or religions, or are they fundamentally lacking in whatever it is that causes humans to experience a religious dimension to existence?

NN: I think there are dragons who are religious. We have a glimpse briefly in Black Powder War of dragons praying in a mosque. One determinant of how religious people are is whether or not they were raised in a religious environment, and I think the same is true to a degree of dragons. Fewer dragons than people are brought up in a religious environment, so there are fewer religious dragons.

DR: But they themselves haven’t developed their own god idea: I mean a dragon god or gods.

NN: This is another one of those areas where I’m afraid of giving away some spoilers, but I can say that religion is an issue that will be addressed more in upcoming books. But I think it varies from dragon to dragon. Temeraire is very intellectual about all this, and doesn’t quite get it. I think Temeraire would be perfectly willing to believe God existed, but he’d spend all his time asking uncomfortable questions about, if God does exist, why does He allow certain things to happen.

DR: You’ve mentioned that Temeraire and Laurence will visit Peru. What about the rest of South and North America and the indigenous civilizations there, the Maya, the Aztecs, the North American tribes?

NN: Again, trying to steer clear of spoilers, one reason the European contact with the Americas had such catastrophic effects on the native population was the introduction of new diseases. That will still be a factor in my books, though the presence of dragons will change things in, I hope, interesting ways. But just like we talked about earlier with slavery and so on, my interest isn’t in taking ugly incidents in the past and making them go away. Dragons are the focal point of the changes I’ve introduced into history, but they’re not a panacea for all the ills of the past. It doesn’t erase the fact that all these people were conquered and killed. For instance, there has been some colonization in my books. The Portuguese do have Brazil.

DR: Ignoring those kinds of facts can make alternate history almost immoral, can’t it?

NN: I believe pretty strongly that anything you do as a writer of alternate history, as long as you do it with respect and thoughtfulness, it’s not wrong. For myself, it’s not something I want to ignore. It is the story I’m telling. I support everybody’s right to tell the story they want to tell. If somebody wants to write a Regency romance where the characters are all modernized and speak in contemporary idioms, that’s fine, as long as you’re not trying to put it over as an authentic representation of history. But in this case, I thought that it might be immoral for me to ignore these elements, of slavery and so on, because, first, that’s very much the story I’m trying to tell, and second, it violates my cardinal rule, which is that all the changes have to be tied to dragons. The dragons of the new world couldn’t protect the people of the new world against the introduction of diseases to which they had no resistance. On the other hand, I do have the freedom to ask what would happen if the dragons of the new world had a similar effect upon the dragons of the old world . . .

DR: The Temeraire books are billed as fantasies, primarily because of the dragons, and the alternate history aspect, but they seem a far cry from traditional fantasies. There’s no magic, after all, and the abilities of the dragons are given a scientific veneer, and obviously you have a great respect for history . . .

NN: My general feeling is that when you’re writing fantasy, it’s best not to ask readers to swallow twelve things at once. By narrowing focus, you make it easier for the reader to suspend disbelief and believe that what they are reading is real, assuming that’s the kind of feeling you want in your readers, and sometimes it’s not. For instance, I would point toward Patricia McKillip’s fantasies, which are much more about evoking an atmosphere and a mood and a sort of sense of wonder.

DR: There’s a dreamlike logic driving her books. They’re like fairy tales from an alternate world.

NN: Exactly. She’s not trying for realist effects. In the Temeraire books, I am trying for those effects. If you’re writing realist fantasy, I think it’s best to put yourself on a diet as a writer, you know, where I’ll ask my reader to swallow this one thing, and as long as they accept it, then everything else is going to make sense to them in what they know of history, what they know of the real world, what they know about how people relate to each other. That’s what I think is important for realist fantasy, where you’re trying to convince your reader that it would have happened this way, if only. As for the dragons, I certainly haven’t tried to apply any kind of rigorous science to them. I suspect in many ways they are implausible. But there is enough science, or pseudo-science, that I feel the reader can buy it on those terms.

DR: What about the movie? Can you bring us up to date on what’s been going on since Peter Jackson optioned the film rights for His Majesty’s Dragon?

NN: I really don’t know what’s going on with that. These things can go on for years and years. You sort of knock on wood and hope that it happens at some point, but it’s really out of my hands. The wonderful thing is, Peter Jackson is definitely the right person to make the movie, when and if one gets made.

DR: Has all your research into and imaginative immersion in the Napoleonic period affected your perspective on our own time, and the War on Terror in particular?

NN: One thing I’ve come to appreciate more and more in writing these books is that when it comes to war, once certain things are set in motion, we really don’t have any idea where they are going to end up. Even Napoleon, a military genius, won a lot of his battles by luck. At the battle of Jena-Auerstedt, for example, in Prussia, he badly misjudged where the main body of the Prussian army was, and about a quarter of his army ended up facing three-quarters of the enemy’s army, while he faced and beat the remaining quarter. Despite all his planning, the battle came down to the luck of the draw. You can’t delude yourself into thinking that you have control, and you have to be careful about going into these things with an illusion of how much you can accomplish with military force. Even if you have more money and more weapons and more men, there’s no such thing as a sure thing. At the same time, my research has given me a lot more sympathy for the people on the ground and the people who are trying to carry out the larger strategy.

DR: You do your writing in libraries. Why?

NN: It’s not specifically libraries. I’m constantly on the hunt for places where I can park myself with a laptop in a pleasant environment that’s not too loud and has no Internet.

DR: Is that key? No Internet?

NN: Yeah, I can’t be trusted with Internet. In fact, one of the dangers for a lot of writers is the danger of doing too much research to begin with, and you end up researching and researching and researching, and you don’t write your damn story. With an Internet connection, it’s very easy to end up spending an entire day researching the choice of one word.

DR: Of course, working in a library doesn’t exactly remove that difficulty.

NN: Well, I like to do my research online. So I save that for home.

DR: But don’t you find that working in libraries has its own distractions?

NN: I also like to work in museums, like the Metropolitan Museum. People are pretty quiet in a library, so in some respects it’s better than a café, although cafés have their advantages. But I have noise-canceling headphones that I originally got for use on airplanes, and they work great. So in a practical way, I’m not really distracted by my surroundings. I have my classical music playing . . .

DR: You listen to music while you write?

NN: Yeah.

DR: Do you play music from the time period in which your books are set?

NN: Yes, I make a new playlist for each book. For Empire of Ivory, I got a whole lot of African music.

DR: Do you play the same songs over and over?

NN: My playlist usually runs to about 100 songs or so, so I don’t really notice any repetition. And once I start writing, the music very quickly fades into the background. It’s really there just to drown out anything around me.

DR: It’s all instrumental stuff.

NN: Instrumental and foreign language stuff—languages that I don’t speak, so I don’t get distracted by the lyrics.

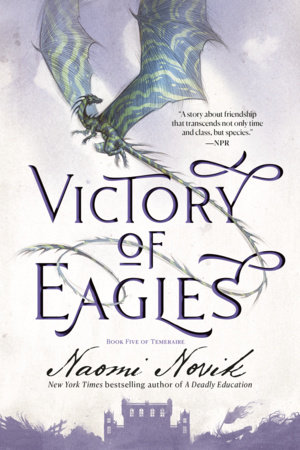

DR: When is the next volume of Temeraire going to be published?

NN: July 2008.

DR: Do you have a title yet?

NN: Victory of Eagles.

DR: Do you have any plans to explore the past of Temeraire’s world in greater detail, say in short stories or other novels, for example?

NN: I do, actually. I actually have a short story in progress where Marc Antony is the first man to tame a dragon in the West. He doesn’t set out to do it; it’s more of a drunken accident. I’m really looking forward to finishing it. And I definitely want to explore more of the world, the universe. But the problem is time. There are so many other things that I also want to explore. After Victory of Eagles is done, in about another month, I’m going to be taking some time before starting Book 6, because the Temeraire books are moving to a once-a-year schedule, so I’ll have a full year between, which should be enough time for me write one other novel, something completely different, and I want to get into that habit, sort of switching back and forth between projects.

DR: It sounds like you’ve already got something in mind.

NN: I have two concepts, two ideas where I’ve already written pieces.

DR: Both ongoing series like Temeraire, or stand-alones?

NN: One is a five-book cycle, and the other I’m not sure.

DR: Both alternate histories?

NN: It’s hard to say. One is a time-travel story, and as soon as you’ve got time travel, then history becomes a sort of fluid concept. And the other one is set five minutes in the future: a science-fictional story. They’re alternate histories in that they’re set in our world. And I do like to use our world and our history as a foundation, but they aren’t alternate history necessarily in the same sense of the Temeraire universe, where I’m really following an historical narrative, the Napoleonic wars.