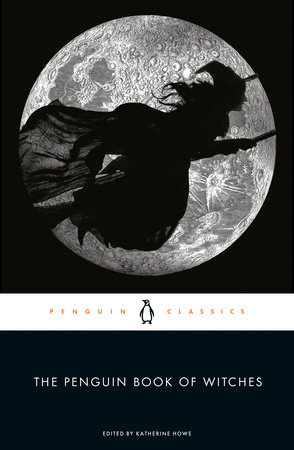

Award-winning historian Mary Beth Norton reexamines the Salem witch trials in this startlingly original, meticulously researched, and utterly riveting study.

In 1692 the people of Massachusetts were living in fear, and not solely of satanic afflictions. Horrifyingly violent Indian attacks had all but emptied the northern frontier of settlers, and many traumatized refugees—including the main accusers of witches—had fled to communities like Salem. Meanwhile the colony’s leaders, defensive about their own failure to protect the frontier, pondered how God’s people could be suffering at the hands of savages. Struck by the similarities between what the refugees had witnessed and what the witchcraft “victims” described, many were quick to see a vast conspiracy of the Devil (in league with the French and the Indians) threatening New England on all sides. By providing this essential context to the famous events, and by casting her net well beyond the borders of Salem itself, Norton sheds new light on one of the most perplexing and fascinating periods in our history.