READERS GUIDE

My father-in-law was a pilot. During World War II, he was shot down in a B-17 over Belgium. With the help of the French

Resistance, he made his way through Occupied France and back to his base in England. Ordinary citizens hid him in their homes, fed him, disguised him, and sheltered him from the Germans. Many families willingly hid Allied aviators, knowing the risks: They would have been shot or sent to a concentration camp if they were discovered by the Germans.

In 1987 the town in Belgium honored the crew by erecting a memorial at the crash site, where one of the ten crew members died. The surviving crew was invited for three days of festivities, including a flyover by the Belgian Air Force. More than three thou- sand Allied airmen were rescued during the war, and an extraor- dinarily deep bond between them and their European helpers endures even now.

My father-in-law, Barney Rawlings, spent a couple of months hiding out in France in 1944, frantically memorizing a few French words to pass himself off as a Frenchman, but his ordeal had not inspired in me any fiction until I started taking a French class. Suddenly, the language was transporting me back in time and across the ocean, as I tried to imagine a tall, out-of-place American struggling to say

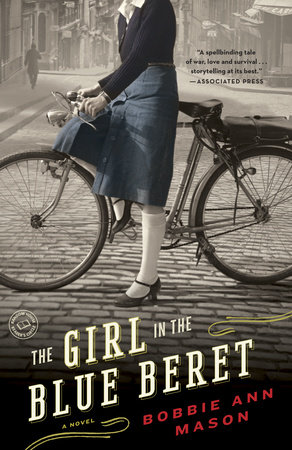

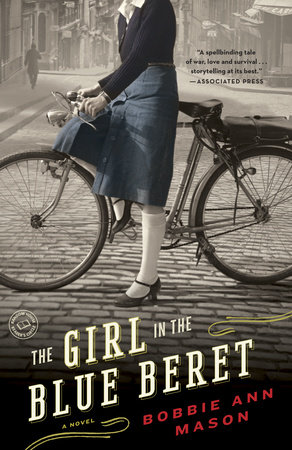

Bonjour. Barney had a vague memory of a girl who had escorted him in Paris in 1944. He remembered that her signal was something blue—a scarf, maybe, or a beret. The notion of a girl in a blue beret seized me, and I was off.

I had my title, but I didn’t know what my story would be. I had to go to France to imagine the country in wartime. What would I have done in such circumstances of fear, deprivation, and un- certainty? What if my pilot character returns decades later to search for the people who had helped him escape?

Writing a novel about World War II and the French Resistance was a challenge both sobering and thrilling. I read many riveting escape-and-evade accounts of airmen and of the Resistance net- works organized to hide them and then send them on grueling treks across the Pyrenees to safety. But it was the people I met in France and Belgium who made the period come alive for me. They had lived it.

In Belgium, I was entertained lavishly by the people who had honored the B-17 crew with the memorial, including by some of the locals who had witnessed the crash landing. I was overwhelmed by their generosity. They welcomed me with an extravagant three- cheek kiss, but one ninety-year-old man, Fernand Fontesse, who had been in the Resistance and had been a POW, planted his kiss squarely on my lips.

In a small town north of Paris I met Jean Hallade. He had been only fifteen when Second Lieutenant Rawlings was hidden in a nearby house. Jean took a picture of Barney in a French beret, a photo to be used for the fake ID card he would need as he traveled through France over the next few months, disguised as a French cabinetmaker. And in Paris I became friends with lovely, indomitable Michèle Agniel, who had been a girl guide in the Resistance. Her family aided fifty Allied aviators, including Barney Rawlings. She takes her scrapbooks from the war years to schools to show children what once happened. “This happened

here,” she says. “Here is a ration card. This is a swastika.” She pauses. “Never again,” she says. The characters in

The Girl in the Blue Beret are not portraits of actual people, but the situations were inspired by very real individuals whom I regard as heroes.

Questions and Topics for Discussion

1. Discuss the special bond between Allied aviators and their European helpers. Why did it take so long for many of them to re- unite after the war?

2. What does flying mean to Marshall? Discuss Marshall’s failed B-17 mission and the effect it had on his life.

3. Re-read and discuss the images of flight throughout the novel. How does the final sentence tie in with these?

4. What is Marshall’s feeling about the young man he remem- bers as Robert? Does Marshall romanticize him? Why is finding Robert so important to Marshall?

5. Love and war. There are two main love stories in this novel—the younger couple, Annette and Robert, and the mature couple, Annette and Marshall. How are these relationships differ- ent from each other? What does war do to love and romance?

6. Why is Marshall so unprepared for what Annette reveals to him? How does he deal with her story? What possibilities lie ahead for him?

7. The name Annette Vallon is inspired by a historical figure, a woman who was William Wordsworth’s lover during the French Revolution and the mother of his illegitimate child. What sugges- tions are being made by the use of the name here? What else can you learn about Annette Vallon from further research?

8. What do you make of the epigraph by William Words- worth? Is it appropriate? How does it connect with the use of Annette Vallon’s name?

9. What do mountains mean to Marshall? Trace the impor- tance of mountains at different stages of his life.

10. How does Marshall look back on his war experience? How does his perspective change during the course of the novel?

11. How do the experiences in the book compare with your own experiences of war? Have you ever known anyone captured during wartime?

12. What is meant by second chances in the context of this book?

13. How do you interpret the ending? Review the emotional developments that lead up to the last lines, especially Marshall’s thinking as he falls to sleep the night before. Based on your under- standing of the characters and their situation, what do you imagine they are likely to do next? How does the aviation term, “gaining altitude,” apply here?